Life under the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) is supposed to be easier.

The government project aims to give employment of up to 100 days for Indians in far-flung and desolate areas of the country.

These men and women work at infrastructure project sites such as roadways, bridges, and tunnels; their attendance, payroll, and all other work-related information is processed only digitally.

But without notice—and through no fault of their own—they can suddenly be unable to log their hours or access their funds, their livelihoods stripped away for an hour, a day, a week, or months at a time.

That’s because the government, attempting to clamp down on dissent under the guise of preventing the spread of misinformation, has cut off their access to the internet.

For many Indians, an internet shutdown isn’t about being unable to post. It’s life or death.

A 35-year-old mother of five from the western Indian desert state of Rajasthan who only identified herself as H.K told Human Rights Watch (HRW) how her entire life is thrown out of gear when she loses access to the internet.

The Dalit (a historically oppressed group of people) woman said, “When the internet is shut down, I have no work, do not get paid, cannot withdraw any money from my account, and cannot even get food rations.”

HRW is one of the few international organizations keeping a close eye on internet shutdowns in India and their impact on the lives of some of the most marginalized people in the country.

Another Dalit mother and NREGA worker who identified only as N.P told HRW, “We travel far to reach our worksites, but have to go back home if the internet does not work. Entire families depend on NREGA for sustenance. How will we feed our children?”

According to Jayshree Bajoria, associate director at Human Rights Watch (HRW), “Internet shutdowns cause disproportionate harm to socially and economically marginalized communities who depend on the government’s social protection programs, including for the right to food and livelihood. The government’s Digital India mission has made the internet essential to access government programs and shutdowns kill people’s access to food rations, minimum work guarantee, or even e-governance solutions in rural areas.”

While the Aadhaar digital identification program was brought about by the Manmohan Singh-led United Progressive Alliance that preceded Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s regime, it has now become intertwined with his Digital India campaign, a push to supercharge connectivity across the country.

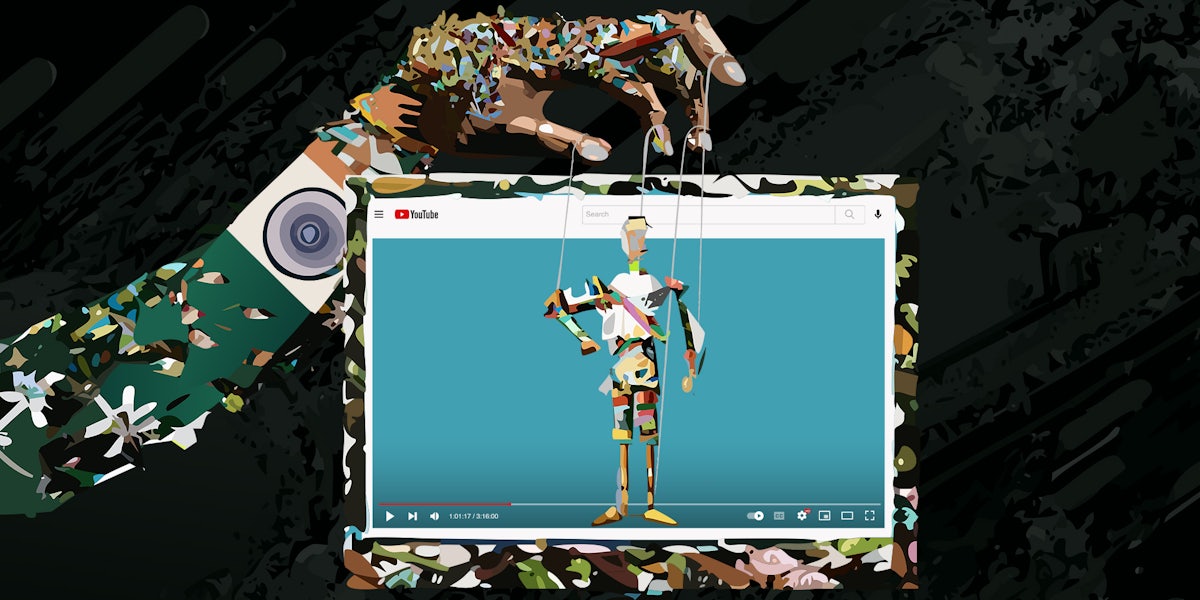

And as the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) asserts ever more control over the nation, having your entire life online means the party has total power to grind it to a halt in an instant.

