Ex Machina is already being hailed as one of the most interesting sci-fi movies of the year, a tense thriller about artificial intelligence from the writer of 28 Days Later and Sunshine.

The action takes place in the claustrophobic and secluded home of a Zuckerberg-esque tech billionaire, Nathan (Oscar Isaac), who brings in a low-level employee named Caleb (Domnhall Gleeson) to help test a top-secret project: a prototype A.I.

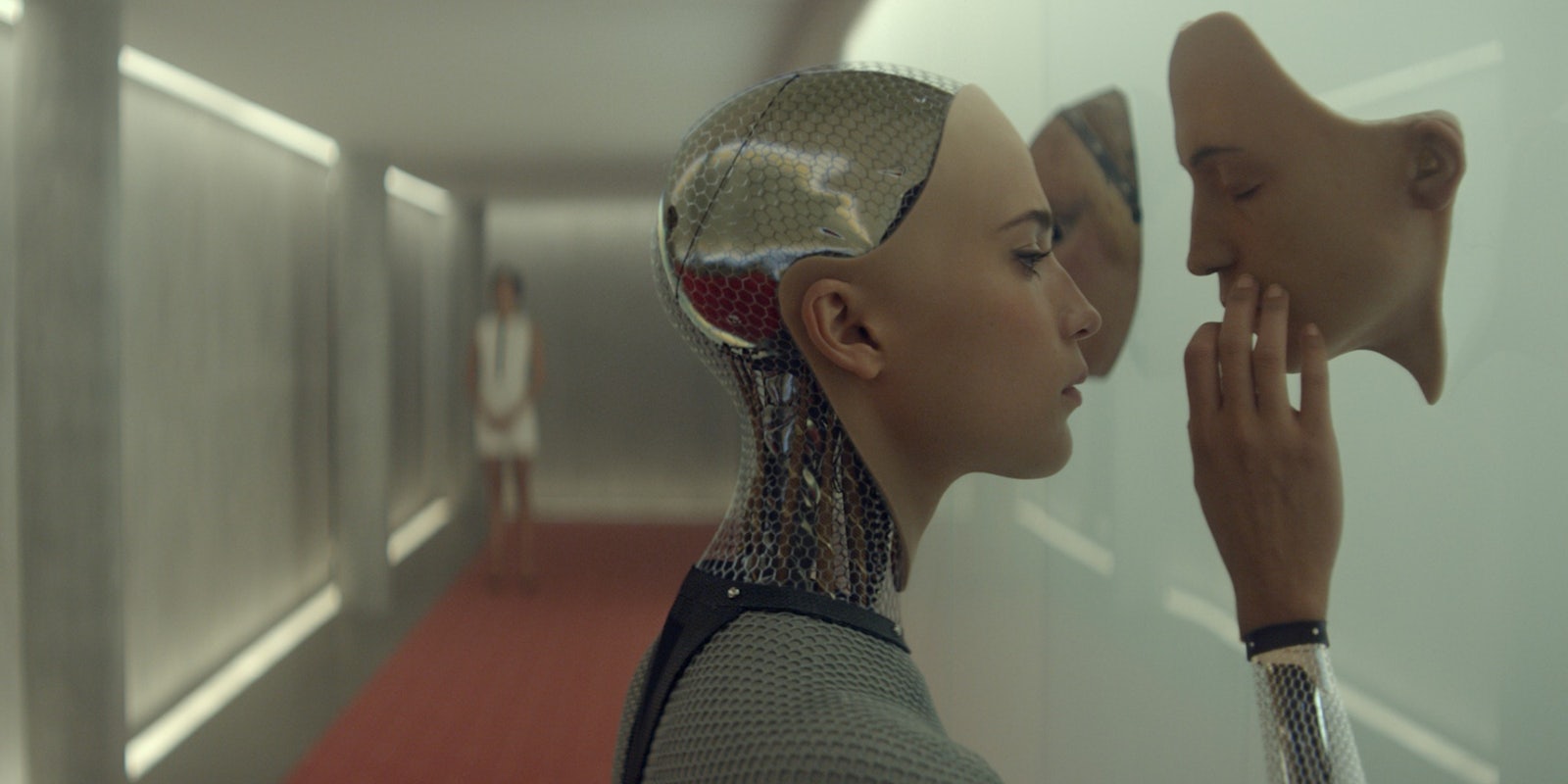

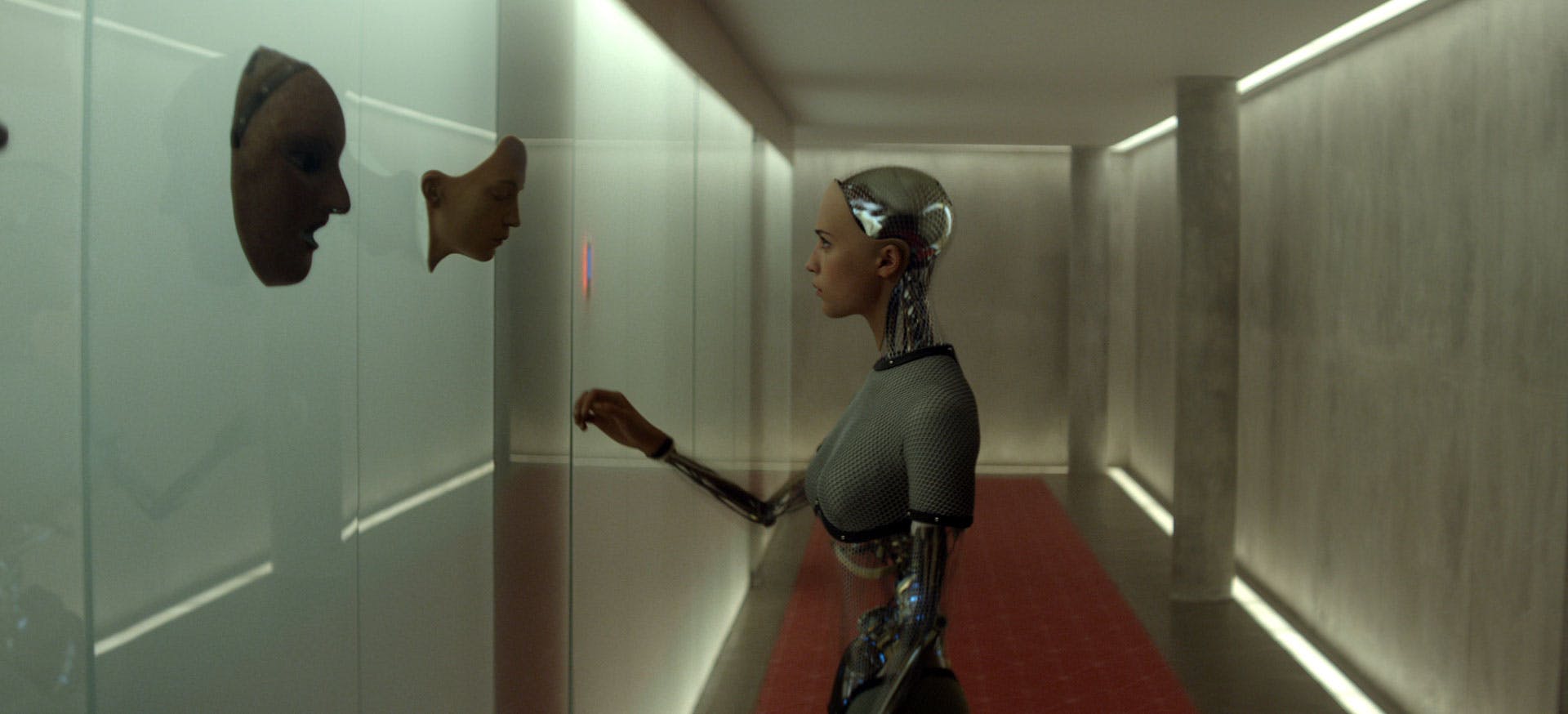

This A.I. is introduced as Ava (Alicia Vikander), a humanoid robot with the face of a young woman. Caleb’s job is to determine whether she truly possesses human-like artificial intelligence, based on whether they can relate to one another on an emotional level.

