One of the biggest consumer markets in the world resides in a river valley about 200 miles southwest of Shanghai. You can find almost anything you want in Commodity City’s half-million stalls: baby bibs, knitting supplies, sundry types of underwear, T-shirts, glitzy jewelry.

The market is the literal and figurative heart of Yiwu, a metropolis of 1.3 million people that bustles under the sticky, industrial haze of Zhejiang province. Journalist Tim Phillips has called Yiwu the “Wall Street” of China’s counterfeit goods industry—an accurate, if somewhat narrow, label. The city’s factories flood the shelves of Commodity City and the rest of the world with a lot more than just knock-off iPhones and pirated Hollywood DVDs. They relentlessly pump out the type of cheap consumer goods you’re used to seeing at shopping mall kiosks and street-side trinket stands.

It’s in part because of factory cities like Yiwu that Etsy, an online marketplace that specializes in handcrafted goods, has become so successful. Since launching in 2005, Etsy has ridden an Internet-powered counter-industrial revolution, adding a personal and DIY touch to goods—everything from sweaters to Christmas ornaments. Craftsmakers have fled to Etsy to escape the price-cutting effects of big-box stores and their walls of factory-made products.The crafts marketplace has formed an alternate commercial universe with 30 million members and nearly 1 million stores, all ostensibly running on human labor and handmade goods.

It goes without saying that If Yiwu-type products began infiltrating Etsy, they’d upend the market—the same way Walmart destroyed your local department store or Barnes & Noble ended the era of the corner book shop.

