This post includes spoilers for Watchmen episode 6. Click here for last week’s recap.

Flashing back to Will Reeves’ time as an NYPD cop in the 1940s, “This Extraordinary Being” is one of the best TV episodes of 2019. Bridging the gap between the Tulsa Massacre sequence and the show’s contemporary storyline, it acts both as a standalone drama about institutional racism and a reworking of an old Watchmen character that turns the comic’s backstory on its head.

After swallowing a bottle full of pills containing her grandfather’s memories, Angela Abar falls into a series of black-and-white flashbacks, beginning with a young Will Reeves (Jovan Adepo) joining the NYPD. In some ways, his journey mirrors Angela’s own experiences. “What do I have to be angry about?” he asks his girlfriend (Danielle Deadwyler), who can’t understand his optimistic attitude. Denial permits him to live a more contented life, but that denial dries up as he uncovers the toxic racism at the heart of the NYPD. “Beware the Cyclops,” says another Black officer when Reeves first joins the force. It’s exactly the kind of enigmatic pronouncement you expect to hear in Watchmen, and we soon learn that the Cyclops is a Klan symbol. When Reeves arrests a white man for torching a Jewish deli, a group of superficially friendly white cops let the arsonist go free, exchanging a salute resembling a cyclops’ eye. They’re part of a “vast and insidious conspiracy” (that phrase again!) of white supremacists, with law enforcement and media propaganda working hand-in-hand.

It’s tempting to boil this episode down to its big revelation about Reeves’ secret identity, but it’s really so much more than that. Reeves’ memories draw together the show’s central themes of generational trauma and hidden history, offering a politically vibrant origin story for the masked vigilante trend. If Hooded Justice was a Black man—a queer Black man with this specific, tragic backstory—then we can reevaluate the comic in a very different light. The corny Golden Age imagery of the 1940s Minutemen team is suddenly imbued with a new emotional weight, offset by the violent schlock of American Hero Story: Minutemen, which retells their adventures for a bloodthirsty modern audience.

