In 2017, the state of Georgia passed a domestic terrorism law in the wake of the Mother Emanuel AME church shooting in neighboring South Carolina, where nine Black people were murdered at a Bible study.

It was sold as a means to thwart future hate crimes, but was criticized by First Amendment advocates for being overly broad in its language. Many were concerned it would be used to squash legitimate political dissent.

After a slate of arrests in Atlanta over the past two months, critics may be right.

The bill said that any felony action meant to “intimidate the civilian population” or intended to “alter, change, or coerce” government policy can be classified as domestic terrorism.

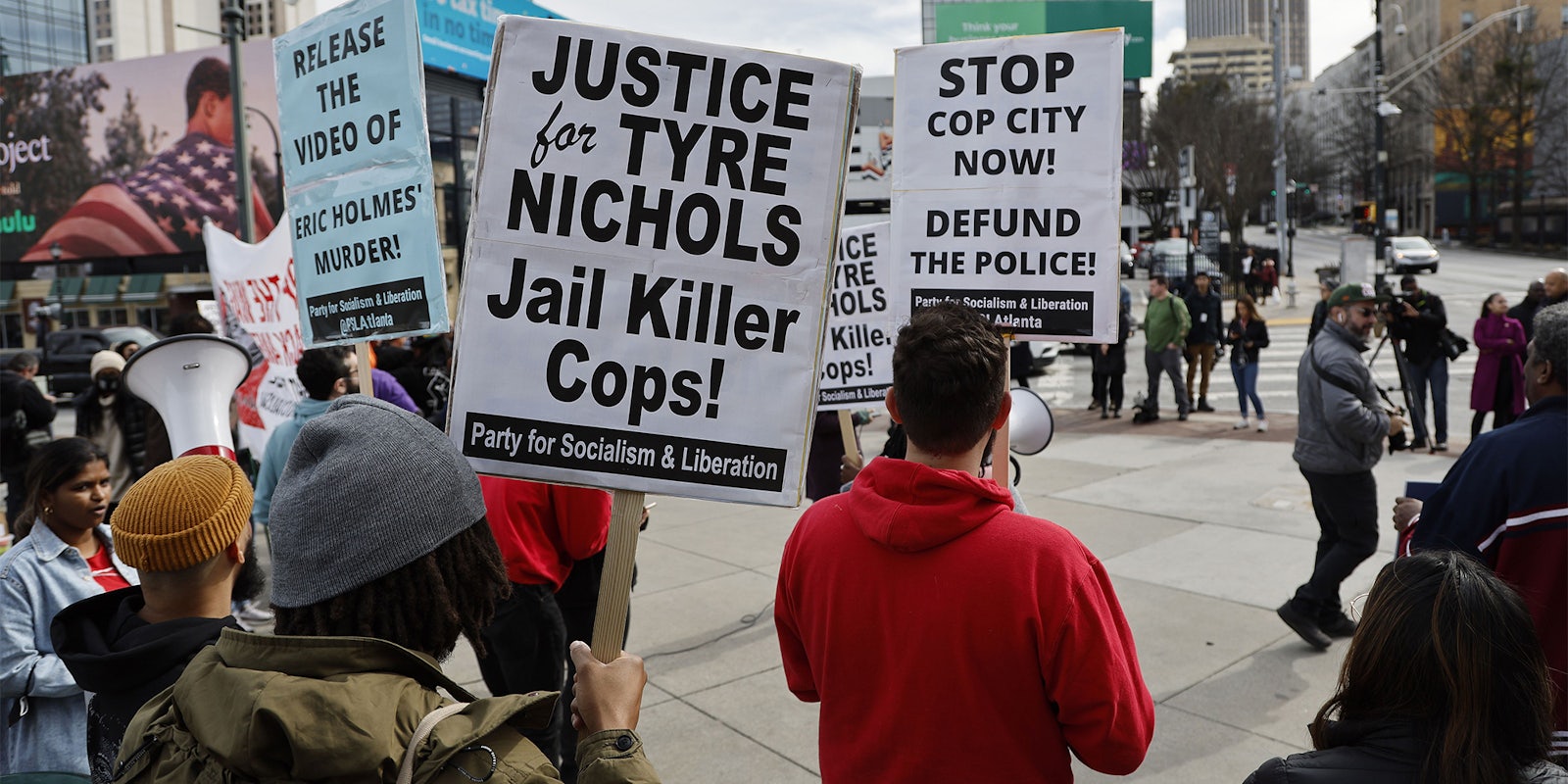

In the wake of the growing discontent surrounding an 85-acre police training facility in a forest outside Atlanta known as Cop City, 19 Defend the Forest Atlanta (DTFA) activists have been charged as domestic terrorists under the new state law.

Many legal experts are criticizing the charges as politically motivated overreach, and an attempt to squash legitimate, protected dissent.

Michael German, a former FBI agent and a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice, told the Daily Dot, “Terrorism is defined by its perceived political intentions, and as a result, including this term in a criminal charge is likely to lead to politicized applications. State and local law enforcement have a history of viewing themselves as protectors of the status quo power structures, and view protests against powerful institutions and interests as security threats. Giving law enforcement a broad statutory authority to determine who is a ‘terrorist’ can be expected to lead to abusive applications of that power.”

The arrests stem from two raids that occurred in the forest in December and January and a protest in downtown Atlanta on Jan. 21, 2023, in the wake of a Georgia State Trooper killing a forest occupant, Manuel Teran, during the January raid.

The warrants attempt to explicitly tie protest and dissent to the statute, noting of one January arrestee that he was with a group that “used explosive fireworks toward police in an attempt to coerce, intimate police policy, government policy,” building a case around the new law.