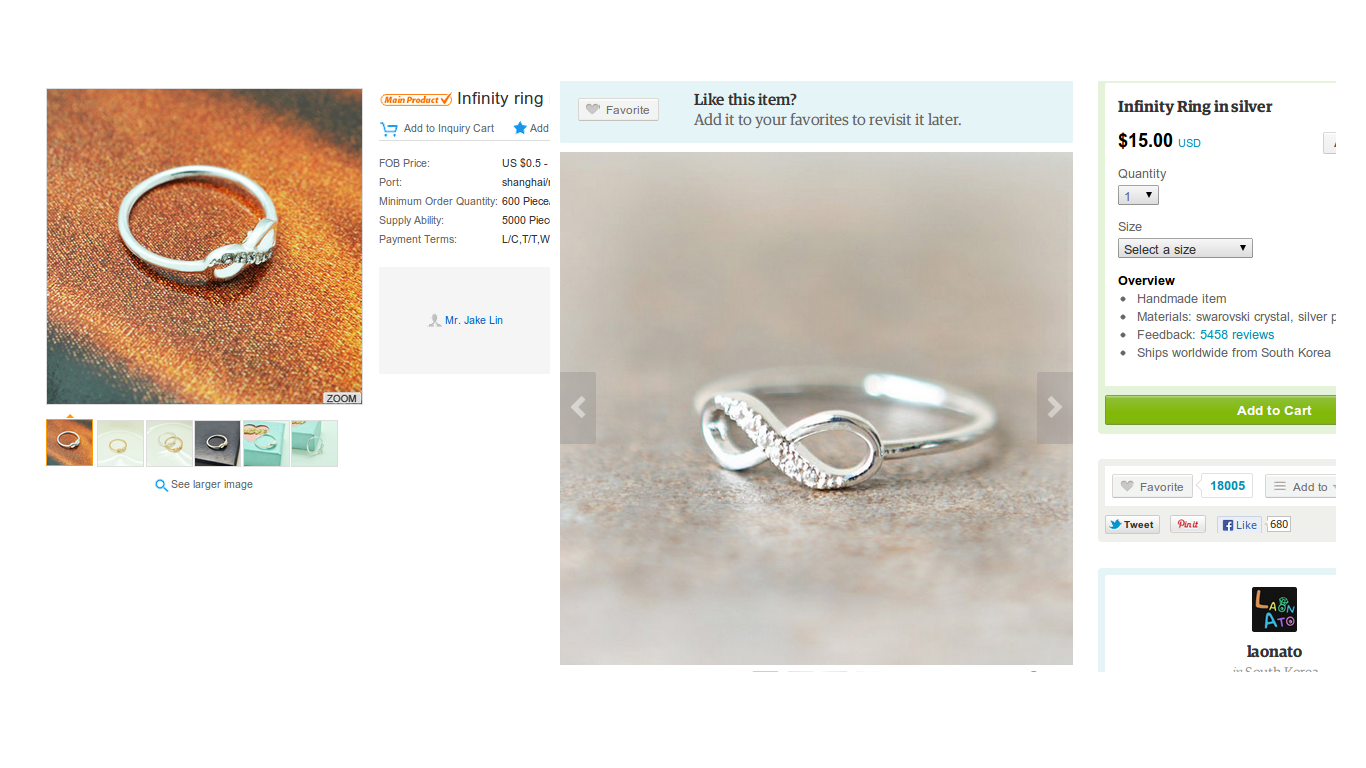

Take a look at the “Infinity Ring,” a delicate brass loop coated with a silver sheen and topped with rhinestones and crystal. In pictures of the factory where it’s made, you can see rows of workers in surgical masks bent over dusty tables, not far from bulky industrial machines. From ports in Ningbo and Shanghai, the Yiwu Daihe Jewelry Corp. exports the ring to anywhere in the world at 50 cents a piece.

You can buy it on Etsy’s most popular jewelry store for $15.

How? To most Etsy users, the obvious answer is that Laonato, the store, is buying the rings wholesale from the factory, then pawning them off as handmade goods, reaping a monstrous 2,900 percent profit. That practice is known as “reselling,” and it’s a subject of intense controversy on the site. But like with a lot of things on Etsy—where the entire economy operates behind the shroud of the Internet—easily drawn assumptions and reality rarely align as neatly as you’d expect.

As its leaders struggle to redefine the company’s corporate identity, the blurry, ungraspable truth about the Infinity Ring hints of a chronic ailment at Etsy’s core—one that could undermine the company’s ambitious plans and the marketplace as a whole.

Robot charm

In 2010, Chad Dickerson, Etsy’s chief technology officer, made a list of things he liked on the site, something just about every Etsy user has done at some point. He called it “Welcoming our new robot overlords,” and it was a curated selection of some of his favorite robot-themed tchotchkes. Something Dickerson failed to notice, like a lot of other unsuspecting Etsy users over the years, was that one of his chosen items was actually factory-born.

The “robot charm necklace,” as it was called, had no business being on Etsy, much less the CTO’s hand-picked list of favorites. And it was a testament to the company’s spotty record policing mass-produced merchandise that it would stay there for two years without anyone noticing.

Indeed, many critics, including the now defunct site Regretsy, have suggested Etsy lets resellers slide because it makes the same 3.5 percent cut off every sale, whether the goods are handmade or not. Etsy store owners have become so furious over this entrenched reseller problem they launched watchdog blogs and forum groups on Etsy itself, where members have for years carefully recorded and reported every instance of a mass-produced good they can find. Regretsy even featured a regular segment called “not remotely handmade.”

That’s not to say Etsy doesn’t try to stop resellers. When users flag an item, the report heads to the site’s Marketplace Trust and Integrity Team, usually referred to as MITS, which is basically Etsy’s customs department. An algorithm called SCRAM (Systems for Catching Resellers and Abusers of the Marketplace) also sniffs out some of the more obvious signs of reselling.

When a store receives enough reports from either users or SCRAM, the team will usually begin an investigation. For store owners it’s a somewhat laborious procedure. They’re compelled to detail their process with step-by-step photos and long questionnaires, all to prove their goods really do abide by Etsy’s rules. But as thorough as it may seem, SCRAM’s investigations can still backfire. That’s what happened in February when husband and wife duo Ming and Ingrid got booted from the site, despite painstakingly chronicling their process—not once but twice.

‘A mass-produced tchotchke shop’

Etsy has always been about more than just a collection of online storefronts. In 2008, the company’s “About” page spoke in grandiose terms of building “a new economy” that would reconnect “buyers with sellers” who would “buy, sell, and live handmade.” This wasn’t just some soulless ecommerce site—it was a lifestyle. Etsy soon became the engine of a burgeoning online handcrafting movement, a proof of concept that a separate universe of handmade goods could not just exist but flourish.

