Before Ross William Ulbricht decided he wanted to change the world, he studied physics at the University of Texas at Dallas, worked as a peer-reviewed research scientist, and finally, served as CEO of a small online used book store called Good Wagon Books. In his spare time, he enjoyed the occasional psychotropic drug.

Then, in 2010, Ulbright wrote on LinkedIn that he wanted to “use economic theory as a means to abolish the use of coercion and aggression amongst mankind.”

I am creating an economic simulation to give people a first-hand experience of what it would be like to live in a world without the systemic use of force.

In May, Ulbricht’s LinkedIn resumé indicates he left his job at Good Wagon Books. What did he do next? His roommates, family, and even his best friends all say they had no idea how he made a living—except that it was online. His LinkedIn profile remained unchanged. But if allegations in a federal indictment filed last week prove true, Ulbricht was very busy.

MORE: The rise and fall of Silk Road’s heroin kingpin

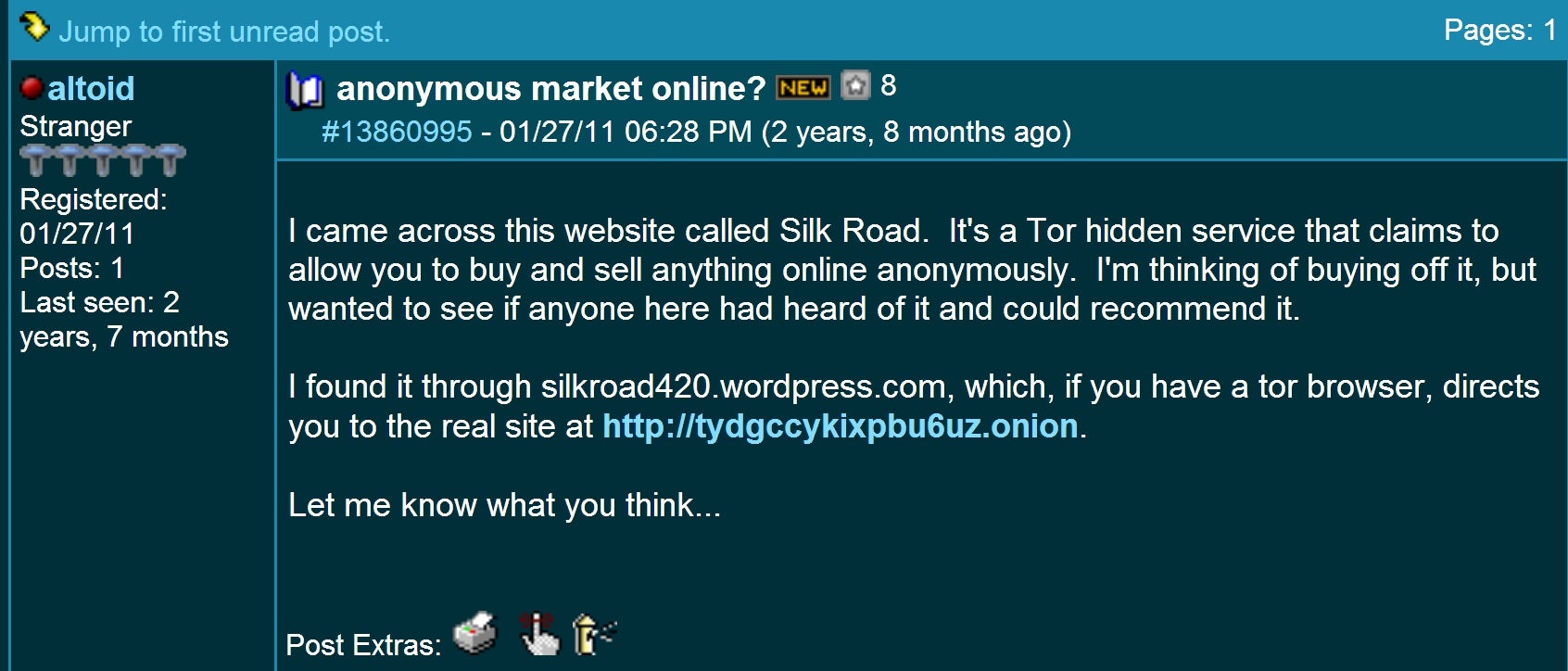

On Jan. 27, 2011, Ulbricht anonymously unveiled his masterpiece to the world. In a brief post on psychedelic mushroom site Shroomery.org, he posed as an anonymous netizen who simply stumbled across a new website. It was called Silk Road. He asked for feedback.

