Ever since the COVID-19 pandemic forced us into lockdown back in March, we’ve intentionally (and often unintentionally) looked toward our entertainment to try and make sense of it all.

We’ve leaned on escapist fantasies and comfort nostalgia, stories that took place in a time where the current pandemic never existed. We’ve tried to make ourselves feel better by watching and reading more dystopian stories because, well, at least we know some of those characters eventually make it out of their fueled nightmare. We’ve already seen several COVID documentaries, shows about COVID quarantine, and broadcast networks trying to incorporate COVID storylines into their shows with mixed results. Many 2020 releases like Palm Springs and timeless classics like Jaws became unintentional metaphors for our reality, and the logic of reopening Isla Nublar after the events of Jurassic Park made so much more sense. Clever horror movies and exploitive thrillers have already made their way into our homes as we’re still living it.

I often leaned on that comfort fodder this year. But nothing seemed to embody the essence of the inexplicable reality that was 2020 more often to me than Damon Lindelof’s television universe.

That’s not to say that Lindelof “predicted” 2020, that’s far from it; it’s not a completely perfect analog, not to mention that in many ways, they couldn’t be more different than our reality. For much of its first season, Lost (2004-2010), which he co-created with J.J. Abrams and helmed with Carlton Cuse, came on the coattails of Survivor, and initially, there were only hints of the sci-fi roots it would eventually embrace. The Leftovers (2014-2017) was an adaptation of Tom Perrotta’s 2011 novel that partially served as a metaphor for a post-9/11 America; Perrotta joined as co-creator. Watchmen was a continuation of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ iconic comic that explicitly drew connections between white supremacy and policing (connections that countless activists, scholars, and filmmakers have made for decades, if not centuries, before Watchmen ever did).

And it wasn’t just Lindelof’s visions; every one of those shows was shaped with the help of its writers, directors, and actors, which Lindelof has made a point of highlighting even as his shows garnered him critical acclaim and accolades. They’ve been great meme fodder like so much of our entertainment, but each of them, in their way, also offered something of a reflection of ourselves.

‘Live together, die alone‘

Lost is a solid quarantine binge. It’s the kind of series, at 121 episodes over six seasons, that isn’t that intimidating to start in lockdown. And while Lost is, for better and for worse, often remembered for its divisive ending, it’s had something of a resurgence in the past couple of years between Game of Thrones’ even more polarizing final season leading some fans to reevaluate Lost’s ending and the 10th anniversary of the series finale earlier this year.