But there were cracks built into the foundation—resellers being an obvious and intractable example. There was also limit to just get how big crafters could grow before they needed to leave, meaning that users might start their business on Etsy, but they had to move elsewhere to really grow their business.

In May 2012, Wired’s Rob Walker captured Etsy’s existential crisis with a profile of Terri Johnson, an Etsy businesswoman who complained of becoming a “one-woman sweatshop” incapable of growing or taking a break as she struggled to fulfill the orders pouring in. In the real world, she might have just taken on some investment, bought a small factory, and hired a staff to churn out the orders. But Etsy’s rules stipulated that everything needed to be handmade; outsourcing your labor to others wasn’t allowed, nor was using industrial machines.

By 2011, many of Etsy’s most successful stores were considering jumping ship.

Rather than opening the Etsy umbrella wider by fiddling with the rules, the site’s cofounder and then-CEO Robert Kalin doubled-down, refusing to budge on the handmade ethos.

So the board kicked him out.

In July 2011, the company promoted Dickerson to CEO, and he immediately went about rewriting what Etsy was about. Some of Dickerson’s changes were small, focusing on functional benefits to a broad swath of the community, like implementing a payment system for mobile devices. Others targeted sellers like Thompson, including a change that Wired’s Walker characterized a “startling departure” for the company: allowing sellers to self-identify as “designers” and outsource production. Store owners could now have a third party assemble part of a product, even by machine, so long as that contribution didn’t amount to a “majority share” of the final product. Here’s Etsy’s rule on the subject:

“A third-party vendor may be used for intermediary tasks in some crafts. Acceptable examples include, but are not limited to: printing the seller’s original artwork, metal casting from the seller’s original mold, or kiln firing the seller’s handcrafted ceramic work.”

As Dickerson and other leaders went about reinventing Etsy, users began digging through his history. That’s when Regretsy’s April Winchell discovered Dickerson’s “robot charm necklace,” still sitting there two years after he’d favorited it.

“I love the irony of welcoming our new overlords,” one user wrote at the time, referring back to the title of Dickerson’s list. “Why not just make etsy a mass-produced tchotchke shop and call it a day. there’s got to be a better way.”

The discovery of the factory-made necklace was like a gallon of gasoline tossed into a brush fire. There had already been a groundswell of outrage in April 2012, after Etsy’s official blog posted a glowing profile of Ecoligica Malibu, a California store that sold furniture made from reclaimed wood. Etsians alleged the furniture was actually assembled in a Bali factory, imported to California, and resold as handmade goods. They had solid evidence, too, including the fact that Ecilogica Malibu shared an address with a wholesale retailer in California.

Etsy, ignoring those specific complaints, explained that Ecilogica Malibu, despite hiring a small team of workers, was operating entirely with the rules. It was a “collective,” a vague term that basically allows entire shops to run, so long as each crafter assembles a different part of the final product.

According to Etsy’s rules, that might look like this:

One artist screen prints fabric, then another artist sews clothing from the fabric. The finished product is listed in a collective Etsy shop.

With Dickerson’s changes, however, a store can also now outsource its designs to a machine cutter, which makes a larger collective sound more and more like an assembly line, with each “member” simply being one step in the assembly process.

In May, 3,500 stores—or about 1 percent of Etsy’s total marketplace—closed shop entirely for a day to protest what they saw as the company’s anemic response to the reseller problem. It was an unprecedented moment in Etsy’s history. A few months later, Ecologica Malibu mysteriously disappeared from Etsy.

The company responded to the strike by buffing up its MITS team with more staffers. But the reseller problem hasn’t gone anywhere. Just last month, Etsy users complained that the site featured a factory-made item in a promotional email. And the comments section to a recent blog post from Dickerson was littered with complaints about resellers.