The immediate response was skepticism. Ulbricht may have thought that his little marketing ploy had failed, so he wrote about Silk Road on the BitcoinTalk.org forum two days later with a very similar post. BitcoinTalk readers were interested immediately.

In fact, the initial Shroomery post had actually succeeded wildly. Over the next few months, Silk Road became genuinely popular among Shroomery users as word passed from person to person: “Yes, you really can buy drugs safely online.”

Others had come before the Silk Road. From the 1980s to the 1990s, Usenet groups, chat rooms, and markets like the Hive ushered in a revolution in the way the world discussed, shared knowledge about, and traded illegal drugs. Just prior to Silk Road’s launch, two sites—the Open Vendor Database (OVDB) and the Farmer’s Market—specialized in selling drugs online.

Like the Silk Road, these older markets used digital currencies—electronic money that acts as an alternative to dollars and euros—such as e-gold, Pecunix, and Liberty Reserve. Many of them even used Western Union and Paypal to handle transactions. But the majority of earlier markets didn’t even employ anonymizing technology. They largely existed in plain sight, apparently hoping that law enforcement would just miss them in the boundless landscape of cyberspace. They still made good money, however: The demand for online drugs has always been huge, and these flawed markets were scraping off a small piece of the pie. No one had really exploited the market.

Silk Road was different. It was the first market to leverage the anonymizing power of the browser Tor, the peer-to-peer crypto-currency Bitcoin, and the encryption program known as Pretty Good Privacy. Silk Road quickly attracted attention as the safest place to buy drugs online. It was the first website to model itself after the easy-to-use commerce giant Amazon.com, a comparison made by Ulbricht himself in early promotional posts.

Silk Road was different. It was the first market to leverage the anonymizing power of the browser Tor, the peer-to-peer crypto-currency Bitcoin, and the encryption program known as Pretty Good Privacy. Silk Road quickly attracted attention as the safest place to buy drugs online. It was the first website to model itself after the easy-to-use commerce giant Amazon.com, a comparison made by Ulbricht himself in early promotional posts.

By May 2011, Silk Road was home to hundreds of users selling and buying a growing variety of drugs across the world.

“Knowledge about how to access the website spread only by word of mouth,” Dread Pirate Roberts later wrote, “and the only way to find out about it was if you knew a guy who knew a guy who knew how to get into the site.”

At this early point, “everyone was sophisticated,” a money launderer on Silk Road who goes by the handle StExo told the Daily Dot. “Everyone was safe, everyone was cautious. There were no guides because the only people who could access such things generally were the very security-aware people.”

Of course, that would all change. On June 1, 2011, at the too-good-to-be-coincidental time of 4:20pm, Gawker’s Adrian Chen revealed the existence of Silk Road to the world.

“Silk Road was a godsend for me,” a user named SexyWax recently told the Daily Dot. “I was unemployed and miserable at the time… I had thoughts of suicide often. I was just a customer in early 2011. After the Gawker article came out, I began thinking about being a vendor.”

Before Chen’s article, Silk Road had hundreds of users. That soon jumped an order of magnitude, to over 10,000. That crush of visitors occasionally brought down the site’s servers. And it also encouraged scammers, ready to prey on curious newbies who, more often than not, didn’t know how to adequately protect their anonymity and money.

A still-volatile Bitcoin made doing business even riskier. Between June and November 2011, the digital currency’s value rose to $31 then plummeted to $2 as it adjusted to the Silk Road rush, making it difficult for sellers to make money. Security difficulties facing the Web’s largest Bitcoin exchange didn’t make business any easier.

To help balance against Bitcoin’s volatility, Dread Pirate Roberts introduced a “hedged escrow” option buyers and sellers in May 2011. For the rest of Silk Road’s lifespan, bitcoins were converted into U.S. dollars after a purchase, held in an escrow, and then changed back as the transaction was finalized, thus shielding both sides significantly from whatever currency volatility may creep up.

Curiosity soon turned into cash. New users made orders in droves and turned Silk Road into a singularly successful enterprise. Bitcoin launched on an upward trajectory as it crept toward stability.

