The murders of nine black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, last week put a bright spotlight on white supremacists who use the Internet to organize, proselytize, and radicalize—a process that ended in bloodshed when 21-year-old Dylann Roof allegedly went on a killing spree motivated by racism.

The massacre has returned scrutiny to white supremacist communities online—attention their members have long attempted to avoid.

The entire world looks at the Internet more wearily since Edward Snowden revealed the National Security Agency’s vast online surveillance operations in 2013. Privacy tools have spiked in popularity across the board. White supremacists—who often feel targeted and persecuted for their race—are even more on guard.

Even before Snowden, many supremacists took extra care to use powerful privacy tools to maintain anonymity online and to protect both the confidentiality and integrity of their communications over the Internet.

In this respect, white supremacists have a lot in common with violent Muslim jihadists who have turned to many of the exact same tools to avoid scrutiny as they take advantage of the Internet to recruit new radicals to their respective causes. Of course, these tools are increasingly popular with millions of people around the world—not just criminals, terrorists, and hate mongers—from human rights advocates to soldiers to average Web surfers looking for security.

In the 19th century, the Ku Klux Klan met with elaborate ceremony in secret to discuss the “purification” of America. Today, supremacists from all over the world meet online, and they use strong security tools to effectively spread their message but stay out sight as best they can.

Supremacist paranoia isn’t entirely without merit. Participation in sites like Stormfront, known as the digital home of white nationalism for over two decades, has resulted in political scandal in the U.S., as well as arrests in the Netherlands and Italy.

On Stormfront, records show discussion of the Tor anonymity network stretching back to 2004, just after the software hit the public. But as with mainstream security-conscious users, white supremacists aren’t always sure about Tor, which was originally developed by the U.S. military. The government funding and successful police investigations into Tor users cast doubt for many supremacists, plus they believe the investors and developers are part of the “ZOG machine,” an old anti-Semitic conspiracy theory (Zionist Occupied Government) that’s stretching well into the future.

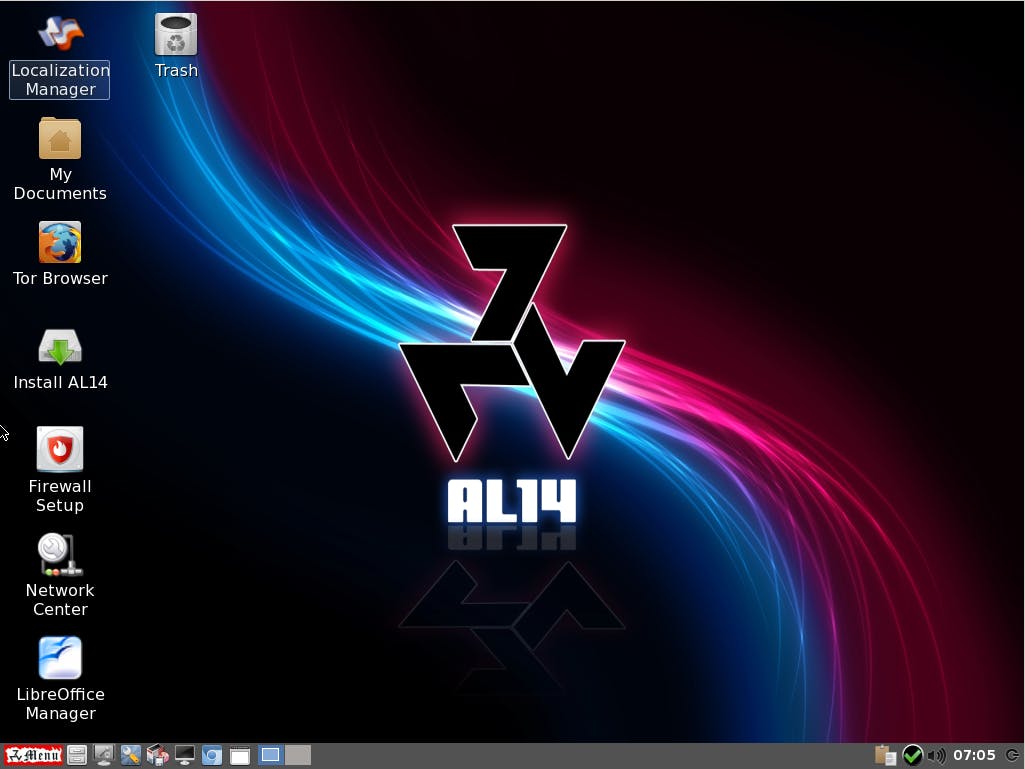

In 2011, two years before Snowden became a household name, white supremacists built “Apartheid,” a security-focused version of the Linux operating system meant “for proud whites” that came with Tor pre-installed in order to protect users’ identity and communications.

With Apartheid, the white supremacists showed they had something else in common with the jihadists they so despise: Both were profoundly bad at creating security software.

Jihadists’ attempts at writing encryption software have ended in embarrassing failures. In 2011, the same year Apartheid was created, the Global Islamic Media Front had to warn its users against downloading its own encryption program, “Mujahideen Secrets 2.0,” because it had been compromised.

Apartheid’s creators are either smarter or lazier than that, depending on your point of view. Instead of creating their own security and encryption programs from scratch, white supremacists included already popular programs like Tor.

In fact, the entire Apartheid operating system was a thinly veiled rip-off of another Linux distribution (PCLinuxOS) and added little of its own flavor beyond racist iconography and the inclusion of Tor.

Apartheid fell dormant years ago, however, and supremacists have since moved on to more mainstream tools.

As alternatives to Tor, supremacists use virtual private networks (VPN), I2p (Invisible Internet Project), and Freenet. VPNs are commercial products and the easiest to use but don’t do much to fully protect your anonymity from authorities.

On the other hand, I2P and Freenet can be more difficult to set up but are far more effective anonymizers. They’ve been used and recommended by some—but not many—supremacists for several years, especially after Snowden’s revelations.

Popular Linux distributions like Debian and Ubuntu are discussed by white supremacists as more secure alternatives to Windows and OS X. Tails, an even more secure and agile operating system, is often recommended as part of a heavy-duty security approach for the most cautious and paranoid supremacists.

Full disk encryption—the act of locking your computer down so absolutely no one can access its data without your permission—has been en vogue among security-conscious white supremacists for at least a decade.

Stormfront itself has taken steps to become a more secure website. Last year, owner and white nationalist icon Don Black installed HTTPS encryption on Stormfront.org to protect users from eavesdropping and phishing. The switch came after a push from users that had become increasingly wary of surfing the Web without encryption.

Since then, supremacist interest in Internet privacy has picked up dramatically.

That’s true of the entire population outside of the movement, but what makes supremacists unique is that in several parts of the world, merely discussing their political beliefs is illegal—because, lawmakers argue, those beliefs have a history of leading to horrific violence and oppression.

Many supremacists believe they’re engaged in conflict between races and governments and their own movement.

This perceived state of war makes for an even stronger attraction between Internet security and the white supremacist.

Photo via Paul Walsh/Flickr (CC BY SA 2.0) | Remix by Jason Reed