In the early hours of Jan. 29, a police team dressed in plainclothes landed in Hyderabad to pick up Mohammed Khadeer Khan, a daily wage laborer, from his sister’s house, on suspicion of jewelry theft in his hometown of Medak 120 kilometers away. Two days earlier, a young woman filed a police report claiming a thief threw chili powder into her eyes and ran away with her gold chain on a dimly lit street in the evening.

Khadeer’s thin wiry frame and grown-out hair vaguely resembled the culprit who was captured, passing along the route of the incident, by two closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras.

The cameras are part of a vast surveillance web established in the southern state of Telangana that boasts over 1 million CCTV in public spaces. The cameras, many of which are hooked up directly to facial recognition technology, can capture low-resolution images and identify individuals even when wearing masks and disguises, providing police with leads to trace suspects in crimes.

Images captured in the CCTV feed are processed through an internal database named TSCOP, containing fingerprints, photographs, case details, and the location of over 160,000 repeat offenders and ex-convicts.

A facial recognition app helps police compare and match the images based on similarities with the existing records.

Information from one CCTV camera equals the work of 100 policemen, former director general of Telangana Police Mahendar Reddy proclaimed.

However, activists and digital rights organizations, including global non-profit Amnesty International, have singled out Telangana’s vast network of surveillance for “putting human rights at risk.”

The culprit’s face in the CCTV recordings of the chain-snatching incident was hidden with a handkerchief and not clearly visible. Yet, the police strongly suspected him to be Khadeer, believing there was a resemblance of physical attributes and because he was previously booked for selling stolen jewelry.

“For five days the police beat him mercilessly. Every part of his body turned black and blue, he couldn’t even walk straight out of the police station or pass urine,” Siddeshwari, Khadeer’s wife told Daily Dot. “He could never harm anyone, not even a stray dog, so the act of stealing and throwing chili powder into the eyes of a woman is unthinkable,” she said.

Khadeer was released after the police investigation determined from his call records and location data that he was in Hyderabad at the time of the robbery and verified that the man in the video was not him.

A video of his testimony shivering on a hospital bed, narrating the torture in graphic details went viral on X.

On Feb. 16, he died in a government hospital while undergoing treatment for multiple fractures, dislocation of his spine, and renal failure.

A fact-finding team of social activists surmised that Khadeer was arrested illegally without any warrants and tortured by the police merely based on “mistaken identification” from the CCTV footage.

As India’s digital infrastructure rapidly expands across public and private spaces, the adoption of technologies such as artificial intelligence, smart learning, algorithmic systems, and facial recognition by government entities in the areas of governance, health, services and utilities, and law and order has raised concerns about public liberty and welfare.

Privacy experts fear the collection of personal sensitive data, facial analytics, and biometric information on such a large scale with no national guidelines, could be used to further entrench discriminatory practices against millions of marginalized communities and minorities, who are already victims of persecution in an unequal society.

Khadeer’s death encapsulates the dangers of mass surveillance and threats to right to privacy of the most vulnerable.

“Khadeer is a fall out of a systematic oppression that has been built in Telangana over the years with no legal safeguards or protections for people,” said Srinivas Kodali, an independent researcher tracking digital infrastructures, surveillance, and privacy.

Telangana’s ruling party Bharath Rashtra Samithi (BRS), credits the tech-savvy policing for fostering a peaceful atmosphere, pivotal to the development of the state. The state has won several awards from the tech industry for its outstanding implementation of digital initiatives including the electronic surveillance system.

Kodali underscores its importance as a critical tool for the authorities to manage unruly crowds, and curb internal disruptions and protests. But the encroachment of mass surveillance, he says is “social, political and economic” in nature and an effect of private IT companies colluding with the government to sell their advanced technologies and software for monitoring of civilians.

Telangana, however, isn’t an outlier in the realm of electronic surveillance. The wide deployment of CCTV cameras has become an inescapable part of life in India.

Even though Telangana is a non-Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) state, its tech surveillance set-up, which allows police to draw up a 360-degree digital profile of any resident simply on their phone number or name, has become an aspirational template for Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government to build its own national database to track every citizen.

Documents show Telangana has offered the Union government the opportunity to replicate its system, to profile and track each of India’s over 1.2 billion citizens.