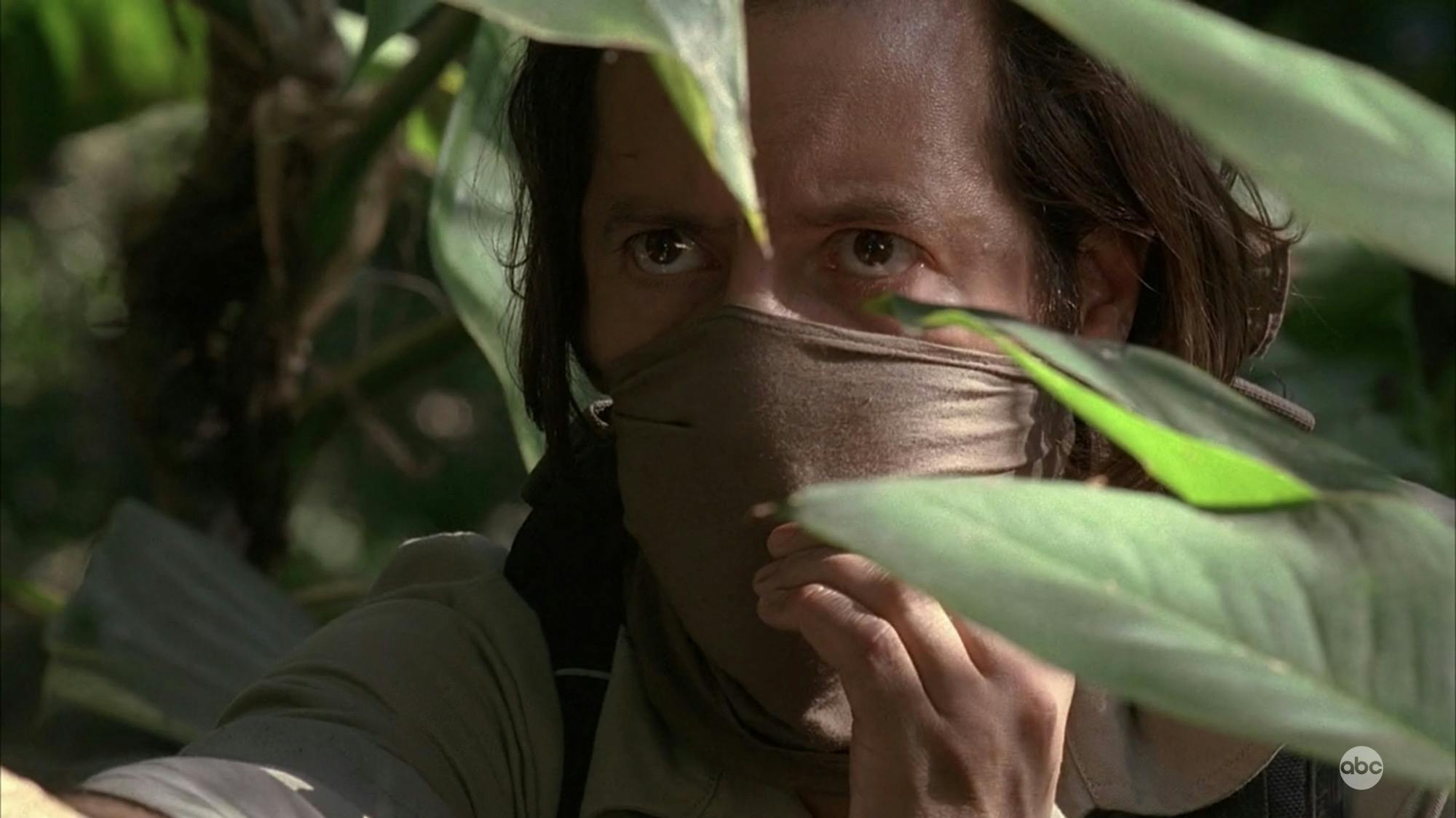

By the time COVID-19 sent us into lockdown, I’d been slowly rewatching Lost for months, the first time I’ve revisited the series since it first aired. But the idea of quarantine was written all over the show, whether it was a wayward haircut or the state of Jack Shephard’s (Matthew Fox) beard becoming a metaphor for quarantine. It was particularly prevalent in season 2 with Desmond Hume (Henry Ian Cusack), who spent three years in almost pure isolation in an underground hatch because he’d been told that there was a pathogen outside that could kill him.

When we first met Desmond in the season 2 premiere, he already settled into a solid routine you could tell he followed daily for months at a time before he eventually left the sanctuary of the Hatch. Later, in season 4’s “The Constant,” Desmond scheduled a Christmas Eve phone call with his ex-girlfriend Penny (Sonya Walger) for eight years in the future to prevent him from becoming irreversibly unstuck in time; when they finally do get on the phone in one of Lost’s most emotionally resonant scenes, Desmond and Penny are plagued with connection issues.

No matter how much Lost leaned into its sci-fi roots, we were always reminded of the emotional toll that the separation carried. Scenes like that Christmas Eve phone call or seeing Juliet Burke (Elizabeth Mitchell) sobbing in a season 3 flashback episode after she was shown footage of her sister Rachel, who Juliet hadn’t seen in three years, with the son Juliet helped her conceive, hit much harder. (Even more so when you know how Juliet’s story ends.)

But a bigger overarching theme that carried Lost throughout its run? The idea that working as a cohesive unit will go a long way to save everyone’s lives versus a more selfish and individualistic path. As much as we might’ve mocked Jack’s famous “live together, die alone” speech in season 1, he’s got a point. The survivors of Oceanic flight 815 (and the allies they gain along the way) are all stronger together than they are as individuals. “We think it’s one of the unifying themes of the show: this idea that they need each other in order to survive on the Island,” Lindelof said on the May 2006 episode of the official Lost podcast.

It’s why Sawyer usually fends better when he lets others help him (and he helps them) versus stubbornly insisting he can do it all himself, but you also have someone like Desmond, who starts to flourish once he lets others in. It also often means the difference between life and death for many of its characters. In our lives, it’s amplified; we witness it every day as the number of COVID cases and deaths continue to rise.

An endless cycle of grief

When I started watching The Leftovers earlier this year, I was warned by a couple of friends who’d already sung its praise for years that while it was a little pandemic-y upfront, it wasn’t three seasons of misery porn. So while I knew what I was more or less getting into, I wasn’t expecting The Leftovers to be the best analog for the insurmountable grief that we’ve found ourselves in during the pandemic (as well as the grief we’re already shouldering), nor for a gut punch to render me speechless within the first five minutes of watching.

The show’s cold open transports us to a laundromat in Mapleton, New York on what seems like an ordinary day. One minute, a mother hears her son crying in his seat while she’s on the phone with someone, the next, the crying is gone, but so is her son. The 9-1-1 calls build up as more and more people try to explain what happened. And then, in a scene that takes place three years later, a man calmly compares the losses from the Sudden Departure to how, in centuries past, mass pandemics such as smallpox once decimated 95% of the native population. Two percent isn’t that big of a number in retrospect, he explains. It’s just one in every 50 people and that all of the players on a soccer pitch would still be here. He assures viewers that “The odds of losing someone in your immediate family are slim at best.”

In The Leftovers, the numbers barely scratch the surface. It’s impossible to begin to convey the emotional toll of what an event like the Sudden Departure, in which 140 million people vanished in an instant, could do to a family or a community, no matter how many people in your immediate family departed. Scientists, religious figures, and the government fruitlessly tried to make sense of it all; the official consensus was “I don’t know.”