“Please, please be honest with your Etsy community and let us know where resellers stand in the future of Etsy,” one shop owner wrote. “It is wonderful we are 30 million strong, but if a large portion of those millions are resellers then we are not gaining but losing.”

Handmade wholesale

Then there’s the Infinity Ring, one of just many products you can find on Laonato that appears to originate from Yiwu. Laonato, which is based out of South Korea, dominates jewelry sales on Etsy, according to independent analytics site Craftcount.

Take the “owl and moon necklace,” for instance, which is made by the “Yiwu Colorstone Commerce Firm” and sells on China wholesale site Alibaba for $1 to $2.50 apiece (a minimum order of 600 is required). Laonato sells it for $20. At $29, the store’s “leaf ring” is a pretty good deal, too. The Yiwu Xiloo Jewelry Firm can ship 20,000 of the exact same ring for 50 cents each. The leaf ring, the owl and moon necklace, and the Infinity Ring are all sold on other Etsy stores, meaning someone, somewhere, is probably selling a factory-made good.

I found the above items in about five minutes, after copy-and-pasting names from Laonato listings into the Alibaba search engine. It’s certainly suspicious. So why haven’t they been banned?

Since Etsy was ignoring my emails, I reached out to Laonato directly. The store’s owner politely explained I had everything backwards. They weren’t pawning Chinese manufactured goods as real merchandise.

Chinese manufacturers, the rep said, were stealing their designs and photographs.

“This is our biggest concern recently,” she wrote. “Of course, we buy and use some pendants, charms and beads from the suppliers. but these items are made by myself and my staffs.” That staff amounts to the owner, her two sisters, and a packer, she told me.

Etsy’s MITS team, the rep continued, had already reached out and asked for photographs of their production process, just the same as they did with Ming and Ingrid. In Laonato’scase, the MITS team was satisfied with the shop’s evidence.

Laonato sent the same photographs to me but asked that we not publish them. In one, you can see tools and materials laid out on a work bench. In others, you can see a worker pulling wiring taught, a plastic mold for a ring, and an image of the computer design file for the ring. All in all, there was nothing that implied the photographs couldn’t have been taken in China, and nothing to imply they weren’t taken in South Korea.

For its part, Yiwu Daihe Jewelry Factory denies the allegation it’s stealing photographs and designs.

“There’s no need to steal other’s design, we have our own designer who can develop kinds of jewelry,” spokesman Mango Du wrote. “The photos of the infinity ring in our website were taken in kind,” she continued, attaching two photographs that showed piles of the rings on what looks like a black velvet tabletop.

You can start to see the conundrum Etsy finds itself in. How can it accurately inspect the manufacturing processes of a million shops from all over the world, especially when the company’s changed focus to such a broad and vague extent that the word “handmade” no longer even appears in its mission statement? The only way to really prove a thing would be to undertake on-site inspections, and that would be prohibitively expensive.

If Laonato’s allegations are true—if it really is the victim—the store is still benefiting mightily from Etsy’s rule changes. If everything their rep told me is true, then the company is still no one-person shop. It’s a four-person assembly-line of skilled workers, churning out jewelry that’s pre-cut by machines at a fraction of the expense of a single worker laboring by hand. Laonato even offers orders in “wholesale,” a word that, a few years ago, would have been hard to imagine ever being legitimately associated with an Etsy store.

Counterfeit futures

Laonato’s story might seem hard to believe, but there are actually a lot of Etsy stores getting ripped off by Chinese manufacturers—a second front in what seems like an uncoordinated war on the site’s hobbyists and single-person shops.

Trish Hadden’s bags are definitely handmade. The 53-year-old flight attendant from Albuquerque, N.M., sews her personalized label into each one, which she sells for anywhere between $12 for smaller purses to $60 for a handbag.

But like with Laonato’s jewelry, you can find Hadden’s bags on Alibaba—the commerce site that connects Chinese manufacturers to wholesale purchasers around the world and claims to be as big as Amazon and eBay confined—where they’re offered by the Hangzhou Dawnjoint Business and Trading Company for $3 to $4 apiece. The company, based out of the capital city of Zhejiang province, didn’t respond to a Daily Dot request for comment. It’s been plundering more than Hadden’s designs. The firm has stolen her photographs—which included images of her hand-sewn, personalized tag—and superimposed their own store’s logo on top.