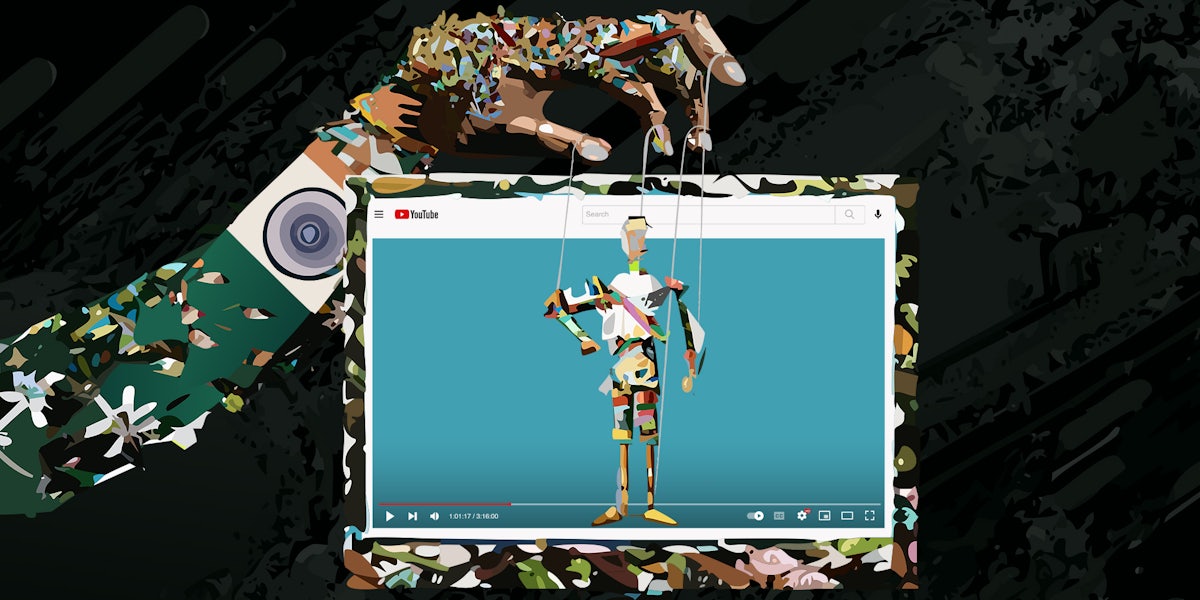

The prospect of an integrated surveillance system spanning the entire length and breadth of India seems alarming given the right-wing government’s multifaceted digital campaign to push its Hindu nationalist agenda. The BJP has used every mechanism at its disposal, from hijacking social media platforms and WhatsApp to spread divisive and hateful propaganda, imposing arbitrary internet shutdowns, deploying hacking, and attacking free speech to stifle independent news media.

Telangana’s rise as a surveillance state can be traced back to 2013 while it was still part of Andhra Pradesh state. In the aftermath of Islamist terror attacks, the AP government amended the Public Safety Act and made the installation of CCTV mandatory in popular public spots to detect security threats. Over the last decade, Telangana has added more than a million CCTV cameras, making Telangana the state with the highest number of CCTVs in the nation.

After it became a separate state in 2014, Telangana police shed its colonial functioning style in favor of modern tech-savvy policing for efficient crime prevention and detection.

The state provided over 6,000 hand-held tablets with a range of customized apps containing facial recognition technology, digital crime mapping, geotags of landmark and sensitive locations, and patrol vehicle tracking systems to all police officials.

Last August, the state police opened the doors to a first-of-its-kind Integrated Command & Control Centre in Hyderabad, with a state-of-the-art Technology Fusion Center, which gives police officials access to all its tech-based applications and integrates live feeds from the million CCTV cameras installed all over the state.

“The tech evidence has enormously improved policing and increased the conviction rate,” said joint commissioner of Hyderabad police, V. Satyanarayana.

A decade ago, police faced typical hurdles in conducting investigations: collecting evidence, gathering eyewitnesses, and ensuring they don’t turn hostile in the court.

“Even then the courts would give the benefit of doubt to the accused,” Satyanarayana added. Now, he said, “Technology cannot lie. Hyderabad is flooded with CCTV cameras; No one can escape after committing crime. No important cases or heinous crimes have been undetected. No innocent has been implicated.”

As part of digitization initiatives, the state police launched mobile phone-based apps that encourage common people to become citizen police and report suspicious activities or persons. The Hawkeye app, for instance, has over 3 million downloads and is popular among the middle class to verify their domestic help and tenants, report crimes, and seek instance assistance from the police.

The problem with this kind of surveillance set-up, which has mass acceptability, Kodali pointed out, is that its ill effects are almost always felt by the marginalized.

“Policing and surveillance is always performed on the ‘others’,” he said.

In the post 9/11 U.S., the chilling effects of surveillance were mostly felt by Muslims, Sikhs, and ethnic minorities.

In India, too it is Muslims, dalits, adivasis, tribals, and immigrants, those perceived as ‘outsiders’, whose rights are frequently trampled due to a systemic communal and caste bias.

Telangana’s capital city Hyderabad, known as India’s HITEC city, is infested with electronic surveillance and police there have used it to profile and harass its ethnic minorities.

Once you spot it, you can you see it everywhere. From the FRT-enabled Digi Yatra at the airport, to high-end surveillance at the railway stations and automatic number-plate recognition at traffic signals, the city’s 494,000 CCTVs are an ominous part of the public facilities.

The majority of the people don’t question this system, as they don’t understand its concerns, lawyer Abdul Raheem said. “They don’t mind it because they are told it is for their good and to keep them safe.”

That is until the system perceived to be harmless turns authoritarian, harassing common people and placing them in an endless surveillance cycle.