Days after the Gawker article, American Senators Charles Schumer and Joe Manchin wrote letters to Attorney General Eric Holder and the Drug Enforcement Administration urging them to “take immediate action and shut down the Silk Road network.” Just a week after being revealed to the world, the Silk Road brand was everywhere.

“That was great for business,” one Silk Road vendor told the Daily Dot.

The site became so popular that on July 1, 2011, Roberts began to charge 10 bitcoins to become a seller. That price would only go up.

For his part, Ulbricht seemed to be active all over the place. On Oct. 11, 2011, Altoid—the same user who originally advertised Silk Road—posted a wanted ad on BitcoinTalk looking for “an IT pro in the Bitcoin community.”

He asked interested parties to email “rossulbricht at gmail dot com,” a Google account with mountains of identifying information on it.

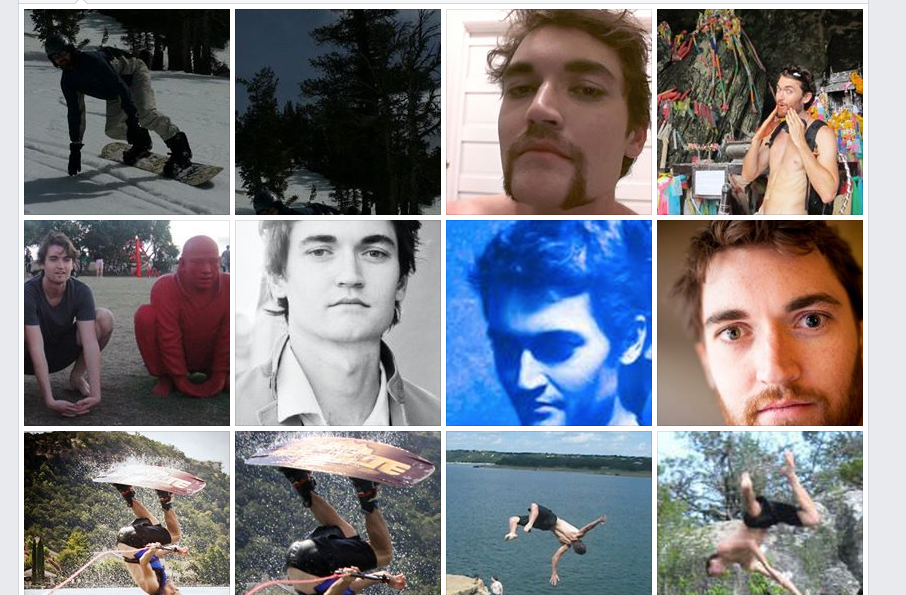

Photos via Ross Ulbricht/Facebook (remix by Gwern)

“He is utterly brilliant,” someone purporting to be Ulbricht’s friend recently wrote on Reddit.

You know how people in college like to think they’re being all intellectual and have ‘deep’ conversations? Well, Ross was for real. He’d lose everyone in the conversation after a few minutes, he was just thinking through things at a level so profoundly different than the rest of us.

As Dread Pirate Roberts, a name he allegedly adopted in February 2012, Ulbricht became a charismatic preacher with an audience of thousands.

“Here at Silk Road, we recognize the smallest minority of all, YOU!,” he wrote. “Every person is unique, and their human rights are more important than any lofty goal, any mission, or any program. An individual’s rights ARE the goal, ARE the mission, ARE the program.”

Roberts wrote a book’s worth of essays preaching anti-state libertarianism. “The drug war is an acute symptom of a deeper problem,” he wrote. “That problem is the state.”

Silk Road is about something much bigger than thumbing your nose at the man and getting your drugs anyway. It’s about taking back our liberty and our dignity and demanding justice.

In his days as a student, Ross Ulbricht campaigned for Ron Paul and donated to his campaign. He professed a love of Austrian economics and libertarian politics. If he hadn’t launched the Deep Web’s most popular black market, as the FBI alleges, Ulbricht might have had a career in politics ahead of him. He certainly knew how to get adoring masses hanging on his every word.

But not everyone loved Dread Pirate Roberts.

In February 2012, a year after it launched, the Silk Road spun off a subsidiary market called the Armory. A fierce debate started up about the morality of selling weapons. Drugs are one thing—everyone on Silk Road was united in their love of legalization—but guns forced a wedge between users.