Rather than playing off Hollywood stereotypes of sexy female robots, Ex Machina invites more complex questions about artificial intelligence and gender, with Ava’s sexuality (or lack thereof) often saying as much about Nathan as it does about her. As a manipulative and aggressively macho genius who lives by himself in the middle of nowhere, Nathan holds a disturbing amount of power over everyone else in the house.

Here’s an exclusive clip of the film, which is playing in theaters now.

As we learned when speaking to writer/director Alex Garland, Ex Machina has provoked a wide range of interpretations from its audience—although, we should point out, almost unanimously positive reviews.

How were you influenced by other depictions of A.I. in science fiction? Were there any tropes you were making an effort to avoid?

Alex Garland: Not exactly. I mean, I was very aware of other A.I.s. Sometimes it was useful, like I’d know that people were likely to have seen Blade Runner, which would lead them to suspect that one of the two male characters was A.I. or something like that, which I could use for misdirection.

There are also a lot of real-life influences, like the sci-fi elements being grounded in concerns about surveillance and the power of companies like Google. It made me wonder in terms of real-life social influences, how much you were inspired by geek culture? It felt like Nathan and Caleb represented these two sides of the nerd stereotype: the socially awkward guy and the aggressive, macho brogrammer.

I think this is similar to the previous question in that I didn’t localize it to what you just described in geek culture. I think you could broaden it out to all kinds of male culture, in terms of the way men interact with each other and the way different guys will find different ways of competing and playing games. Trying to gain an upper hand, that kind of thing.

In a way I’m not familiar enough, I don’t have a clear idea in my head of what geek culture is, to be specific in that kind of way.

So would you say it’s more a critique of toxic macho culture?

I think there is a criticism within it… but it’s not purely aimed at them. There’s also a criticism aimed at the gentler guy as well, who’s not particularly macho.

A lot of the film was to do with raising questions about certain kinds of behavior. Some of it might be to do with people, some of it might be to do with theory of mind, or might be to do with science… Just saying, “This is interesting,” not, “This is interesting and here is the correct way of looking at it or the correct answer,” but just presenting it as an interesting conversation.

“We talk a lot about objectification, but actually more often what humans do is they de-objectify things.”

I think some of the questions raised in the film, I personally, privately have quite strong visions about… and there’s other questions in the film that I really don’t know the answer to, and I’m just interested in thinking about them, and hope that other people are interested too.

I think that ambiguity worked quite well. When I was researching the movie, there were a lot of quite disparate reactions and interpretations.

Yeah, that’s exactly right. And I think, often those things… when you get two very strongly held, conflicting positions on exactly the same thing, that must imply to a certain extent that the reaction is substantially to do with the person having the reaction rather than the thing itself. So there’s a lot of room for subjective response, I would say. Partly because the film is not, in a signposted way, saying “This is where the film stands on this particular issue.”

It does raise a lot of questions about gender, especially Ava’s. The big question is, how do you give a robot gender? I was wondering about the way her visual appearance was designed, how did you decide what Ava would look like, with the Uncanny Valley situation and Alicia Vikander’s performance?

My feeling was, the hardest thing was essentially to stop people automatically providing a gender, and beyond that just providing human-like qualities. Because we talk a lot about objectification, but actually more often what humans do is they de-objectify things. They attribute sentient qualities to things that don’t actually have them, and so the initial path with Ava was to make her seem like a machine. That your first impression was not, “This is a young woman who is dressed up like a robot,” but this is unambiguously a machine—and therefore in some respects doesn’t have a gender.

There’s that scene where you see her putting on the clothes, and that’s kind of the reversal [of that process]. I’d be interested to hear the way you worked with the costume designer, Sammy Sheldon. Did you have a clear visual idea in your head about what the characters would look like?

