Dear game developers, writers, streamers, academics, analysts, and gamers: We need to talk about sex.

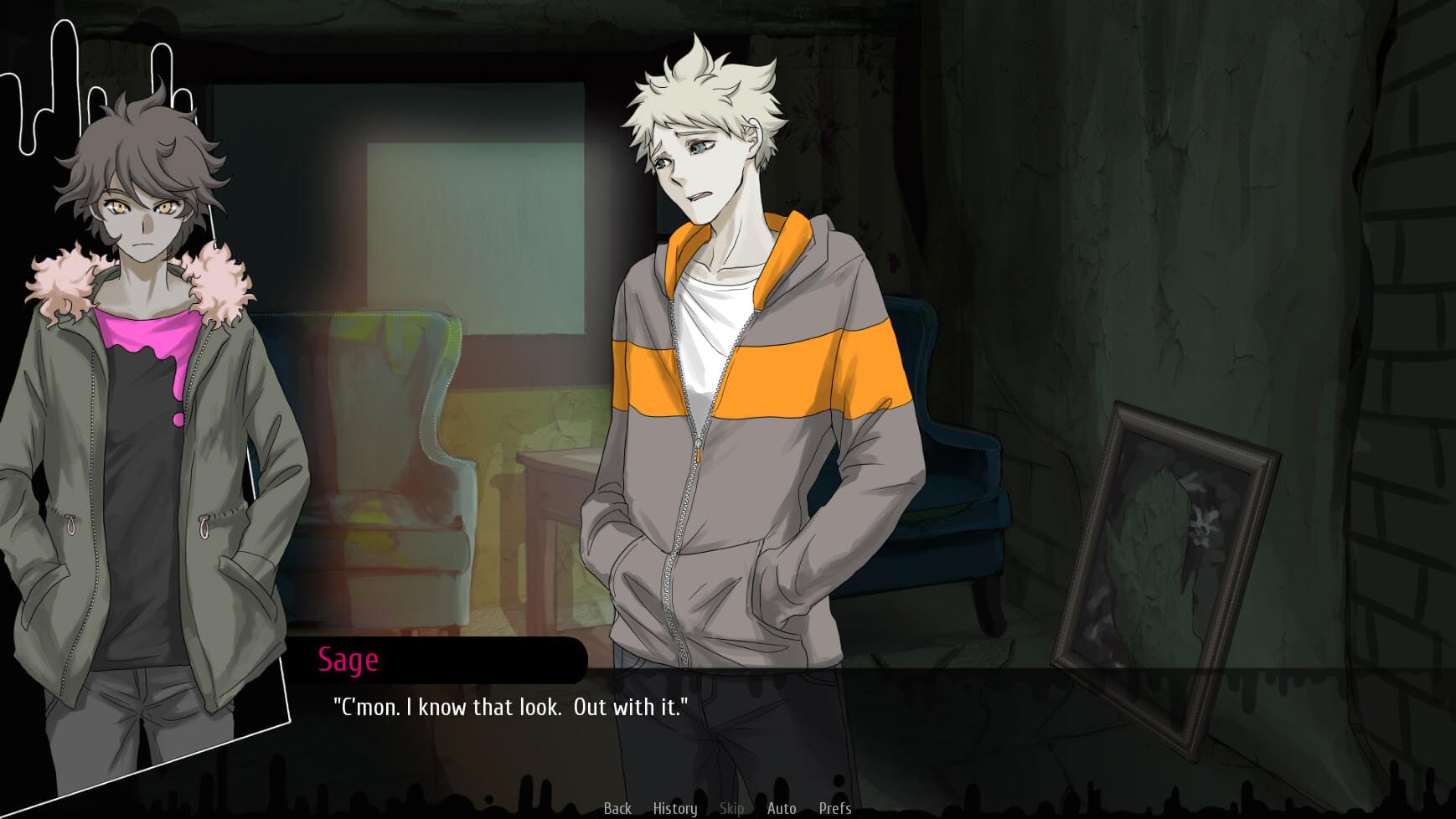

When I rode into Boston for the PAX East festival last month, sex wasn’t exactly on my mind. That changed when I passed the Indie Megabooth’s Visual Novel Reading Room and saw a queer adult game called West Falls. In my review, I called West Falls “the gay adult horror game that made a grown man run away.” It’s true: It did make a gamer run away because of its homoerotic innuendo, developer KV Hice told me.

But as of this article’s publication, no other writers at PAX covered the game or its significance as an openly queer adult title. That’s a shame because West Falls doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It’s a promising 18+ game stuck in the cogs of an industry that has much to say about graphics, framerate, and release dates—and very little to say about queer desire.

In 2015, I borrowed a book called The State of Play from my county library in New Jersey and read an essay by merritt k called “Ludus Interruptus: How Digital Games Struggle with Sexuality.” Adapted from a 2014 talk, k’s writing made me realize that you could report critically about sex in games and push for a more nuanced understanding of how game design reinforces (or challenges) heteronormativity. The piece stuck with me because it’s still relevant today. Not much has changed.