In February 2012, a year after it launched, the Silk Road spun off a subsidiary market called the Armory. A fierce debate started up about the morality of selling weapons. Drugs are one thing—everyone on Silk Road was united in their love of legalization—but guns forced a wedge between users.

Roberts wrote several essays defending the new weapons market and its merits as the Armory tried to establish itself. Ultimately, it failed after just six months due to slow business.

While all sorts of drugs and, for a time, guns have been seen on Silk Road, there was more to the market. You could also buy forged documents, MacBooks, cellphone jammers or imitation designer fashion. There were some limits, however.

“Practically speaking, there are many powerful adversaries of Silk Road and if we are to survive, we must not take them all on at once,” reads the Silk Road Seller’s Guide. “Do not list anything who’s [sic] purpose is to harm or defraud, such as stolen items or info, stolen credit cards, counterfeit currency, personal info, assassinations, and weapons of any kind. Do not list anything related to pedophilia.”

All the above—from child pornography to weapons to stolen credit cards—are easily available in other marketplaces around the Web.

Many people have taken Roberts’s self-imposed regulations to mean that he wanted to run a market with a conscience. While that’s certainly true to some extent, it’s also worth noting that Roberts was a pragmatist. He knew that selling millions of dollars worth of drugs made enough enemies. Adding counterfeiting or credit card fraud only put more targets on his back.

And, as Ulbricht would allegedly find out, the Deep Web assassination market has always been full of frauds. Keeping supposed killers-for-hire off Silk Road had the extra benefit of keeping scams at bay.

For all the impressive technical skill it takes to set up an operation like Silk Road, Roberts obviously needed help.

“How can I connect to a Tor hidden service using curl in PHP?” an account named Ross Ulbricht wrote on StackExchange.com in March 2012. The code described in the question matches closely to the one code used on Silk Road.

The FBI alleges that a minute after posting the question, Ulbricht changed his account name to the more anonymous “frosty.” Later, he changed the account’s email from the Ulbricht GMail account to frosty@frosty.com, a fake address. It looks like Ulbricht was actually crowdsourcing tech support for Silk Road. But in the process, he was leaving a trail for the FBI.

In August 2012, Roberts announced that he was hiring a new Unix administrator with an attention-grabbing $1,000 referral prize.

Roberts explained that the new hire would essentially be an advisor without direct access to the server. Some enthusiastic fans said they passed the wanted ad onto qualified friends from heavyweight tech firms such as Cisco. Roberts said he was blown away by the caliber of applicants.

However, several top vendors lost significant confidence in Roberts on that day.

“He had severe limitations,” said one anonymous vendor. “He grossly overestimated his own skills.”

Users wondered if it was careless for Roberts to hire someone he didn’t know and trust. What if the guy was actually an undercover cop?

To celebrate the stoner holiday 4/20, the Silk Road held a big sale. In the excitement that followed, Tony76—likely the biggest vendor on Silk Road at this point—decided to offer holiday discounts on MDMA, heroin, cocaine, LSD, and ketamine to customers around the world. New customers flooded in to make their first purchase off of Tony76, the most trusted name in online drugs.

The account had originally been registered in January 2012. Within a week, he was selling heroin from Canada, and good reviews rolled in quickly, provoking excitement and even a little hopeful skepticism. Within three months, Tony76 had sold a wide selection of drugs to over 500 almost exclusively happy customers.

Tony began to require customers to “finalize early.” Instead of using Silk Road’s trusted escrow system, customers had to forward Bitcoins to Tony76 immediately. He needed to do this in order to stop scammers, who’d been demanding refunds and giving him bad reviews.

The holiday came and went. At first, great reviews of Tony76’s trademark high-quality ecstasy came in. But soon, negative reviews began to surface. Packages were late and Tony76 wasn’t responding to messages.

It soon became clear that virtually no one was receiving packages ordered during Tony76’s 4/20 sale.

Within a week of 4/20, users accused Tony76 of being a scam artist who just picked up and left with all the money he’d made from the sale. His defenders said that Tony76 had proven himself trustworthy already and that his doubters were “full of shit.”

Was Tony a cop? Was he a scammer? Was he arrested? How could anyone at Silk Road ever know?

