Last year, the most successful celebrity in the world was a dead man. According to the Forbes Celebrities 100 List of top-earners for 2013, for the third time in the last five years, a deceased celebrity was the world’s biggest bread-winner. Between June 2012 and June 2013, Michael Jackson earned $160 million, and Madonna came in second with $125 million.

When Wikipedia recently published a report about traffic to the site, they revealed that the greatest spikes in their traffic in the last three years all followed celebrity deaths, specifically, Steve Jobs, Amy Winehouse and Whitney Houston. As Wikipedia quantified in data, the real value of a celebrity can’t be measured by the money they earn, but rather, should be calculated in terms of how much we want to remember them after they die. The greatest value is our emotional investment in dead celebrities. The surfeit of emotion and nostalgia they trigger makes them the ultimate clickbait.

Consider the recent deaths of James Garner and Joan Rivers. Their remembrances highlight the twin tendencies of our celebrity death culture. James Garner was popularly eulogized. And yet, most likely, he’ll soon slip from memory.

Why? Because some of you reading this are thinking: James Garner is dead? Others reading are thinking: Who’s James Garner? Either way, he’s already forgotten. You see, to millennials, if he’s remembered at all, it’s as (Old) Noah from The Notebook. For those of Gen X, he’s probably best known as Jim Rockford from The Rockford Files. Meanwhile, for Baby Boomers, he’s likely remembered as Bret Maverick from the uber-popular TV western of their youth.

But despite fans of multiple generations, James Garner passed away out of sight, out of mind. He was gone before he died. This was quite the opposite of the final days of Joan Rivers.

We talked about Joan Rivers right until her last days on Earth, and we’re still talking about her. Why? Because she understood us. Rivers knew it was vitally important to keep her ever-evolving face on TV screens at any cost. Her voice was always in the cultural conversation, agitating our eardrums, and in her last years, she was still showing up on the covers of supermarket tabloids. Thanks to her legions of fans, her last days provided a chance to build a ramp of goodwill that transformed her in our cultural memory and raised her from cosmetic surgery punchline to the saint of comedy — a role she’d formidably earned, as Howard Stern pointed out in her eulogy.

Of course, nothing is ever certain. Being in the public eye for their final days doesn’t guarantee or improve our memories of a celebrity. Consider the legendary radio DJ Casey Kasem. Casem’s strange last days devolved into a bizarre spectacle, one pock-marked with occasional stories of him appearing and disappearing all over the country as his family wrestled over control of his estate. Our positive memories were marred before he was dead. His end was so sad and surreal it defied comprehension. We didn’t want to focus on it, and consequently, we ignored it. Casey Kasem was set aside by the culture, and quickly forgotten. Collective memory is a mercurial thing. Like most of life, it depends on timing.

Some legends, like Lauren Bacall, are treated with respect in death. But the risk of so much pomp and circumstance is that their passing often feels overwhelmed by agenda and symbolism. In Bacall’s case, it was the end of an era, not just a woman. Just as she was attached to Humphrey Bogart in life, she was accompanied in death by a whole bygone culture.

The height of a celebrity’s popularity in life is never the best indicator of how they will be remembered in death. If that were true, Shirley Temple’s death would be a bigger story than Philip Seymour Hoffman’s. But emotion drives our online lives. That’s why the more modern actor, clearly one of the best of his generation, will be likely remembered more online than the biggest child star of all time. Another kid star, Mickey Rooney, looks to suffer the same fate. They hung around so long their stars dimmed, their fans died before they did, and everyone left forgot about them when they did finally die.

A similar fate will likely befall legends like Sid Caesar, Ruby Dee, Harold Ramis, Bob Hoskins, and possibly even Maya Angelou. All of their recent deaths were overshadowed by the surprising suicide of Robin Williams. There is no doubt he will be remembered. If you list all the aspects that lead to canonization on the Internet, the death of Robin Williams touches every single one.

When Robin Williams’ death was announced, it instantly went viral. Twitter and Facebook were the first places most people learned he’d died. As the news spread, it was followed by a multitude of reactions. Suicide? How could it be suicide? Is it because comedians are sad clowns? Had he always been depressed? Was he sick? Should we even be speculating?

