Before the justice department charged Aaron Swartz with felony hacking, the computer prodigy turned Internet rights activist had already accrued quite a file at the FBI.

Swartz committed suicide on Jan. 11, 2013, after refusing a plea that would have marked him for life as a felon. Now, the FBI has declassified its Swartz file, as it usually does after the death of a subject. So blogger DSWright filed a request for a copy.

The 21 pages of Swartz’s 23-page file, which Wright summarized in a post Monday, are bizarre, to say the least.

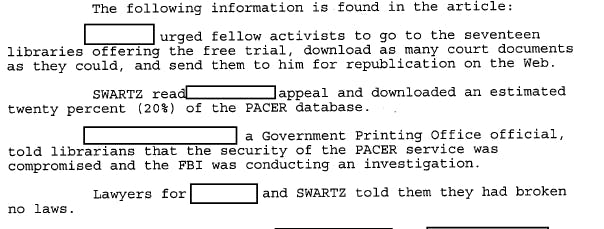

Swartz attracted the FBI’s attention for doing nothing illegal. In 2008, PACER, the federal court system’s digital archive of public court documents, opened its doors to 17 public federal depositories. The documents usually sat behind a 10-cents-per-page paywall. Swartz exploited a loophole to download 18 million pages, or 20 percent of the database. The PACER system was hit with one request every three seconds while Swartz was downloading the files.

In its file on Swartz, the FBI estimates this the “value” of the pages to be $1.5 million. The figure comes from PACER’s 8-cents-per-page fee, but in actuality all documents on PACER are in the public domain. Swartz wasn’t stealing. He had quite brilliantly exploited a loophole to download public documents.

Regardless, the FBI was not pleased. According to the files, they traced the IP address behind the downloads to Swartz and tracked him down to his Chicago area residence. Agents cased Swartz’s house, trying to see they could surveil it without detection.

They gave up. According to the document:

“House is set on a deep lot, behind other houses on Marshman Avenue. This is a heavily wooded, dead-end street, with no other cars parked on the road making continued surveillance difficult to conduct without severely increasing the risk of discovery.”

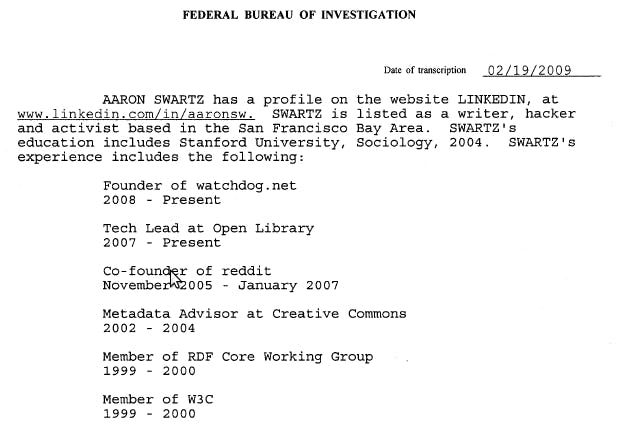

As agents were scoping out his home, others were undertaking employing dubious research methods as they tried to learn about Swartz’s background. A large section of the document is copied verbatim from Swartz’s LinkedIn profile and his Facebook page. (Tip to felons: If you want to send the FBI on a false lead, just toss some lies into your social media presence.)

Here’s the LinkedIn section:

And Facebook:

Later on, the FBI summarized a New York Times article on Swartz’s PACER feat. Strangely, in the public release of the documents, the FBI redacted many of the names and facts that remain completely uncensored in the New York Times itself.

The case appears to have fizzled out after the FBI finally decided to contact Swartz, and he in turn contacted his lawyer, who refused the interview. According to the FBI, the pretext for the interview was to learn how PACER was compromised in the first place.

The FBI closed its investigation of Swartz four days later.

It’s worth noting that Swartz requested and acquired his own copy files in 2009, and he published an abbreviated version to his blog at the time. You can view the full FBI file below.

Photo by dsearls/Flickr