Estimates of the total amount stolen ranged from $50,000 to $100,000. For weeks, Tony76’s biggest fans kept defending him. He was never heard from again.

While multiple Deep Web black markets boomed to million-dollar businesses, police around the world were not idle.

Silk Road’s biggest black market rival was busted in April 2012. The Farmer’s Market was founded in January 2007 as a normal website and later moved to Tor. With thousands of customers around the world, the Farmer’s Market was doing $1 million in sales. Instead of Bitcoin, TFM used services like PayPal and Western Union. And instead of the fully anonymous TorMail, TFM used the encrypted email service Hushmail, which eventually handed their communications over to the police.

Many Silk Roaders shrugged off the bust, believing that the Farmer’s Market was inherently less secure because of those operational differences.

The first confirmed arrest of a Silk Road user took place in July. Australian Paul Leslie Howard pleaded guilty to two charges of “importing a marketable quantity of a border-controlled drug—which carries a maximum of 25 years jail—and to trafficking controlled drugs and possessing 32 controlled weapons.

Howard’s arrest highlighted the “Australian problem.” Because Australia is an island and its border control is especially strict, mailing contraband is always more risky than to most other locales. Many vendors across various Deep Web black markets charge extra for Oz-bound products, if they allow the purchases at all.

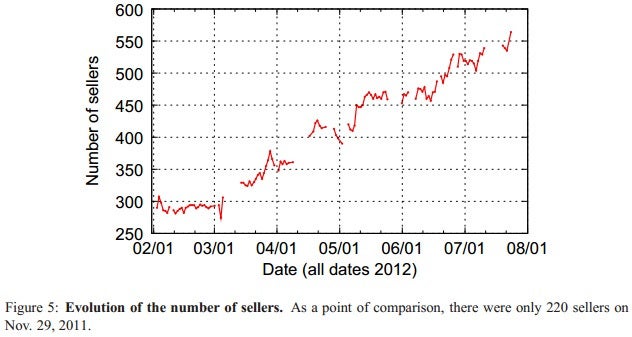

Silk Road marched on. By August 2012, a Carnegie Mellon study by Nicolas Christin estimated the marketplace was doing approximately $22 million in sales in six months. In 2013, he adjusted his estimates to $30-$40 million.

At the time, numerous vendors scoffed at that number as too low. Today, the FBI alleges that the numbers are many times higher.

Silk Road boasted at least 220 distinct vendors in February 2012. It grew to 564 in July 2012.

Image via Nicolas Cristin

Even amidst a booming population, there was an almost palpable sense of camaraderie in the Silk Road community. Many more knowledgeable users strived to help new users whose safety was put at risk by inexperience or downright incompetence.

“It’s a shame we’re all outlaws,” oldtoby wrote. “I’d enjoy grabbing a stout with some [Silk Road] forum folk sometime.”

By November 2012, Silk Road was in “uncharted territory” in terms of users, Roberts wrote.

On Nov. 8, Roberts announced the first major cyberattack on Silk Road. A hacker had changed product images, added a “quick buy” option that included a Bitcoin address, removed shipping options, and then made it impossible to place a legitimate order for nearly a week.

Around that time, several top Silk Road vendors had their accounts drained of all their money in a single day. Roberts attempted to keep the stealthy heist quiet and clashed with a moderator who spoke about it in public. The moderator was removed from staff.

Several users wondered if the hacker was the new proud owner of Silk Road’s entire database. If so, would Roberts be honest about it? Could he even know for sure?

Despite the attacks, Silk Road felt near unstoppable to many of its users. The market was a mainstream smash. Teenagers regularly posted about their Silk Road deals on blogs. The unofficial Silk Road Facebook page grew to 2,000 fans. A major MDMA bust at Tulane University only seemed to confirm Silk Road’s ubiquity. The black market’s name could be heard in cities around the world.

Major scams popped up occasionally. In February 2013, an Australian MDMA vendor named EnterTheMatrix conned customers out of tens of thousands of dollars in a Tony76-style sale. Most Silk Roaders—even the angry ones who lost out—shrugged it off as the cost of business.