To make sense of it all we relied on social media. Once his celebrity friends tweeted their remembrances and Billy Crystal offered his thoughts at the Emmys, after endless think-pieces were published, once the dark specter of depression was reconsidered, and after President Obama offered his condolences, it felt like all of our emotional bases were covered. We used the Internet to democratize the meaning of his death.

Sadly, this also meant Robin Williams’ death was manipulated to scam Facebook users, while cyberbullies, in the hours just after his passing, decided to traumatize his daughter, Zelda, on Twitter. (In a show of defiance, weeks later Zelda Williams vowed not to be bullied off the Internet.) Less publicly, there were the rest of us who just wanted to say what Robin Williams meant to us, how his life touched ours and we grasped for a sense of a personal yet public catharsis. That’s to be expected, though. These days, we often process our deepest emotions online.

A celebrity death can reach the rarefied heights of virality because it has everything. (Well, everything but sex. And sometimes, it has sex.)

The one person on the planet who best understands the ebb and flow of our emotional lives online is Neetzan Zimmerman, the former mastermind of viral content for Gawker. His technique for discovering virality before it happens is predicated on the power of one word: “This.” You’ve seen it in comments sections everywhere. That one syllable expresses the emotional connection we experience when online content plucks those ineffable yet all-important emotional chords inside you. It can be a simple as a laugh, or as profound as grief. A celebrity death is peak “this.” Somehow, their death is about us.

Many folks protest the Buzzfeedification of online content. They take umbrage with the Upworthiness of how our emotions get manipulated. In an essay in Esquire critical of this essential dilemma of virality, Luke O’Neil used the term “Big Viral” to describe the emotional fast food now being offered by our on online culture. He warned us that it seems unhealthy. Perhaps it is. At this point, no one knows. All anyone can say with any certainty is that emotional online content works. We want it.

On the Internet, to catch your attention, content must go deep and wide. It must cast the widest possible net and tantalize you with the deepest emotional hooks. The goal is instant emotional connection. Online media needs you to share content because that’s how the Internet makes money. Emotion = clicks. And clicks = paychecks. More than cat memes, dead celebrities hit that sweet spot. The ones we connect with most generate millions and millions of clicks, as we wrestle with what their death means for us, individually.

Jonathan Mahler of the New York Times offered this pithy insight into the death of Robin Williams, “In the age of the Internet everyone is an obituary writer.” With each Facebook post and every trending tweet, we culturally eulogize our dead celebrities. Because, never forget, they are ours. That’s the deal. They belong to us. Of course, sometimes, our celebrity worship can become a dangerous obsession. John Lennon comes to mind.

However, the more common variety of celebrity fandom, what most of us engage in, is a healthy form of pseudo-tribal identification. We use celebs like identity tags. They define us. Team Coco is the sort of cultural signifier that draws a line in the sand and declares which side you are on. When we lose our celebrities, we lose part of ourselves. We must process our grief or mourning. Indirectly, a beloved celebrity’s passing helps us confront the grim specter of Death up close and personal yet as a comfortable abstraction.

In “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” there is a perfect distillation of modern celebrity death culture. In that classic Western, John Ford considered the value of the hero, and offered this bit of dialogue from a journalist about our human preferences: “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” These days, our world moves at the speed of the Internet, we’re finding that facts don’t matter so much. Hoaxes and spoofs go viral, and those clicks make money the same as the truth. Economically, there’s no advantage valuing fact over fiction for an online media outlet. (Who has time for fact-checking?) Instead, the Internet prints and profits off the legends. We prefer those anyway.

Some suggest our celebrity death culture is a form of online hagiography—a way for us to lift revered cultural figures up to the status of online sainthood. But the Internet doesn’t seem interested in saint-making. Instead, it offers us countless avenues to tap into the Collective Unconscious. More than being sanctified with religious feeling, like a Jungian snowglobe, the Internet keeps close at hand our darling Rosebuds.

In ancient days, tribes drew constellations in the sky, connecting stars into stories, and doing so, they kept shining remembrances of their fallen heroes. Today, we select from our dead stars, connect them to our personal stories, and memorialize them. Like digital constellations cast high above us, they remain where we can always see them, and yet, they’re also there beneath our fingers, emotionally accessible with the press of a button—the ultimate clickbait.