According to InternetShutdowns.in, a website that tracks internet shutdowns in India, Rajasthan alone has experienced a whopping 98 internet shutdowns since 2012, second only to the Jammu and Kashmir region’s 422 internet shutdowns.

The reasons range from the shocking to the mundane. In June 2022, the internet was shut down in Rajasthan to control the spread of rumors and potential outbreaks of violence, like after the beheading of tailor Kanhaiya Lal.

However, there have been cases where internet access is cut off just to prevent students from cheating during exams.

The timing can be fickle and unexpected, and whether it does anything other than exacerbate hardship is unclear.

In Manipur, a state in the northeast of the country, a 78-day shutdown was implemented in the wake of violence between two tribal groups.

The effort clamped down discussion and news about the incidents, but it also hid a horrific act of violence from escaping the confines of the rural, remote state.

Just a day after web access was blocked at the onset of the violence on May 4, two women were forced to strip, paraded around naked, and sexually assaulted by a mob.

All of this was caught on a mobile phone camera.

Because of the shutdown, the incident only came to light on July 19. After services in the area were restored temporarily, the video promptly went viral on X.

India has emerged as the internet shutdown capital of the world, scoring the top rank for five years in a row, becoming Modi and BJP’s favorite quick-fix method to prevent or control an outbreak of communal or ethnic violence fueled by rampant Islamophobia, majoritarianism, and othering of minorities.

It’s all part of a concerted effort by the party to exercise as much influence as possible over every single digital space in the nation.

The government says it shuts down the internet to prevent the spread of fake news and rumors, and in turn, stem the spread of violence.

It is not hard to point to incidents of violence that precipitate a severe crackdown on access to digital services.

But it can also allow the government to turn a blind eye to the same violence.

Three months passed before Modi, seemingly compelled by the leak of the shocking video, broke his silence on the violence between Meiteis and Kukis in Manipur.

In his speech, Modi condemned the assault and claimed peace was coming to the region.

He did not address the internet shutdown.

A local official, however, did so in a charged interview with India Today. On July 20, Manipur Chief Minister Biren Singh was pressed about the incident.

“How did you not know about this until now?” the anchor asked about the assault. “The incident is from May 4, a police report was filed on May 18?”

“There are hundreds of similar cases that are happening here. That’s why internet is banned in Manipur right now,” Singh responded, a stunning admission by a government official that the shutdown was to keep information under wraps.

The opposition party jumped on the comments.

“77 days since the ghastly incident where two women were stripped, paraded and allegedly raped,” wrote Indian National Congress member Jairam Ramesh. “The rest of India had little clue that such a horrific incident occurred due to the ongoing internet ban in Manipur … When will the Modi government stop acting like all is well?”

Because it’s not just Manipur that’s impacted.

While the internet was cut off there, the shutdown prevented access to any information and videos, staving off the kind of protest against hate crimes and violence that have broken out in other parts of the country.

“Had there been internet access, accounts of abuses such as violence against women captured on that video would likely be reported quicker and the authorities would be under pressure to investigate promptly,” Bajoria said.

The Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF), which has tracked shutdowns across the country, says the motivation is clear.

“Given the immense social and economic impact that internet shutdowns have, which have been measured and documented and made available to state authorities on several occasions by researchers, scholars and advocates, the frequency of internet shutdowns seen in India reveals either a direct intent to prevent the truth about ground realities from coming out, or at the very least a reckless disregard for the freedom of expression of the voices that inhabit the impacted areas,” said Tanmay Singh, senior litigation counsel for IFF.

Like a number of digital crackdowns by the Modi government, they walk the very fine line between legal and illegal.

Procedures for an internet shutdown were established in the Telecom Suspension Rule, 2017 and clarified by the Indian Supreme Court in Anuradha Bhasin v. Union of India.

This seminal case was brought by Indian journalist Anuradha Bhasin, the executive editor of Kashmir Times, who filed a petition before the court after her publication faced tremendous hurdles while reporting on ground realities in Kashmir during the infamous internet shutdown that lasted over 18 months.

The internet was shut down in the region in August 2019, when the Indian government scrapped special provisions and autonomy granted to the state of Jammu and Kashmir. The region was reconstituted into two Union territories administered by the Indian government.

In response to Bhasin’s petition, the court ruled that “an order suspending internet services indefinitely is impermissible … Suspension can be utilized for temporary duration only.”

The court further said, “Any order suspending internet issued … must adhere to the principle of proportionality and must not extend beyond necessary duration,” calling into question the rationale behind long-term internet shutdowns but not outright preventing the government from implementing them in circumstances where public safety or national security are compromised.

Depending on exactly what is shut down and for how long, the impact can be different for different people.

India’s capital city New Delhi has been hit by several shutdowns during protests.

On Jan 26, 2021, violence broke out after farmers—who had been congregating at Delhi’s borders for months protesting new agriculture-related laws—held a tractor rally and drove into the city on India’s Republic Day.

In response, the internet was suspended for approximately four to 24 hours in different parts of Delhi and its bordering areas in Western Uttar Pradesh.

In some areas, the shutdowns were extended after the initial orders expired.

All told, over 50 million people lost access.

In Rajasthan, it was the rural poor who were impacted, while in Dehli, the impact was felt by India’s urban middle class, who have grown increasingly dependent on mobile phone apps for meeting day-to-day needs.

These abrupt shutdowns effectively thrust a bustling digitally savvy population population into a complete communications blackout that halted their lives for a day.

That may seem trivial, but it has real impacts on the safety of citizens.

As Modi pushed a demonetization campaign and made an appeal to go “cashless,” encouraging Indians to adopt digital payment options in favor of currency, many are unable to purchase anything during the course of a shutdown.

Meanwhile, women who work outside their homes in New Delhi often use apps for booking taxis. Some even share Ubers to travel safely to and from their workplace.

Safety is a huge concern for women in many parts of India, particularly in Delhi where the memory of a horrifying 2012 rape on a bus still lingers.

“Quality mobility is absolutely critical to for women’s financial independence,” said Elsa D’Silva, founder of Safecity.in, a crowd mapping platform for tracking reports of sexual abuse and harassment. “If they don’t have access to this, they either self censor and limit their own mobility or they are stopped under the guise of safety by their families from going too far from home.”

The Indian government has justified internet shutdowns as necessary for maintaining public safety, but it refuses to be transparent about them, preventing the collection of hard data that can showcase the impact.

Neither India’s Department of Telecommunications nor its Ministry of Home Affairs maintain a record of internet shutdowns ordered by state and local government.

In a submission to the Rajya Sabha by G. Kishan Reddy, minister of state in March 2021, justifying shutdowns, he noted “Centralized data of internet shutdown is not maintained by the Ministry of Home Affairs.”

This has baffled the country’s own Parliamentary Standing Committee on Communication and Information Technology.

In a February report, the Parliamentary Committee said that it was “not satisfied” with the rationale offered by both the Department of Telecommunications and Ministry of Home Affairs.

“They have made the plea that police and public order are essentially State subjects and suspension of Internet does not actually come under the ambit of crimes. This has resulted in the absence of any appropriate mechanism to verify the number of internet shutdowns in the country and the reasons for imposing such shutdowns,” said the committee, further observing that “in the absence of such a verifiable mechanism, the Department/MHA do not have any means to ascertain whether internet shutdowns have been clamped strictly as per the Suspension Rules or the order given by the Supreme Court.”

This is significant because without records, people cannot be held accountable. Without documentary evidence, citizens can’t file complaints.

And without reporting on the shutdowns, there is no proof they are effective at all.

“Rumors don’t stop just because the internet is shut down,” Bajoria said. “Instead, they prevent people from being able to verify facts and even hinder the government from using it as a medium to put out accurate information or counter misinformation in an effective manner.”

The United Nations has long batted for access to the internet to be declared a Human Right.

In India, these shutdowns and their widespread impacts are proving just how critical it is to everyone’s livelihood—and just how cruel these wanton acts can be, a burgeoning authoritarian regime flicking a switch on a whim and bringing society to a grinding halt.

Modi ran on the promise of Digital India and “Achchhe Din” (good days). As his re-election approaches in 2024, India’s rampant use of internet shutdowns makes his initiatives look less like the connected cities of the future and more like isolated digital prisons.