Silk Road’s unprecedented growth meant that people who were utterly incompetent began to do business there, too. Some vendors used regular email services such as Gmail, and buyers shared tracking numbers on packages. Some of the wealthiest drug dealers on the site didn’t use encryption. When one vendor uploaded a picture of heroin, he didn’t remove the photo’s metadata, thus revealing his exact location. Roberts took the photo down. But mistakes kept happening.

“It really blows my mind how some people choose to vend on here without knowing, well, shit,” Silk Road user HEATfan wrote.

It was impossible for anyone to protect all Silk Roaders from themselves.

Photos via Ross Ulbricht/Facebook (remix by Gwern)

In early 2013, Silk Road staff and top vendors began “receiving emails from law enforcement offering financial incentives and immunity to prosecution to use our positions of trust to completely hammer the Silk Road defenses of vendors and if possible, Dread Pirate Roberts,” an anonymous vendor told the Daily Dot.

The attacks seem to have taken a toll on Roberts. Most vendors passed forwarded him the police emails. But one vendor told the Daily Dot that Roberts seemed legitimately concerned that someone would eventually turn.

Only a short time prior, Roberts had acquired a reputation for dropping long missives about libertarian revolution. In 2013, those letters slowed drastically. One anonymous vendor said that Roberts’s demeanor changed drastically early in the year.

In January 2013, the FBI claims that Roberts paid $80,000 for the torture and murder of a vendor he believed was stealing from Silk Road. The man paid for the hit turned out to be a U.S. federal agent. The torture and murder was staged.

In March 2013, another federal charge alleges Dread Pirate Roberts was confronted by a Silk Road user named FriendlyChemist, who boasted of owning a long list of real names and addresses of Silk Road vendors. Unless Silk Road paid him $500,000, FriendlyChemist said he’d publish those names. Roberts apparently agreed to pay $150,000—but not to his blackmailer. Instead, he hired a hitman anonymously over the Deep Web, tasking him the murder of FriendlyChemist, whom he believed resided in Canada. No murders in Canada during the time period match the descriptions of the hit.

The murder charges are glaring contradictions against the high-minded ideals that both Ross Ulbricht and Dread Pirate Roberts have publicly professed.

On May 24, a Silk Road user sent Roberts a private message warning that an external IP address had been “leaking” from Silk Road during another round of maintenance.

The FBI believes this address was a virtual private network (VPN) server, a secure network through which Roberts could remotely log into Silk Road from his own computer. One way to understand the technology is to imagine a VPN being a “private tunnel” between two computers, which allowed Roberts to access the Silk Road server without anyone knowing he was behind it.

The leaked IP address resolved to a server company in the United Kingdom, an anonymous source with knowledge of the situation told the Daily Dot. That source believes that Roberts soon changed companies as a result of the leak.

The FBI criminal complaint lists a number of Silk Road-related IPs, one of which implicates dataclub.biz, a server-hosting company, as the host for Silk Road’s forums. The hosting for Silk Road’s marketplace was separate. The locations are still unconfirmed.

Although Roberts deactivated the code that leaked the IP and changed the way he accessed Silk Road, the information still eventually reached the FBI. No one outside of the FBI is quite sure how at this point. Silk Road’s hosting company was later subpoenaed by the FBI, who found the server contents wiped except for information on the last login from Laguna Street in San Francisco, right down the block from Ross Ulbricht’s residence.

By July, Roberts was clearly intent on spending money on protecting himself and defending the Silk Road from law enforcement and hostile attacks. The FBI alleges that Ulbricht ordered nine fake IDs as part of an effort to build up a stock of servers to bolster Silk Road’s security. The IDs, which Ulbricht ordered on Silk Road, were intercepted at the Canadian-American border on July 10.

On July 23, Homeland Security visited Ulbricht’s San Francisco home and questioned him about the fake documents. For whatever reason, he told the agents that “hypothetically” anyone can buy IDs off of Silk Road on Tor.

Shortly before police visited Ulbricht’s home, Dread Pirate Roberts agreed to his first on-the-record interview with a journalist. Forbes’ Andy Greenberg had sought the interview for eight months before finally landing it. The scoop, Roberts told Greenberg, was that Silk Road had been sold. He wasn’t the original owner of the black market.

Roberts granted the interview to Forbes on July 4, just weeks before the FBI came knocking on his door. Even at the time, many Silk Roaders immediately disbelieved Roberts’ new claim, saying that it was just as y likely that there was a single person behind Roberts ashalf a dozen.