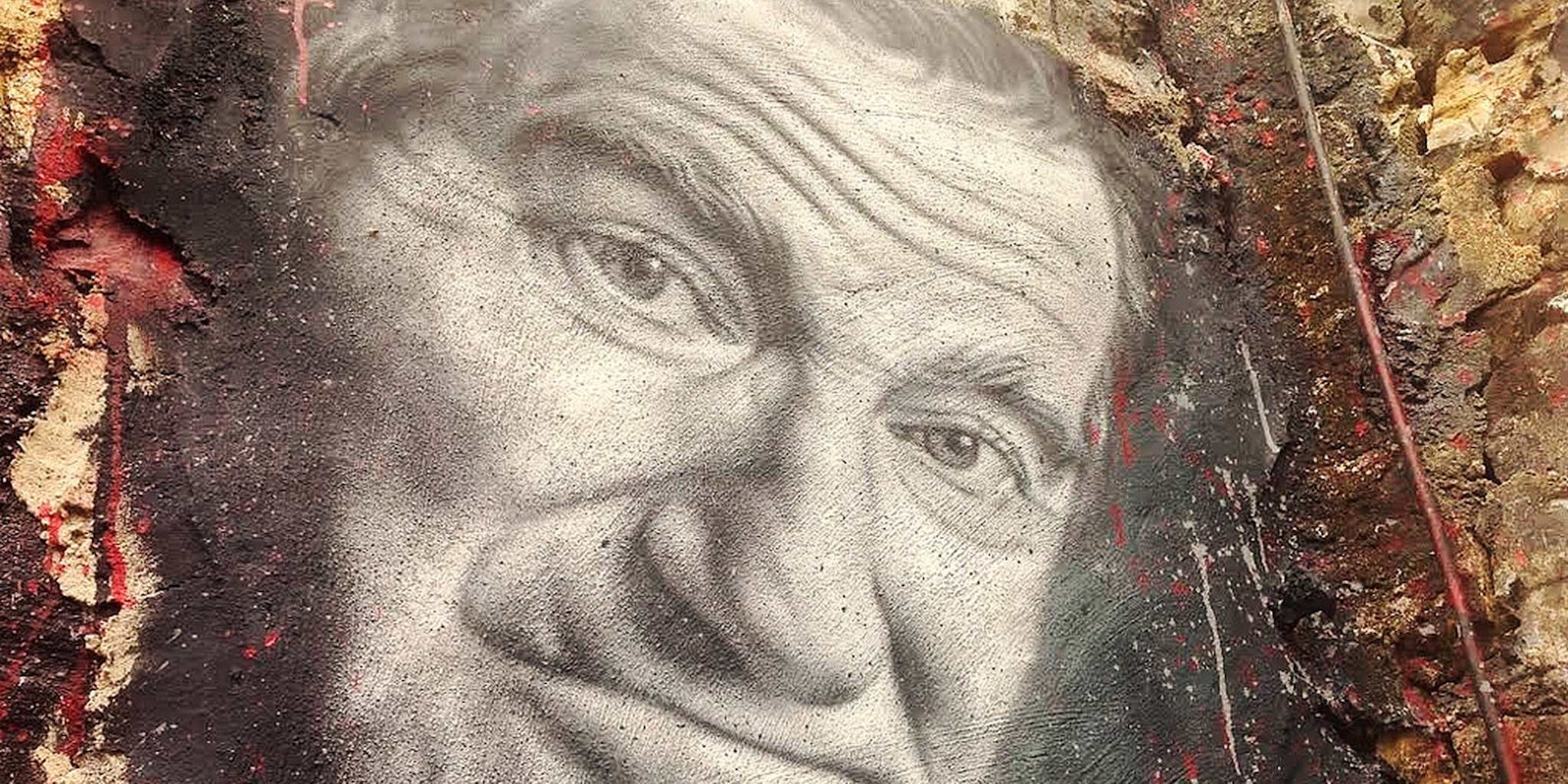

Photo via Thierry Ehrmann/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)