In February, just before the COVID-19 lockdown, Dawood Khan, 30, a management professional with Amazon, was casually smoking a cigarette outside a hair salon in Shantinagar neighborhood, when a cop on a bike stopped by and took his photograph.

“It was so random because I was not doing anything illegal,” he said. Although he was smoking within the saloon’s premises, the cop noted down his personal details, took his fingerprint scan, confiscated his Aadhar card, and issued a challan (bill) of Rs 250 for public smoking.

“I was shocked and didn’t know how to react. I also needed my card back and the fine was not a big sum, so I didn’t object,” Dawood said. But his data is now entered into a system he can never remove it from.

The practice of taking photographs and fingerprints grew arbitrary and oppressive during lockdown. The photos are uploaded on TSCOP, which is connected with the national Crime and Criminal Tracking Network and Systems (CCTNS) database containing records of fugitives and “wanted” criminals from all over India.

After his photos were forcefully taken during the lockdown in May 2021 without being accused of any crime, activist SQ Masood filed a lawsuit challenging the police’s use of the FRT as illegal, biased, and an infringement of right to privacy.

In the prevalent social-political environment where religious minorities, especially Muslims, are blatantly persecuted, he fears a significant potential for misuse of photos and biometrics.

“Digitization of policing can be disastrous for the poor and the marginalized who are stereotyped by discriminatory policing. We can’t just stop the tech if the system is biased,” he said.

Police monitoring is rampant in Muslim-dominated areas and against young boys and men, who can be detained and photographed for simply being out on the streets at night.

On August 12, an early morning military-style cordon and search operation, usually conducted in militancy-inflicted Kashmir, startled the residents of Hafez Baba Nagar in Hyderabad’s old city. A team of over 100 policemen combed through the area, checking every household.

“We were scared at first but the police were nice, they said they’ve come to do general inspection and look if anyone is hiding any stolen vehicles or goods,” Shakira Begum, a resident said. “They asked our name, how many family members, employment details, mobile number, and Aadhar card information.”

Just few months ago, policemen, under the guise of a drug detection push, stopped commuters and checked their belongings, including their phones and WhatsApp messages, to see if they had used any keywords like ganja (marijuana) or charas (hash).

There is real danger of such practices being extended, used to crack down on civilians during anti-government protests and demonstrations, throttling free speech and free expression, all as Modi pushes an authoritarian regime further and further.

Collection of personal data, photographs, finger scans, and phones of people who are not convicts or suspects without due warrant by the police or any government agencies is illegal.

But that hasn’t stopped authorities in Telanga.

Researchers have noted Telangana’s data collection style closely mirrors the National Security Agency’s (NSA) “collect it all” approach to surveillance.

“The data generated is huge but there is no information in public on where the images are stored. There are no guidelines for recording or retention of CCTV feed and facial recognition scans either,” said Anushka Jain, an independent data privacy expert. “Moreover, there is absence of regulation and oversight. Even the Data Protection Act exempts government authorities collection of information for surveillance in the name of national security.”

Kumar Sambhav, journalist and researcher with the Center for Information Technology Policy (CITP) at Princeton University, said the surveillance set-up in Telangana is not an exception and state governments across India are individually building searchable databases for governance and monitoring purposes.

“The surveillance infrastructure is being built in the name of efficient delivery of welfare schemes and better governance but these same tools can be misused for unhindered surveillance,” he said.

In Telangana’s case, the set-up initially built by the police for profiling criminals and repeat offenders was scaled up into an e-governance project, he said.

A unique smart governance platform, called Samagra Vedika, links 30 different government agency databases and can build a comprehensive digital profile without the use of an Aadhar ID for each of the state’s 30 million residents.

Reports suggest that officials can draw up any individual’s digital profile with a 96% accuracy by simply feeding in a phone number, a name, or an address, without relying on any biometrics.

But this e-governance database, combined with the prevalent public video surveillance, creates a frightening environment of state-sponsored snooping.

And it will only grow in the future.

The national registry database envisaged by the BJP will automatically record and track minute demographic details of every citizen: buying a new SIM card, opening bank accounts, staying in hotels, registering for marriage, moving cities, taking up new employment, or getting admitted into college.

Separately, the Home Affairs Ministry has launched plans for a centralized Automated Facial Recognition System (AFRS) with a searchable image database to be used by all police officers.

According to the data from Project Panoptic, a tracker from Internet Freedom Foundation which has petitioned for a ban on FRT across the country, various government authorities have installed nearly 170 surveillance systems.

With Indian democracy drifting towards authoritarianism, the rapid expansion of electronic monitoring and digital tracking by the police and government agencies poses endless harms to critics and citizens like Khadeer, who have unknowingly become victims of the system.

Like Siddeshwari, Khadeer’s wife, who previously had little grasp on concepts like the right to privacy or data security, which were infringed upon in Khadeer’s case.

She is, however, determined to fight for justice for her dead husband and prove his innocence.

“His story is out in public now, so we know (about the abuse of CCTV systems). I only wish that other innocent people don’t die like him.”