The Guilty Remnant took a nihilistic approach to make sure that nobody tries to move on from the Sudden Departure and went to extreme measures to make sure people didn’t forget. In season 2, Jarden, Texas—a town that had no departures—existed in a bubble where you could pretend that the Sudden Departure didn’t happen (even though Jarden became an epicenter for Sudden Departure-related pilgrimages) until it was forced to face reality. To get some kind of closure, people could spend $40,000 on bereavement figures that look like their departed loved ones, but it was also seen by many as a large waste of money.

An episode early in The Leftovers’ final season really got to the heart of the matter as Nora Durst (Carrie Coon), who spent much of the series attempting to gain control over her life, was told that there might be a way to see her departed children again. The pain she tried to push away and hide for so long returned, and she questioned Erika (Regina King) how she didn’t go mad after Erika’s daughter Evie died three years earlier. “Evie died, and I got to bury her,” Erika replied.

The exploration of grief and how those spared or left behind by the Sudden Departure cope with that inescapable loss was one that many of us could relate to on a variety of levels, but then COVID made it all too real. It was hard enough losing loved ones as it was, but now, the rituals we usually leaned on to grieve—whether they were religious, spiritual, communal, or everything in-between—are still unsafe to perform.

So now we go through the motions, or we mourn virtually because we can’t say goodbye in-person; we mourn for the year we lost; we mourn for the life experiences we’re missing out on, the weddings and births we cannot witness; we mourn for the loved ones we only got to see through a screen. We still haven’t acknowledged the tangible loss in ways that allow for us to grieve, a loss that grows exponentially every day now that the number of daily COVID deaths is about equal to the number of people who died on 9/11, and chances are we might never truly acknowledge it; we’ve largely become numb to it long ago. And when we reach the other side, we’re still left with millions of people whose lives are irrevocably changed because of it. Will we acknowledge it then? But for now, we attempt to make sense of it all, because that’s all we can do right now.

The power of masks

Watchmen existed in an alternate future sparked by the original comics that featured Robert Redford as president, gun restrictions where you had to get permission before you could unlock your gun to fire it, and reparations for the descendants of the victims of racial injustice. And while Watchmen was a hit when it aired last year, the show gained newfound relevance just six months after the finale aired as peaceful protests across the U.S. and all over the world demanded an end to police brutality and racial injustice. Those actions led to a larger reckoning with systemic racism.

You don’t have to go far to find the many articles and essays that argue that point or interviews with the cast and crew that discussed it. The series’ best episode, “This Extraordinary Being,” told a gripping story about multi-generational trauma and revealed just how deeply embedded white supremacy and racist ideology was in the foundation of America (that episode won Lindelof and co-writer Cord Jefferson a writing Emmy).

Lindelof drew his inspiration for Watchmen from a few places, including the Ta-Nahisi Coates essay “The Case for Reparations”. He also explored the idea that white supremacy is the 2019 equivalent of the nuclear war threat that hovered over the original Watchmen. You need only watch the show to recognize our current world within Watchmen’s. Just look no further than the mask.

In the Watchmen comic, the politicization of masks is embedded within the fabric of the Watchmen comic through the examination of how the people who wear them wield power. In the show, Lindelof and his writers crafted a future in which police officers can now wear masks to mask their identities, as does the Seventh Kalvary, who are driven by a misconstrued interpretation of Rorschach’s journals. It’s established early on in Watchmen that the masked police abuse their power by terrorizing citizens in a manhunt, withholding evidence, and discarding Constitutional protections to torture suspects under question. By the end of the series, Watchmen argued that there’s more than just a suggestive connection between the Seventh Kalvary and police institutions.

For us, masks have been about protection from COVID versus the kind protection Watchmen‘s characters use them for, although much of the politicization comes from people who don’t want to wear masks because they see mask mandates as an infringement on their freedom. (And in some cities like New York, it took fine threats to get many police officers to finally comply with mask mandates.) But the police have still masked their identities in other ways: Over the summer, several viral videos featured police officers who covered up their name and badge numbers before they inflicted violence on protesters.

Through the looking-glass

As they aired, Lost, The Leftovers, and Watchmen all tackled out-of-this-world premises and how they toyed with science fiction or the divine, each of them ripe with mysteries if viewers chose to follow them. Lost took place on an island that could be moved around and jump through time, was home to a smoke monster who could take the form of the dead, and included immortal men as residents. On The Leftovers, a man named Kevin Garvey (Justin Theroux) could seemingly die numerous times and take a trip to what might’ve been purgatory before coming back to life. Watchmen had the larger-than-life Dr. Manhattan (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), whose mind experienced his past, present, and future simultaneously and could tell you how your relationship with him ended before it began, and an older Adrian Veidt who created his own utopia on Mars.

But, like so many of the shows, both old and new, that got us through the utterly unique hell that was 2020, Lindelof’s TV universe always had a mirror quality to it. You didn’t have to spend months or years in isolation with life-or-death stakes; or potentially lose your loved ones in an inexplicable event; or live in a world full of superheroes and villains alike who both wear masks. You could relate to the people who inhabited the shows because they were messy and human. Now, as we’ve sat at home grappling with the pandemic, it’s the stories themselves that have become relatable.