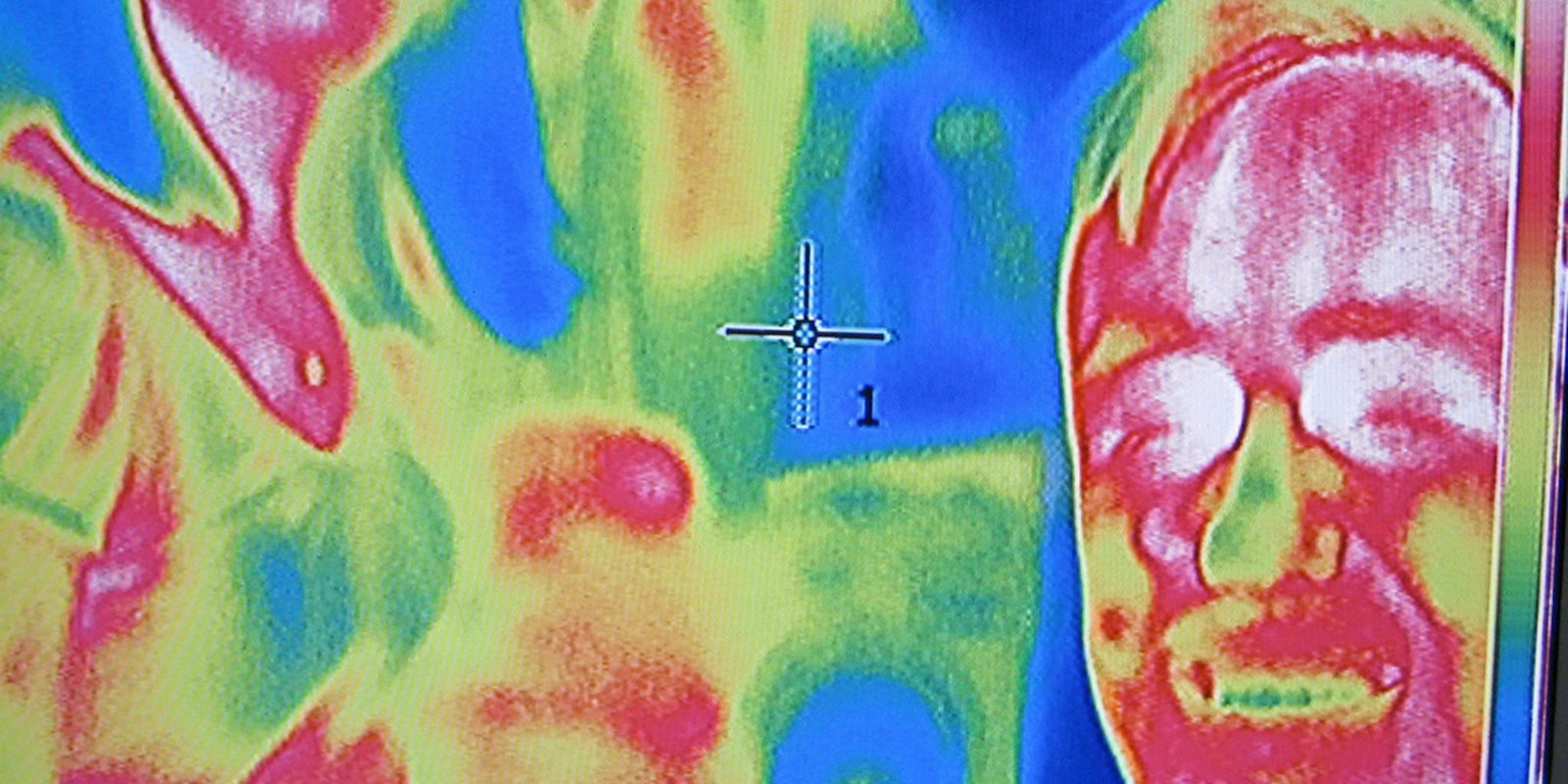

The surveillance cameras of the future don’t need light to see your face.

German computer scientists Saquib Sarfraz and Rainer Stiefelhagen have developed a thermal imaging system that can identify individuals by comparing their facial heat signatures to standard daylight pictures of their faces.

The system “sees” in relatively nondescript colorizations to indicate the surface temperature of whatever enters its field of vision, but its software processes these images so well as to be able to identify who it sees.

The researchers’ facial recognition system is built on a neural network, which means its software carries out tasks in a way that imitates the human brain. It’s a fast, efficient way to do this type of work: In testing, it successfully matched two images from among a set of 4,585 in a faster-than-a-blink time of 35 milliseconds. MIT Technology Review reports that “its accuracy is just over 80 percent when it has a wide range of visible light images to compare the thermal image against. The one-to-one comparison accuracy is just 55 percent, however.”

Startup Policy Lab’s Director of Data & Privacy Timothy Yim suggests this technology might deserve more warning bells than “hey, that’s cool” accolades. “First, the technology itself is still being refined,” he told the Daily Dot. “The possibility of false positives, especially given the criminal security context to which thermal facial recognition likely will be applied, could have grave consequences.”

Yim hypothesized a potentially treacherous future environment in which thermal imaging data is collected on a mass scale, as the NSA does with its notorious phone call metadata collection program. “Coupled with known and yet-to-be discovered correlations drawn from that thermal data, a host of once private information could be laid bare,” he said. “For example, a man leaving a meeting with his boss two degrees warmer than he entered might be presumed incensed and dinged for insubordination. Or perhaps, thermal data might inadvertently reveal that a young woman and employee is pregnant before she herself has revealed that information.”

If this technology were to be deployed across the United States in public spaces today, it would be legally viable. “If I had this tech and used it on a public street, depending on the state, it would be difficult to bring a privacy action against it,” said Jeffrey Vagle, a lecturer in law and executive director of the Center for Technology, Innovation and Competition at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. “This doesn’t take into account the limitless databases that might be storing this data for use later. That changes the calculus.” He likened it to license plate readers, a law enforcement technology that has “a chilling effect on basic civil liberties and the ability to travel freely.”

This experimental heat vision surveillance and identification system only works by maintaining a large collection of headshots to compare its thermal scans against. Its value and utility varies directly with the size of such a collection—more photos means a increased likelihood of a match. “Given enough [thermal image] correlations, we can derive lots more correlations,” Yim told us. “If thermal data and sensors become more widespread, what we once thought was private info could become public.”

Just 12 to 15 years ago, the thought of using one’s real name on the Internet would have been met with grave security concerns. The thought of meeting someone in real life based on Internet-only socialization was laughable for the same reasons. Nowadays, we regularly send our credit card numbers and home addresses over the Internet, and apps like Tinder and Airbnb suggest that its ability to connect real people in the real world is one of its most valuable applications. The nature of what we consider to be private information is changing, and it will only be more difficult to maintain privacy in the future.

After all, it’s easier to change your name than your heat signature.

H/T BGR | Photo via Steven Jurvetson/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)