The photos of Hadden’s bag (left) were copied by Hangzhou Dawnjoint Business and Trading Company and posted directly to Alibaba (right).

Other Chinese manufacturers are doing the same thing. By last week, Hadden told me that nearly every other product on Allibaba’s “chevron tote” bag listing, for instance, was a design stolen from Etsy users, which she backed up with links to the items on both Etsy and Alibaba. Four of those Etsy store owners confirmed to me that they never gave Alibaba suppliers permission to copy their items.

Alibaba’s leadership has actually taken a fierce anti-piracy stance in recent months. Founder and chairman Jack Ma has called counterfeits a “cancer we have to deal with.” A group of Alibaba brass are set to visit the U.S. later this month, where they’ll have earnest discussions with corporate and government interests in three American cities about intellectual property issues.

This sudden PR campaign comes, not coincidentally, a few months before the company’s much-anticipated initial public offering. Alibaba wants to calm investors who are rightfully skittish over its toothless track record combating counterfeit goods.

Like Etsy, Alibaba did not respond to a request for comment on this article. But a representative did post a message to the Etsy forums, where Hadden has been marshaling users to complain about the problem. The rep assured the forum that Alibaba was taking their claims very seriously—that it was moving quickly to rein in counterfeiting, including “partnering with five key government and law enforcement agencies in China to tackle piracy problems… head on.”

“We are happy to report that, working in close collaboration with the Etsy community, we are making great progress in cracking down on merchants on Alibaba who violate the intellectual property rights of Etsy artisans.”

Living up to its word, Alibaba has since since removed many of the counterfeit goods Hadden discovered. But one shop I spoke to, TriggerDesigns, has already seen their bags reappear on another Alibaba storefront and have, in turn, already filed another complaint.

That’s the future of copyright enforcement on Alibaba: If Etsy store owners want to protect their designs, they’ll have to drop the sewing needles, plop down in front of their computer, and scour Alibaba for a few hours every day. Because no one will do it for them.

Commodity City

I was first tipped to all the resold and counterfeit items on Etsy by Joan Fritsch, 52, who lives in suburban Chicago. She’s been planning to open up a jewelry shop on Etsy for a while, but says she can’t compete with the rock-bottom prices from stores like Laonato.

“I’m not sure I want to sell on Etsy because of all the things I see on there. It just undercuts the whole community.”

Hadden is losing enthusiasm too. She’s been sewing since the age of 11 and would love to leave her stewardess gig behind. But trying to get her Etsy store off the ground is “a struggle,” she said—not just because Chinese manufacturers are stealing her designs, but because of resellers.

“There’s is a ton of competition on Etsy. I’ve noticed it’s being flooded with resold stuff. People are buying bags and slapping monogram on it and calling it handmade. It’s not handmade if it’s a leather bag and it’s $15.”

This catch-22 is a sadly predictable result of Etsy’s rule changes: The company wants to cash in on the success of its most popular storefronts, so it’s changed the rules to keep them on site. That’s created a highly competitive market for hobbyists or small-time crafters, scaring some away.

One has to wonder if former-CEO Kalin’s unwillingness to compromise on Etsy’s principles might have been a strategic decision, and not a product of naive idealism. Sure, Etsy lost money when it failed to accommodate growing businesses. But it also kept its hundreds of thousands of other storefronts happy in the knowledge that no one backed by a production line was going to price them out of business.

There are still hundreds of thousands of store owners loyal to Etsy, or at least dependent on it. But now, Etsy’s protective shell is looking more and more fragile. Lone craftspeople are being squeezed on three fronts: the proliferation of mini factories that fit uneasily into Etsy’s vague new rules, the Chinese manufacturers stealing user designs, and Etsy storefronts brimming with factory-made goods.

How long until browsing Etsy isn’t much different than taking a stroll in Commodity City?

The brave new economy is starting to look a lot like the old one.

Illustration by Jason Reed