In reporting a story for Nautilus on the relationship between cryptography and the human brain, Virginia Hughes encountered a researcher with an interesting idea about the future of private security: instead of memorizing simple passwords, why not store complex ones deep in our subconscious?

Working with cognitive psychologists, Hristo Bojinov, a graduate student of computer science at Stanford University, has come up with an intriguing solution to so-called “rubber hose” attacks, whereby someone compels another to reveal a code under duress. The way to protect yourself, Bojinov suggests, is a game that “allows you to learn a code not with conscious, explicit memory—which is vulnerable to outside pressures—but rather with implicit memory, which you’re not consciously aware of, and therefore, could never be compelled to divulge.” (You can give it a whirl yourself.)

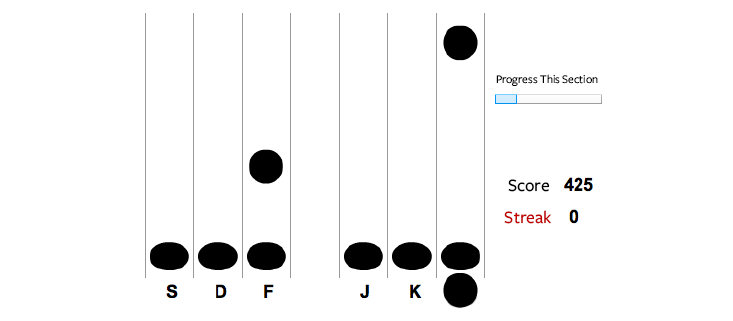

In the same way a musician’s fingers can rely on muscle memory to produce a song without the musician thinking about each individual note, one can store the pattern of a 30-character password by practicing a little coordination task. Circles track down columns, each of which corresponds to a letter. Your job is to hit the appropriate key to intercept each circle as it touches down. Play for an hour or so and the lengthy password is effectively seared on your mind, though you’d never know it.

Bojinov reasons that particular response times would provide an added layer of security. Even if an attacker knew your online banking password, for example, they’d have to key it in with something approaching your speed—i.e., much faster than the average person can generate a new, unfamiliar sequence. And a modified “rubber hose” approach, where, say, a victim is forced to enter the code at gunpoint, would also likely fail, given that stress would alter performance.

It’s a fascinating concept, to be sure, and an ingenious understanding of the brain’s architecture. Still, 30 characters is a lot. Your average Internet user would probably rather be hacked than play a modified version of Space Invaders every time they want to check their email.

H/T Nautilus / Illustration by Jason Reed