On the arrest warrants from the December raid claim, Georgia Bureau of Investigations agent Ryan Long claimed that the Defend the Forest Atlanta was “a group classified by the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) as Domestic Violent Extremists.”

DHS, however, denied that it specifically classifies any group with that term, saying that it does use the term to refer to any U.S. individual or group “who seeks to further social or political goals, wholly or in part, through unlawful acts of force or violence”

Long additionally listed a host of actions that the “group has publicly claimed responsibility for,” including throwing Molotov cocktails and committing arson, all designed to support his claim DTAF is domestic terrorism.

But none of the individual charges that are listed on the individual arrest warrants include any of these accusations.

One individual is charged with “being located on the property while wearing camouflage clothing and possessing incendiary devices.” It doesn’t specify what that device is.

Another is accused of “occupying a tree house while wearing a gas mask and camouflage clothing.”

Yet another is charged with “occupying a treehouse on the site, refusing to leave, and posting videos and calls for actions on social media sites used by DTAF.”

Besides three allegations of rock-throwing, the 14 forest defenders’ warrants do not accuse the defendants of committing any of the acts that could conceivably be construed as terrorism.

The warrants, though, dance around that, using associations with the group to justify the arrests for action police say it is guilty of.

“Said group has publicly claimed responsibility for numerous acts while stating their Intent was to intimidate employees of the government and private companies into not accepting or completing tasks in and around the site of the Atlanta Police Training Center. These acts have included vandalism at offices and private residences; throwing Molotov cocktails, rocks, and fireworks at uniformed police officers; arson of public buildings, heavy equipment, private buildings, and private vehicles; shooting metal ball bearings at contractors; discharging firearms at critical infrastructure; preventing access to private land and several other violations of law. These claims of responsibility have been made on websites, social media, and graffiti ‘tagging.’ The accused affirmed their cooperation with DTAF by occupying a tree house on the site, refusing to leave, and posting videos and calls for actions on social media sites used by DTAF.”

The plans for Cop City were devised behind closed doors with no public input by the Atlanta Police Foundation and City Council in September 2021, voting to approve the development despite residents expressing dissent.

The plan calls for a $90 million facility paid for in part by the city and police foundations, where cops will build a mock town to rehearse raids and practice police tactics. Critics of the proposal want to save acres of forests in Atlanta, one of the nation’s leafiest cities, from being turned into a training ground for police to learn better ways to arrest citizens.

Kamau Franklin, a Stop Cop City organizer, said that “the Atlanta PD, the Atlanta Police Foundation, the corporations, the developers—have all decided this is far more important than what the city residents want for themselves.”

And the cops behind it are doing their best to silence anyone against it.

Joshua Schiffer, an attorney representing two of the defendants, stated in a virtual bond hearing last December that “these are political prisoners that are protesting, using their First Amendment right to set forth what is clearly a popular opinion that this property should not be developed in the manner that local government has determined it should be.”

Status Coup interviewed one of the forest defenders who was arrested at the January raid in which Teran was killed and a Georgia State Trooper wounded.

The Georgia Bureau of Investigation claims Teran shot at officers first and was killed by return fire. The activists, however, disagree. Georgia Bureau of Investigations said there is no body cam footage of the shooting.

A forest defender described the events in detail, “I heard the gunshots early on, just a couple of minutes after I woke up. And I assumed there had been some people passing through the night before, that I didn’t know very well. And it seemed that people in the chats thought it might have been them … I had no knowledge of anyone in the forest even having a weapon. And certainly, no one had ever discussed with me any intent of violence. The entire point of this protest is that we are just sitting in a public space.”

Another Stop Cop City activist, Mathew Johnson, was more explicit, “It was a murder—we’re dealing with police that labeled protesters terrorists while they were sitting in trees minding their business.”

At the protest on Jan. 21, in response to the killing of Teran, the Atlanta Police Department tackled and arrested a protester who had been marching and carrying a banner. Witnesses say the department’s officers also randomly grabbed several others, throwing them on the ground and cuffing them.

It is not clear that these individuals were responsible for acts of vandalism that occurred at the protest, such as broken windows or a cop car being set on fire.

One arrested was Graham Evatt, who can be seen in a video marching with a banner at the front of the protest. According to his attorney, Steve Nicholas, “He was not involved in any vandalism. He does not know any of the other defendants in this case. He went out to hold a sign. Everybody ran and he didn’t. That’s why he got arrested.”

This has not stopped the Atlanta District Attorney from charging him, and others like him, as domestic terrorists. His arrest citation appears to use some of the same guilt-by-association logic as Long’s arrests.

It states that Evatt “engaged in activity that led to a large crowd who committed significant damage to windows and a police car.”

At Evatt’s bail hearing, the prosecutor claimed that he was a danger to the community and that because he is from Atlanta he may be one of the “primary organizers” of the protests again Cop City. “He is local, judge, and a lot of the other defendants are not, so we submit that there is a high likelihood that he will re-offend as far as participating in other events like this.”

He was given bail of $355,000 and released after four days in prison. He remains under house arrest.

On Twitter, after the protest Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens agreed with the police’s assessment that DTFA wasn’t engaged in peaceful protest.

“These individuals meant violence and used the cover of peaceful protest to conceal their motives,” he wrote.

And during Gov. Brian Kemp’s (R) recent State of the State address, he praised police efforts, “Just this past weekend when out-of-state rioters tried to bring violence to the streets of our capital city, State Patrol, Sheriff’s Deputies, and the Atlanta Police quickly brought peace and order. That’s just the latest example of why here in Georgia, we’ll always back the blue.”

Even if it means branding citizens terrorists.

Correction: This post originally misidentified where Steve Nicholas works. He is an independent attorney.