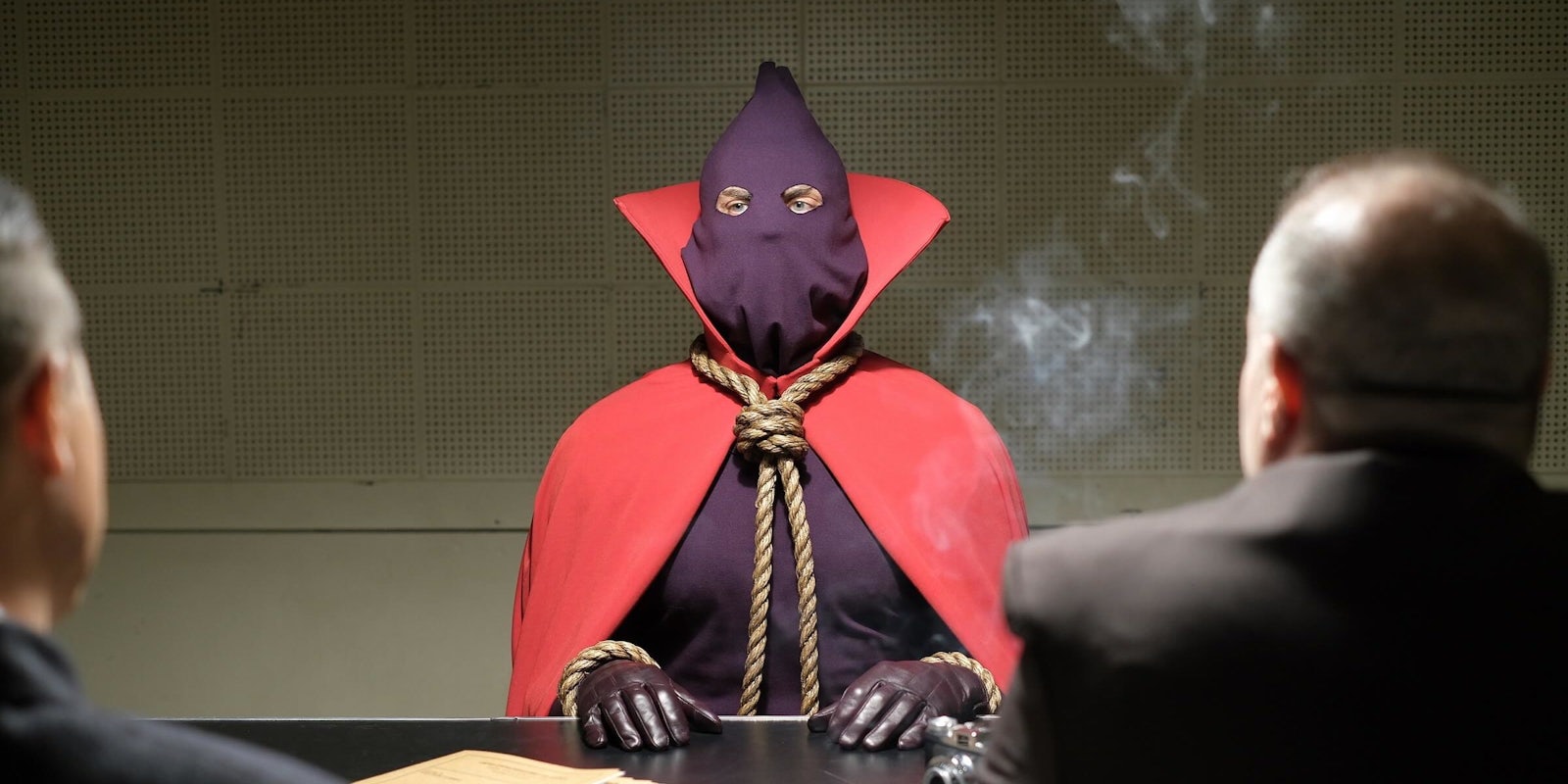

In the comic, Hooded Justice was the first masked hero. He wore a simple hood, a noose, and a high-collared cape. We know his career began when he prevented an assault in 1938, and that he kickstarted the craze for costumed crime-fighting. He was soon recruited to New York’s first superhero team, the Minutemen, led by the media-savvy Captain Metropolis, who was also his lover. And in the comic, Hooded Justice’s true identity was never revealed. The melodramatic Minutemen show portrays him as a caucasian hunk played by Cheyenne Jackson, with a detective smirkingly suggesting that the noose and hood have something to do with “sex stuff.” Will Reeves’ flashbacks tell a different story, revealing that the costume is actually the remains of an attempted lynching. After kidnapping and beating him in the street, a group of NYPD cops hang Reeves from a tree with a hood over his head. They let him go with a warning, and as he stumbles through the streets of New York, he comes across a crime in progress. Pulling the hood over his head, he lets his rage out on the criminals. And so Hooded Justice is born.

Hooded Justice was originally a callback to the simplicity of early, long-forgotten superhero comics in the 1930s and ’40s. But with Will Reeves under the hood, it feels less like a grown man playing dress-up, and more like a painful matter of necessity. As he dons the costume for the first time, his girlfriend asks him to describe the Bass Reeves movie he watched over and over as a child. Titled “Trust in the Law,” it sees Bass Reeves bring a crooked sheriff to justice, cheered on by the local (white) townspeople. That movie had a huge impact on young Will, likely inspiring him to become a cop. But as his girlfriend points out, people like Bass Reeves, and Will, are rarely greeted with applause in real life. If he wants to fight injustice, he’ll have to do it in a mask. He’ll even have to pretend there’s a white guy under there, so he paints a white domino mask under the hood. Unlike the more theatrical costumes of his contemporaries, Will’s mask has a deeply painful subtext.

When Nelson Gardner (aka Captain Metropolis) shows up, Will’s dual identity takes on another layer of meaning. Played by Jake McDorman, Gardner is a smarmy, ambitious, Aryan blond. Speaking in the crisp accent of a 1940s newsreader, he tracks Will down and asks him (as Hooded Justice) to join the Minutemen. “Why fight alone when you can have true companionship?” he asks, and Will is easily seduced. Will’s mask becomes a symbol of his double life in the closet, as well as a metaphor for how Black heroes are erased from history.