That’s got a sort of odd connection with a broader philosophy of film seen from my point of view. Although I did speak a lot to Sammy about all sorts of things, such as what to do with Ava’s robotic question, I didn’t actually talk to Sammy much about what any of the characters were wearing. Because to me that was part of a conversation between the actor that is inhabiting the character and Sammy. So the primary exchange there would’ve been between Alicia and Sammy.

To an extent, there was a conversation that began with the art director, Michelle Day, who came up with a sort of theory of the way we could hide Ava’s form using stockings and long-sleeved clothes, without making it look too coy. Essentially, without making it look like we’re deliberately trying to cover her robot structure… whilst also covering her robot structure.

Thinking about the visual aspects of the film… The sets are very simple, because you’re only filming in this one house. To what extent did budget influence the film? I read that you purposefully stuck with a relatively low budget. Was that influenced by your experiences on bigger movies like Dredd?

Dredd and Sunshine were there in my mind—there’s a lot of parallels between Sunshine and Ex Machina, actually.

One of the things I’d left Sunshine feeling very strongly about was that we had too much money, or we should’ve made it for less money. And underneath all of that is something to do with an anxiety about creative freedom, the kind of pressures that come with money.

“One of the things I’d left Sunshine feeling very strongly about was that we had too much money.”

In the end, I’d say that we had exactly the right amount of money that we needed. What actually happened with Ex Machina was that when I wrote it, I imagined it as a kind of $4 million movie, because I thought we were going to raise the money from this U.K. outfit, Film4.

When the producers saw the script, they said, “We actually think there is a way we can raise more money, and keep the script exactly as it is. And in fact to do this, you’re gonna need more money.” And so what happened was, they said, “What we need to do this to exactly the level it’s written is $15 million, so we’re gonna try and get $15 million.” So, weirdly, in the end we had more money than I thought we budgeted.

Do you think your next work is going to be another low-budget sci-fi? It sounds like you had a really good experience with this one. Or do you think you’ll be moving onto something different next time round?

I had a very good experience, a sort of holistically good experience I think. It was perfect in every regard I could hope for.

The trick for me is, the question I’m asking myself is, can I get more money and hold onto the kind of freedoms that we had on Ex Machina? And I really don’t know the answer to that. I literally don’t know the answer to that. But we are gonna try. We’ve got a proposal that we’re submitting now, in fact I’m meeting someone in a couple of days to try and secure the finance. That is, at the moment, budgeted at roughly twice the budget Ex Machina. In real terms it would be slightly more, but we get a tax break for shooting in the U.K. But basically we’re looking at around about twice the budget.

So you’re probably not going to be hopping on the blockbuster sci-fi bandwagon anytime soon?

No, no, no. I doubt that very much. I’ve been working in films for 15 years now, and I’ve got a pretty clear sense that whatever I do, it doesn’t seem to ever hit a kind of mainstream sensibility very effectively. You know, I’d love Dredd to have been a big movie, but whatever else it was, it’s definitely not a big movie. So I have to sort of pay attention to that.

This is probably a question you’ve had before, but could you share a bit of the background of Oscar Isaac’s dance scene? I’d like to hear how that came about.

There were two main reasons. One was actually to do with a film I’d worked on before Dredd called Never Let Me Go, which also has some similarities Ex Machina.

Never Let Me Go is a film I like very much and I’m very proud of it and all that kind of thing, but I also felt it had a kind of… like a monotone. That bothered me. There weren’t enough tonal spikes. So in Ex Machina I was always hoping for ways to be jagged. It’s got quite a zen vibe, and a zen vibe smothers everything if you’re not careful, so I wanted to be disruptive.

The other thing about it was it just struck me as a really strange, left-field way for one guy to exert a kind of pressure on the other one, while also saying something oddly despairing about the state he must have been in to have spent presumably months finely honing these solitary disco routines between him and a machine.

This interview has been edited for length.

Photo via exmachinamovie