As I reported last year, games media is pulled in myriad directions that prevent it from embracing adult content. Between corporate heads that crack down on kinky writers, editors who shy away from criticism about smut, advertisers dictating content, and sexual timidness on the part of the industry’s most established writers, adult games languish in the press.

Not much has changed around discussions on queerness in games, either. Titles like Heaven Will Be Mine, LIONKILLER, Extreme Meatpunks Forever, and one night, hot springs have introduced more nuanced discussions around queer experiences in games, but these titles rarely get the same level of sustained press coverage that major, corporate publishers’ games receive. Thus, Doom Eternal gets more coverage than Dominatrix Simulator.

“Don’t you think it’s a little sad that violence goes more or less unquestioned in games until it’s consensual? Don’t you think it’s depressing that we’re overwhelmingly still more okay with violence than sex in games overall?” merritt k wrote in 2015. “I do, and I’m trying to change that.”

Games and sexuality journalist Kate Gray came into sex writing accidentally. Gray was impressed by a Dragon Age: Inquisition plot that involved a non-playable gay character who rejects the player. The idea that an NPC wasn’t “player-sexual” was new to her, so she wrote a piece for the Guardian that same year. The article went front page, and she quickly received messages all too familiar to games critics: Why does this matter? It’s just a game.

“From there I just realized how much I like writing about romance in games which obviously spiraled into just talking about sex in games,” Gray said. ” I realized with a lot of the media I consume that the sex-positive aspects […] are pushed to the side.”

Some things are shifting, for sure. Gray says the games business is having a more nuanced conversation around how sexuality interacts with identity and making room for asexual and aromantic experiences. Sexual agency in games is getting more complicated, too, as games change how non-playable characters interact with players. But these are exceptions to the rule.

“In terms of what hasn’t changed, I think sex-positivity is still on its way to become a thing,” Gray said. “I think a lot of people are still grossed out or amused by sex.”

In their book Video Games Have Always Been Queer, author Bonnie Ruberg argues that the gaming community suffers from a fear of reading “too closely” into a game. Pulling queer narratives from games that are not “supposed” to be queer is frowned upon. Of course, that’s exactly how people relate to art: by extrapolating details and relating them back to their own lives.

So what happens when queer developers create games that challenge the status quo? Well, they get used. Ruberg’s new book The Queer Games Avant Garde, out this month, features interviews with 21 queer developers creating games outside of the mainstream games industry. Ruberg’s book reveals indie creators’ labor is not just “undervalued,” but the industry’s “dominant discourse around ‘indie’ games valorizes the work of game-making only when it ‘pays off.'”

In other words, if your game isn’t a success story (or isn’t trying to be one), games journalists will ignore you. And if you somehow did turn a profit, someone outside of the queer community will find a way to take advantage of your hard work.

“For the artists interviewed here, creating indie games and the community networks that support them also requires forms of labor that are rarely compensated, are highly gendered, and remain largely invisible, such as emotional labor,” Ruberg warns. “Even as queer games inspire change in the mainstream industry, which in turn reaps financial benefits, queer indie game-making itself remains precarious.”

With limited funding and little marketing experience, how do you get the word out about your game? PAX’s Visual Novel Reading Room is one answer. The room started in 2017, and its inspiration “isn’t very glamorous to say,” co-organizer Arden Ripley told me. A couple of visual novel developers were struggling with the costs associated with a booth, so they all pitched in. Developers work with one another to organize the booth and learn how to pitch each others’ games. It’s a rare hands-on promotion opportunity for queer creators.

“A big part of it is that my first PAX was in 2013, showing off my visual novel Hate Plus, and honestly, I had a really hard time with it! I’d never seen anyone show a visual novel on the show floor before, and it showed,” fellow organizer Christine Love said. “I didn’t know how to pitch the game to people, I didn’t know how to set up a booth, and I definitely didn’t know how to make a demo that works well on the noisy show floor … I wanted to help pass on some of that knowledge to other narrative game developers, too.”

One year after I read merritt k’s piece on sexuality and games, something else changed my mind about games and sex: Love’s 2016 adult visual novel Ladykiller in a Bind. Also known as My Twin Brother Made Me Crossdress as Him and Now I Have to Deal with a Geeky Stalker and a Domme Beauty Who Want Me in a Bind!!, the game stars the player as a butch lesbian who passes as her brother and engages in a wide variety of BDSM scenes with his female classmates.

Nearly half a decade later, I wouldn’t consider Ladykiller my favorite adult game ever. But its importance cannot be overstated. It was one of the first 18+ games available on the Humble Store. Publications that rarely covered adult work let writers review it. Steam (eventually) made exceptions for its release in 2017. It was, to the best of my knowledge, the first adult game available to play at PAX East. It was a thrill to experience, like the first visit to an adult bookstore or strip club.

It’s unsurprising Ladykiller received so much press coverage. By then, Love was a recognized face in the indie game development world, and having a pre-built audience certainly helped spread word of mouth. To Love’s surprise, the game broke even in just nine months; she calls it her “biggest launch by far.” But much has been written about Ladykiller, and not much of that interest has transferred over to curiosity around sex in games.

Ladykiller became the press-approved adult game in an industry where journalists lacked the competency to discuss leathersex and BDSM. “People want to talk about it, but they don’t necessarily have the vocabulary to discuss kinky lesbian sex games,” Love said. “There are now journalists who both have that fluency [in queer porn culture], and can teach this to people who aren’t familiar but want to know more about hot lesbian sex games.”

PAX East’s 2020 Visual Novel Reading Room featured two queer adult games: West Falls and Love Shore. The latter focuses on the titular Love Shore, a cyberpunk city where a biotech corporation is creating “non-aging” humans from raw DNA. The game’s entire cast is LGBTQ with multiple love interests. West Falls throws three college friends into a paranormal horror tale steeped in the boys’ love genre.

West Falls’ PAX East demo doesn’t have any explicit sexual content, but it’s unafraid to be raunchy. The preview ends with the campus’ Officer Hawkins restraining the player character Sage from behind and asking whether he will be “a good boy and cooperate.” On the player’s choice, Sage will tease Hawkins, asking if he has a “thing” for “strapping young college guys who do whatever you say.” The game’s full version is set to be even more unapologetically kinky and embrace “messy” adult content with a “boldness,” Hice said.

“Nobody bats an eye anymore over sex scenes in 3D games like The Witcher or Bioware titles, but when you’re asking someone to sit down and read about sex, it can feel different,” Ripley explained. “It’s more intimate, which can mean it’s scarier, which is why I think people can be a little resistant to it. So I hope showing off these beautiful works can help overcome the stigma of exactly what an ‘adult visual novel’ is supposed to be, because there’s so much variety out there!”

This is certainly a fresh breath for a show like PAX. But the lack of queer sex representation is a problem that cannot be fixed with one or two booths. Queer trans adult game Hardcoded hasn’t yet tabled at a gaming convention despite flattering write-ups everywhere from Kotaku to Rock Paper Shotgun because it’s unclear if conventions like PAX are OK with 18+ material. This becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy: If no one is showing an adult game, adult game developers won’t apply to show their work.

“I’m extremely new to the idea of publicly showcasing the game, but I’m not like, embarrassed or anything. At least, not anymore,” Hardcoded developer Kenzie Stargrifter told me. “Tabling at a [convention] somewhere sounds cool as hell but I don’t know of a con that would allow Hardcoded.”

The Visual Novel Reading Room, Ladykiller in a Bind, and “Ludus Interruptus” were all introduced in the mid-2010s and are part of a much longer legacy discussing sex and games. Nina Freeman’s How Do You Do It? looks at sexual discovery from an 11-year-old’s point-of-view. Cara Ellison’s Rock Paper Shotgun column S.EXE unpacked sexuality in game design. Anita Sarkeesian’s Feminist Frequency opened a much larger discussion on the messages games have about women, sex, and toxic masculinity.

Yet, despite all of this hard work over the past decade, progress is happening at a snail’s pace. It’s not enough to simply say sex in games can be inclusive. Gaming’s relationship with sex needs to change first.

Sarkeesian’s work suggests the problem starts with how women are represented. Merritt k’s 2015 piece implies gaming design’s legacy is wrapped up in a world of violent confrontation and aggression. Exploring queer sexuality then relies on “revising our ideas about what games are and can do” so game developers can “explore intimacy, play, and human connection” in sex. Both of these things are true. But there’s a missing piece to the puzzle: sexual shame.

Dr. Alexander Kriss is a New York-based clinical psychologist. His upcoming book The Gaming Mind explores games’ legacy as one filled with deep-seated intimacy and shame. On the one hand, games are an outlet for feelings that are difficult to process: When we cannot find privacy or empathy in the real world, Kriss argues, games becomes a conduit. But it’s not merely enough to find catharsis through play. If we want a healthy relationship with games, we have to understand why we play the way we do and how we think about games as a medium.

“The burdens of history that must be sloughed off are the long-standing incuriosity around why we play games and, above all, the shame associated with doing so,” Kriss writes. “Shadows, once brought into the light, have the power to redirect energy away from self-loathing and judgment and toward a truer appreciation of gaming’s potential.”

Sexual liberation is an active process and a deeply introspective one. A field that cannot talk about the sociocultural values in its own artwork cannot be expected to have open, honest, and shame-free discussions about sex. Certainly, finding sexual liberation is easier said than done. But for a medium struggling with sexual maturity, honesty is the first step to adulthood.

READ MORE: