The past two weeks have seen a wave of new allegations about sexual abuse and harassment in the comics industry, revealing a toxic pattern of powerful men preying on younger women, often excluding them from professional opportunities in the process. Writer Warren Ellis is the most high-profile example to date, accused of serially coercive and predatory behavior. The first allegations went public early last week, expanding to a group of more than 60 people who say Ellis used his position of power to act as a mentor while coercing them into sexual or emotionally abusive relationships.

Ellis acknowledged the accusations with a public apology last Friday, writing, “I have never considered myself famous or powerful […] It had never really occurred to me that other people didn’t see it the same way.” He apologized for the harm he caused but denies “consciously” manipulating or abusing anyone. Ellis has always had a self-deprecating attitude to his own success, but this statement goes beyond imposter syndrome into willful ignorance. He’s one of the most recognizable names in English-language comics, a writer whose career spans numerous well-known titles at Marvel and DC, beloved original works like Transmetropolitan, blockbuster movies (Red), and a position as showrunner of Netflix’s Castlevania.

It’s also clear from the recent revelations that Ellis’s behavior was known to others in the industry, but they didn’t feel able to speak up until now. Ms. Marvel writer G. Willow Wilson described the situation in a series of tweets:

“I don’t know how anybody who hung around any of the late 90’s-mid 00s Ellis forums can profess to be surprised. It wasn’t even a secret. (No idea what went on after that era because I left.) I don’t just believe these women; I saw with my own eyes the culture they were in. A lot of ppl seem to be asking ‘How is any of this wrong though?’ Here’s the thing: at that time–and still today, to a certain extent!–there was a core group of men who were *the only* way into the comics industry. There was no submission process; no applications. If you had any professional aspirations, you had to convince one of them to open their rolodex. And it was very clear there were 2 separate tracks: if you were a guy, all you had to do was be moderately talented and kiss the right ass. If you were a woman, it was different. There was a casting couch atmosphere.”

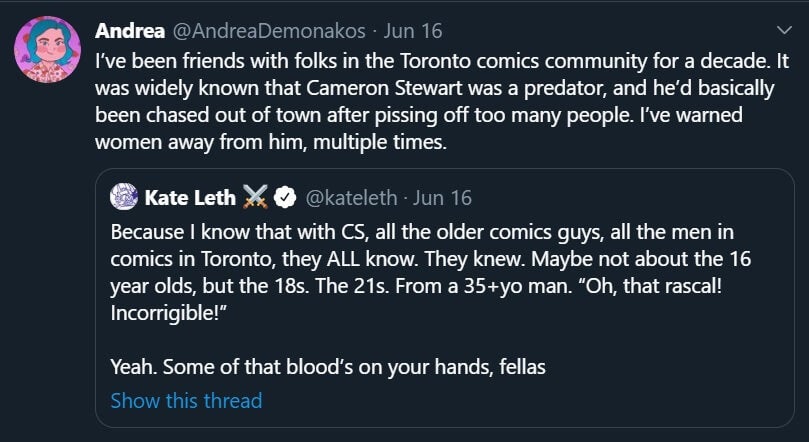

Wilson’s comments about “casting couch” gatekeepers explain why the comics community is currently in a state of meltdown. Ellis isn’t the first powerful man to be outed in this manner, and he definitely wasn’t the last. In fact, the reason why the Ellis allegations came to light was because another creator was just accused of similar behavior: writer and artist Cameron Stewart (Catwoman, Batgirl). Artist Aviva Mai posted a Twitter thread accusing Stewart of “grooming” her when she was 16 and he was in his 30s, inspiring others to come forward with tales of Stewart engaging in predatory behavior. All were in their teens or early twenties at the time, and were involved in the comics community either as fans or as up-and-coming creators, with Stewart using his position for social and/or professional leverage.

Back in 2017 and 2018, when various industries were facing their own versions of the Me Too movement, the comics community had a more muted response. Some prominent men had already been accused of sexual assault or harassment, but many continued to work in the industry. For instance, Charles Brownstein kept his job as executive director of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund following allegations of sexual assault and harassment, supported by a board of industry insiders including Neil Gaiman. (Brownstein finally resigned this week, after extensive pushback on social media.) Former Dark Horse editor-in-chief Scott Allie was demoted after biting and groping writer Joe Harris at a convention in 2015, along with multiple reports of abusive workplace behavior. He continued to work at Dark Horse in a less prominent role, editing Hellboy comics—a job that ended this week after a former coworker, Shawna Gore, published an account of sexual assault and abuse. Another Dark Horse editor, Brendan Wright (who celebrated Allie’s departure in 2017), was recently fired from several projects due to allegations of stalking and sexual harassment.

DC editor Eddie Berganza was another well-known sexual harasser who retained a position of power for years and was only fired after BuzzFeed published an extensive report on his behavior in November 2017. Over the past few years, several other comics creators were publicly accused of sexual misconduct, but it’s now obvious this was just the tip of the iceberg.