Nelson Gardner is an asshole of a very specific type. Charismatic and confident, he’s a privileged white gay man who seems cheerfully comfortable in the closet. There’s no question of Gardner acting as a real ally to Will, actively encouraging him to hide his true identity. In fact, when Will suggests that they look into the Cyclops gang, Gardner scoffs and changes the subject to the Minutemen’s advertising endorsements. Later, when Will discovers that the Cyclops caused a massacre at a Black movie theater, Gardner refuses to help: “You of all people should know that the residents of Harlem cause riots all on their own.”

Like the Seventh Kavalry, the Cyclops gang is initially depicted as a group of racist thugs, but later they are revealed to have a more elaborate endgame. The movie theater massacre was a test for cinema projectors that hypnotize viewers into a murderous frenzy, convincing Black people to hate themselves and each other. It’s an in-your-face version of the more subtle media propaganda we see throughout decades of Hollywood history. Working alone, Will storms the Cyclops factory, shooting everyone and burning it to the ground. He won this battle, but we know he has a long road ahead of him. Either because of his vigilantism or because she found out about his affair, his wife leaves him and takes their son to Tulsa. Which brings us back to his granddaughter Angela Abar. In the final scenes of the episode, we learn that old Will (Louis Gosset Jr.) was telling the truth when he said he killed Chief Crawford. Using the Cyclops’ own mesmeric techniques, he forced Crawford to hang himself. “I’m trying to help you people,” Crawford protests. “You don’t know what’s really happening here.” However, you get the distinct impression that of everyone in the show, Will Reeves is the one with the deepest understanding of how the world works.

Watchmen canon is relatively light on fantasy elements. With the exception of Dr. Manhattan, no one has superpowers. The weirdest sci-fi/fantasy aspect of the comic was the squidpocalypse in the final chapter, engineered by Adrian Veidt. He recruited a team of artists and scientists to design a fake Lovecraftian monster, powered by a cloned brain from a dead psychic. It amplified a terrifying psychic shock that killed 3 million people and traumatized an entire generation, an idea the show reverse-engineered for the Cyclops gang. While Veidt didn’t share the Klan’s ideology, he clearly emerged from an existing lineage of people experimenting with mind-control to change society.

Directed by Stephen Williams and co-written by Damon Lindelof and Cord Jefferson, this episode is so absurdly good that it’s hard to imagine Watchman outdoing itself after this. Hooded Justice’s new origin story is a brilliant conceit, packed with political meaning. Along with the new significance of the Hooded Justice costume, Will Reeves’ legacy illustrates a recurring theme in American history: the fact that Black (and often LGBTQ) people will invent something that causes a monumental cultural shift, only to be erased from the historical narrative. Reeves wore a mask to protect himself from racist and homophobic reprisals, seeking his own justice because the system failed him. He was the first masked hero, but copycats like Captain Metropolis got all the glory. Decades later, he’s a historical footnote, and everyone assumes he was white.

The black-and-white color scheme and jazz soundtrack could easily have felt gimmicky, but it really worked for me here. Viewed through Angela’s eyes (including a handful of scenes where Regina King plays her own grandfather), it’s more dreamlike than a traditional flashback sequence. Memories overlap and slide into each other. From Will to Angela to Looking Glass last week, Watchmen is full of characters who can only function by repressing the trauma of their past—which is exactly how American society works on a wider scale, refusing to confront its own painful history. Will Reeves tries to brush aside his memories of the Tulsa Massacre, but you can’t just move on from something like that—especially when the rest of the world left that wound to fester. The flashbacks become more and more insistent until we reach one of the most memorable images of the episode: a police car full of white cops, dragging a pair of ghostly corpses behind it, borrowed from Will’s memories of Tulsa. Instead of the usual idea of ghosts being washed-out and invisible, those bodies are a vivid splash of color in a monochrome landscape, forcing us—and Will—to pay attention.