On the day the interview made headlines around the tech world, Roberts publicly declared the war on drugs over, “and the guys with the bongs have won.”

Freedom Hosting, an anonymous Web-hosting company and perhaps the most important and popular Deep Web service in existence outside of Silk Road, was busted Aug. 3. Few details have emerged about how law enforcement found and took down Freedom Hosting. Its fall shook the entire anonymous Web. Roberts felt compelled to address his website and confirm that he still had control of Silk Road.

Aside from the largest trove of child pornography on the Internet, Freedom Hosting’s most interesting client was TorMail, the anonymous email of choice for Silk Road users. The FBI came into possession of the TorMail servers and all its data when they busted Freedom Hosting. Although Roberts has said he never used TorMail, almost all of his closest advisors and biggest sellers did, many of whom did not take basic precautions such as encrypting messages.

Every unencrypted message became property of American and Irish law enforcement, who are believed to have shared the information with other agencies around the world.

In addition to the pressure from law enforcement and the two murders that Roberts is charged with ordering, Silk Road faced a press from competitors. The rival black market Atlantis had a well-built website, produced TV-worthy commercials, and made several big waves across media. A series of July upgrades on Silk Road were widely seen as a response to Atlantis. Black Market Reloaded remained a formidable rival and the foremost weapons market on the Deep Web.

In addition to the pressure from law enforcement and the two murders that Roberts is charged with ordering, Silk Road faced a press from competitors. The rival black market Atlantis had a well-built website, produced TV-worthy commercials, and made several big waves across media. A series of July upgrades on Silk Road were widely seen as a response to Atlantis. Black Market Reloaded remained a formidable rival and the foremost weapons market on the Deep Web.

However, despite its apparent early successes, Atlantis suddenly closed on Sept. 20. Citing “security concerns outside of our control,” the market’s owners killed it for good.

Due to a long-held suspicion of Atlantis, the shutdown was met with gloating from some Silk Roaders. However, one question underpinned even the biggest gloat: If someone can get to Atlantis, is it possible that they can get to Silk Road?

Just days later, one of the oldest and most knowledgeable members of the Silk Road community announced that he was leaving. Kmfkewm, who once ran the Open Vendor Database, another online drug market, bid farewell to Silk Road for good on Sept. 29 for no discernable reason. He told fellow community members that his departure was nothing to worry about.

Three days later, on Oct. 2, Silk Road was seized by the FBI.

The criminal complaint alleges that 1,229,465 transactions were completed on the website from Feb. 6, 2011 to July 23, 2013, involving 146,946 unique buyer accounts and 3,877 unique vendor accounts. The total revenue generated was 9,519,664 bitcoins, equivalent to $1.2 billion in revenue. Silk Road collected 614,305 in commission, or $79.8 million—although those numbers are difficult to adjust for the fluctuating value of Bitcoin.

If these numbers are even close to true, Silk Road was many times bigger than any previous estimates.

Police found Ulbricht in the Glen Park branch of the San Francisco Public Library. He’d taken a seat in the sci-fi section with his laptop. Patrons reported a crashing sound around the building. FBI agents descended upon Ulbricht as soon as he opened his laptop and entered his passwords, seizing his machine and marching him out. The police confiscated approximately $3.6 million in bitcoins.

The end of Silk Road, along with the arrest of and allegations against Ulbricht, have inspired an outpouring of grief from Silk Roaders

“This is supposed to be some invisible black market bazaar. We made it visible,” an unnamed FBI spokesperson told Forbes. “[N]o one is beyond the reach of the FBI. We will find you.”

Despite that threat, the arrests of Silk Road vendors, and the end of the Deep Web’s most famous black market, the illegal commerce of the Deep Web marches on.

Other marketplaces, such as Black Market Reloaded and Sheep Marketplace, are already attempting to fill the enormous vacuum left by Roberts. Over a dozen major Silk Road vendors have expressed interest in building new black markets, hoping to make launch something even bigger.

Dread Pirate Roberts took a black market and forged it into a profound ideological statement—or was it just the new back-alley dope deal? Either way, Roberts launched a Silicon Valley success story, valued by the FBI at over $1 billion. No one should be surprised when an armada of new pirates emerges from over the horizon.

Illustration by Jason Reed