For a variety of reasons including a lack of professional support and the insular nature of the industry, many victims did not feel able to come forward. The past two weeks saw a tipping point, both in terms of the volume of survivors sharing their stories, and the way these experiences are being discussed. Instead of just revealing the behavior of individual abusers, the community is finally acknowledging this as a wide-reaching structural issue. And by “the community” we mostly mean cisgender men in the community, because people who aren’t cis men were already aware of the problem.

Many of the recent allegations follow the same pattern: Writers, artists, and editors using conventions to prey on young women, either for longterm coercive relationships or for hookups during professional networking events. This predatory behavior seems to be a common experience among women trying to break into the industry, and the alleged perpetrators included men who were outwardly feminist and supportive (like Warren Ellis) or made comics aimed at young women (like Spider-Gwen writer and artist Jason Latour and Robbi Rodriguez.) Usually, these men were protected either by their professional reputations or by progressive and/or female friends who were unwittingly used as human shields.

The American comics industry has long grappled with sexism, and in recent years there’s been a growing acknowledgment that the big publishers need to hire more inclusively at every level. But the past two weeks have shown how difficult—and perhaps impossible—this will be in the current climate. Most creators are freelancers, and in order to get hired, you need to network with the right people. Those “right people” are invariably middle-aged white men, some of whom are sexual predators. In turn, their friends and colleagues were either turning a blind eye to their abusive behavior or weren’t aware of it being a problem. This created an environment where women routinely felt unsafe at networking events, and couldn’t report harassment without professional repercussions.

It’s no coincidence that women often seem to find more success as solo and independent creators (for instance Raina Telgemeier or Ngozi Ukazu) than in the ecosystem of Marvel/DC/Image/Dark Horse, where you must collaborate with an extensive roster of other artists, writers, and editors to get ahead. How do you build those professional connections when you’re constantly navigating an obstacle course of sexual predators and misogynists?

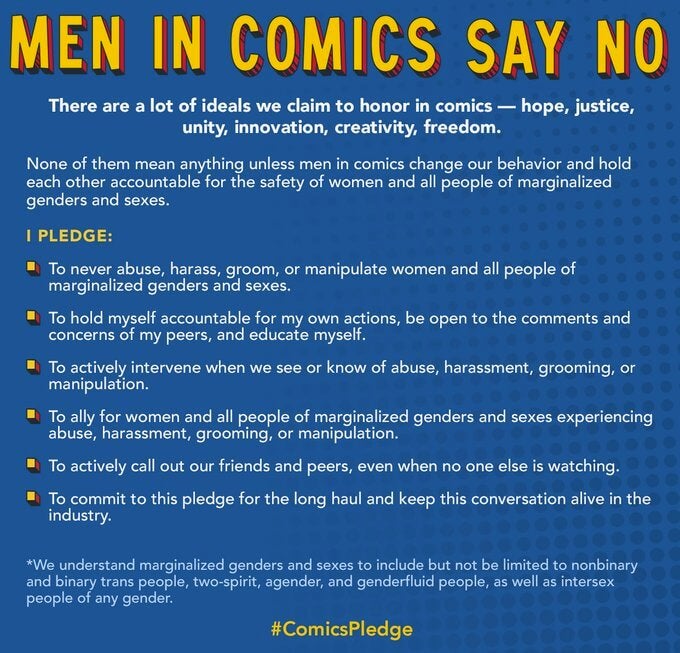

Some people are calling for an end to “barcon,” or socializing with alcohol at conventions. However, this is a divisive issue because it blames alcohol for what’s clearly a more complex cultural problem. In some cases, it seems like drinking was just used as an excuse for unprofessional conduct. A ban on alcohol would make convention parties more inclusive, but it wouldn’t prevent abusers stalking potential employees or grooming their victims online. Nor would it alter the power imbalance when industry insiders treat newcomers like sexual conquests instead of colleagues. Another possible solution has received a similarly mixed response: a #ComicsPledge encouraging respectful workplace conduct:

This pledge is well-meaning, and it suggests that more cis men are willing to acknowledge their own role in the industry’s toxic culture. However, it’s a little ridiculous to see them promise not to “abuse, harass or groom” anyone, when everyone already knew this behavior was wrong, and many of the alleged perpetrators portrayed themselves as “male feminists” who approached young women as mentors. It would indeed be helpful for men to hold their peers accountable, but there’s a limited amount of visible support even for this kind of performative hashtag activism. On social media, the conversation about sexual harassment is largely happening between people who are lower down on the industry foodchain, and who aren’t straight, cis men. The most vocal participants are women whose careers were already harmed by harassment and exclusion. By contrast, the top tier of creators and publishers have barely weighed in.

Acknowledging the problem and confronting harassers is the first step, but it’s hard to imagine much progress being made without internal investigations and policy changes at the big publishers, directly tackling their exclusionary work environments and history of sexual misconduct.

READ MORE: