Sayori is my favorite character in the visual novel Doki Doki Literature Club. With short, messy hair and a sunny personality, fans regularly call her a “cinnamon bun.” Of course, there’s more to Sayori than just her cheery demeanor. I’m pretty sure she’s pansexual.

Early on in the game, Sayori turns to her fellow literature club member Natsuki and tells her, “everything you do is just as cute as you are.” She then “sidles up behind Natsuki” and “puts her hands on [Natsuki’s] shoulders.” Calling another girl “cute” is one thing, but touching her afterward? That’s some sapphic shit right there.

Theoretically, one could argue that Sayori is just trying to gain the protagonist’s attention by flirting with her friend. In most visual novels, that would be true. But there’s another moment toward the game’s later half—I’ll keep things spoiler-free—where it’s implied that gender isn’t a defining factor in how Sayori feels attraction.

For me, that recasts the entire shoulder-touching scene as undeniably queer. If Sayori can like girls, then her interaction with Natsuki must be more than just playful teasing. This explains why Sayori experiences depression, too. If she feels queer attraction in a world where women are largely expected to date men, she probably carries a lot of shame about her sexuality. No wonder why I like Sayori so much: she’s a lot like me.

My “Sayori is pansexual” theory is a “headcanon”. Fanlore describes the term as “a fan’s personal, idiosyncratic interpretation of canon, such as the backstory of a character, or the nature of relationships between characters.” In this case, I’m using material from Doki Doki Literature Club to suggest Sayori has a non-normative sexuality that plays out through the plot.

The term “headcanon” is somewhat new, but the issues it grapples with are not. Is the author really dead? Do we need to adhere strictly to the source text to understand a story? Does it matter what the writer thinks if it’s not what the reader sees? Personally, I’d argue it’s important to understand authorial intent in order to better understand what a story is trying to tell us about its characters and their motivations. But every book needs a reader. Without one, a novel is merely a bunch of symbols strung together on a couple of hundred sheets of dead trees. The way we interpret a story brings its characters to life.

As any English major will tell you, literary critics have long debated homoerotic desire in Shakespeare’s sonnets and plays, and some directors specifically go out of their way to interpret his work as queer. When the National Theatre put on its own rendition of Coriolanus with Tom Hiddleston in the titular role, one scene shows the Roman general sharing a kiss with his arch-nemesis, Volscian General Aufidius, who subsequently gushes about dreams where the two men are “unbuckling helms [and] fisting each other’s throat.” Step aside Sayori, that’s undeniably horny.

Granted, it’s unclear if Shakespeare actually wanted Aufidius and Coriolanus to have the hots for each other, but does it matter? When we let LGBTQ folks enjoy a story without forcing them to adhere to the author’s vision, we give them the freedom to explore their identities in art on their own terms. Not only is this empowering, but it can make queer people be seen in mediums like anime and gaming, where it’s traditionally hard to find yourself in your favorite worlds.

I’ve long known that podcaster Louise Ashley Yeo Payne loves queering stories and their characters, but I never understood why. When I chatted with her for this piece, she explained that the practice is about “mostly taking coding and making it explicit.”

“I’m not picking characters that are hard to queer. Just characters that should be queer from what already exists,” she told me. “It’s perhaps the need to queer the character in my own mind as much as possible before someone involved in the creation makes something that removes that from cannon possibility. So it is creating the representation that does not exist usually.”

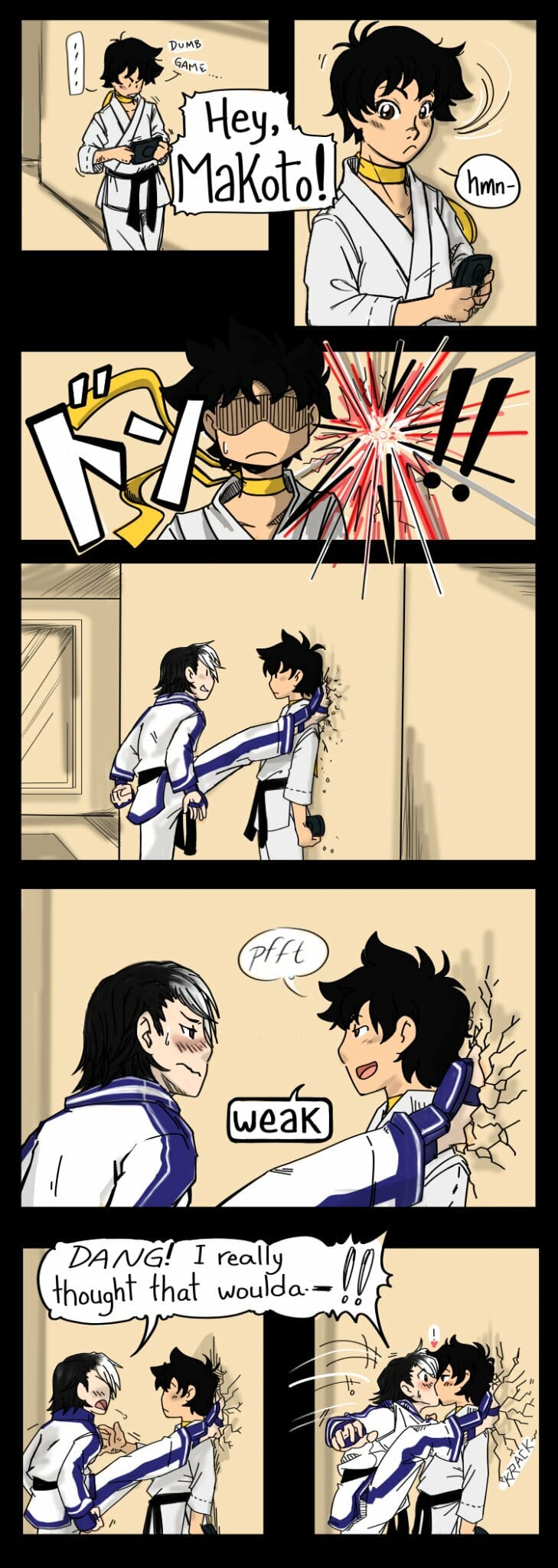

Payne points to Street Fighter’s Makoto, a Japanese karate master with short, black hair who wears a dōgi. She easily reads as a butch lesbian among fans, a point that resonates with Payne.

“Any queer woman would say that she’s coded queer, but she’s the sort of character that straight cis people would say is straight,” she told me.

This can be seen with other characters too. Take the immensely popular “Pharmercy” ship combining Overwatch’s Pharah and Mercy. There’s no specific lore that implies the two characters are a couple, but because their in-game character roles play well together—more specifically, Mercy as a healer hovering alongside Pharah firing rockets from midair—it only makes sense that the two women would be more than just colleagues.

aND HERE COMES MERCY WITH THE REZ!!!

— vero (@verororoni) August 13, 2016

this is a pic for my fav pharmercy fic check it out: https://t.co/GVhdmKj99X pic.twitter.com/RRFLLm6UZa

Y’all look what I bought bcuz I needed a new coin purse and I’m a FILTHY PHARMERCY SHIPPER(artist is giraffalopebuttons on Etsy!! Check out their stuff super cute!!) pic.twitter.com/0dV0XVpxaX

— Hex (@hexchu) January 18, 2018

D.Va is trans and gay

— What The MIRI? (@nyanilla_) January 21, 2018

Tracer is gay

Lucio is trans

Moira is NB

Pharah is trans and gay for Mercy

McCree is gay

Then there’s protagonist Shinji Ikari from the anime and manga series Neon Genesis Evangelion. Fans have long considered Shinji effeminate, with some queer folks considering him either bi or pansexual. This is partly due to his complex and intimate relationship with the equally androgynous Kaworu Nagisa, who also remains a fan favorite among gay, bi, and pan men.

https://twitter.com/MarcusLarry627/status/1054762961124892672

https://twitter.com/blankroomsoup/status/452605333056540672

Bowsette famously became a queer icon after trans fans called her transgender. The idea makes sense, given that Bowser’s transformation into Bowsette is literally a gender transition story: Bowser puts on the Super Crown and turns into an immensely adorable Peach/Bowser hybrid. Because Bowsette isn’t canon, trans fans have even more freedom to interpret her however they want.

https://twitter.com/jaskerart/status/1045180039149408256

Another bowsette comic. She’s a trans lesbian icon, do not take her away.

— fake gamer girl jamiee (@fakegamercomics) January 21, 2019

For more comics, and community, check out https://t.co/aLzifGoBYC <3 pic.twitter.com/WMN71YU2LT

https://twitter.com/traaaaaaannnnns/status/1077008277920247810

While each of these characters represents a different part of queerness, they all fall back on the same idea: marginalized fans build a sense of community and visibility by seeing themselves in their favorite characters. It’s a DIY approach to being LGBTQ in a world where real, radical visibility is rarely available.

“I think I would be too lazy to queer characters in media I liked if genre fiction was more diverse and representative,” Payne told me, later adding, “[I]n this we can have two people who are queer, who are into each other have a fun time.”

We all create our own relationships with our favorite stories, characters, and themes—so when queer people do it, let us have some fun. We deserve it.

READ MORE: