Looking back on a decade of internet scamming, trying to find the most representative or prophetic events, is exhausting. It’s impossible to get an accurate headcount. In the wake of a big scam, there are countless others of varying size and intention. But the bigger takeaway is the normalcy: Scamming is just another thing we do online now.

Still, for a generation raised on phones and screens—and the idea that you can have multiple identities—scamming became part of the culture. If you can stand out, you can build a fanbase. The “lifestyle” scammer, at least as it exists online, is a byproduct of the internet’s aspirational drive to make something, with “influencer” taking on a new meaning.

That extends to established scams, too. The Nigerian prince email scam has been circulating almost as long as email has existed. My spam filter is still consistently full of emails starting with “Dear” and asking for help with complicated financial transactions—and, most importantly, trust. Amazingly, the scam has only flourished over the decade as a new generation of “Yahoo boys,” named after the email service, has stepped up. Writing for ZAM in 2018, Olivia Ndubuisi detailed the office spaces that house Yahoo boys and the different skill sets needed to pull off hustles, which include bank fraud, romance scams, and business scams.

Yahoo boys are young and often have college degrees, but few job prospects. Further, a culture has developed around what they do. There are songs about the glamorous life of a Yahoo boy and the money they bring in. It’s aspirational for a lot of young people. Earlier this year, U.K.-based Nigerian rapper Naira Marley released “Am I a Yahoo Boy” in response to Nigerian singer Simi denouncing the glorification of fraudsters in Nigerian culture. Soon after, Marley was arrested for online fraud.

In the States, a series of big scams—the 2008 housing crisis, student debt, lack of affordable healthcare—fed into smaller scams of the 2010s, assisted by a critical shift in technology. While Rule 34 typically applies to porn, it can also be applied here. If an app exists, there’s been a scam on it: Venmo, Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Netflix, TikTok, Spotify, YouTube. Vice’s Allie Conti recently detailed an elaborate fake-host scam run through Airbnb, which forced the company to change its policies. Cash App has evolved the advance-fee scam, as Benjamin Powers wrote in a recent piece about #CashAppFriday: “Scammers are preying on the financially desperate with updated Nigerian-prince tactics. Moreover, the company doesn’t seem to be doing anything about these scams and provides fertile territory for them under one thirsty hashtag.”

In 2010, Facebook hadn’t yet become a global menace; The Social Network came out in October of that year and was a critical success—the visionary nerd (Jesse Eisenberg, giving Mark Zuckerberg a personality) versus the establishment. In 2019, Zuckerberg is an unblinking billionaire living in a bubble. In Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion, Jia Tolentino devotes a chapter to the generational effect of scamming, and says of Facebook: “Even if Zuckerberg didn’t set out to consciously scam the people who signed up for Facebook, everyone who signed up—all two and a quarter billion monthly users (and counting)—has been had nonetheless. It’s our attention being sold to advertisers. It’s our personal data being sold to market research firms, our loose political animus being purchased by special interest groups.”

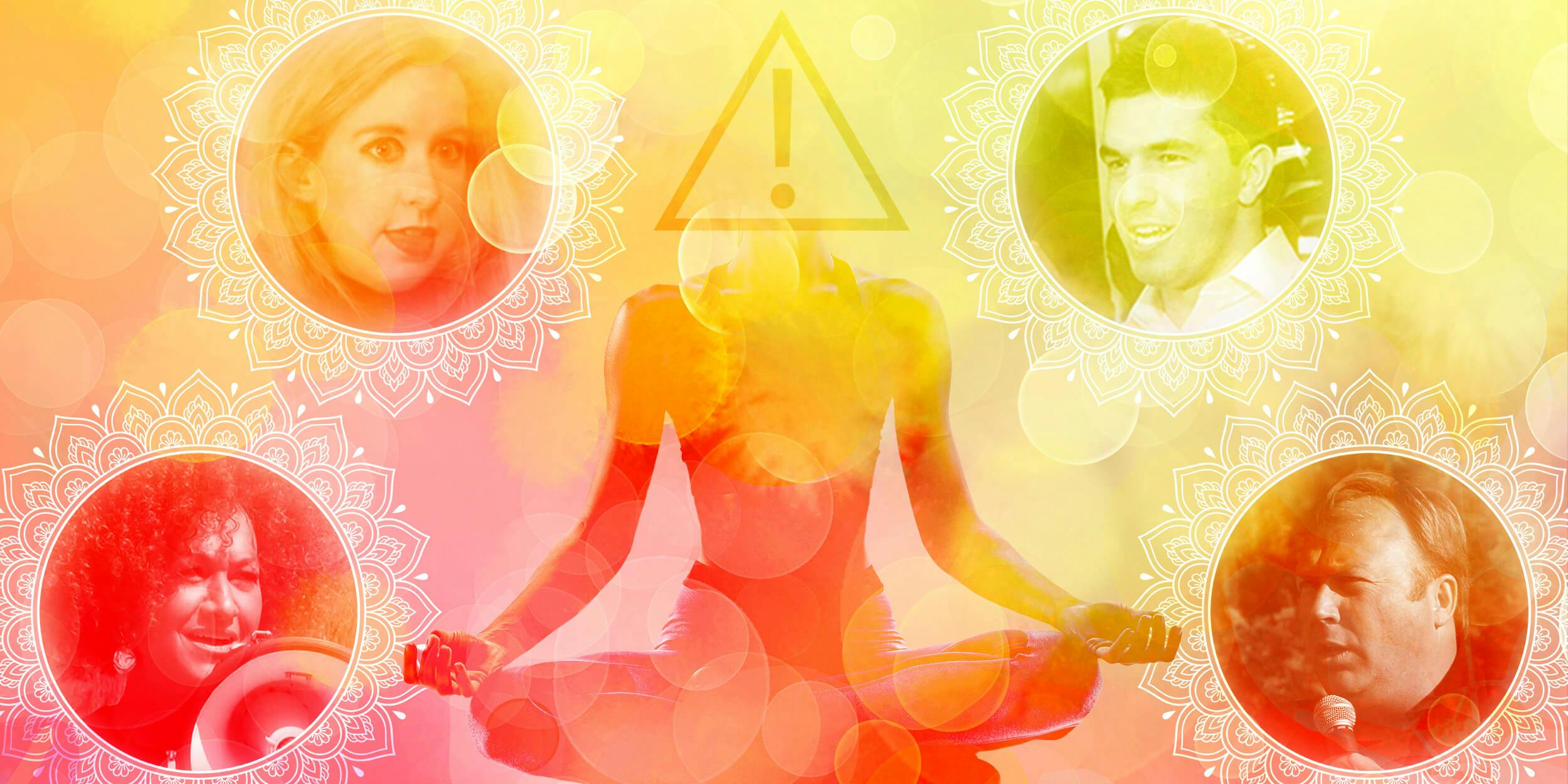

The last few years have seen more personality-centric scams. Caroline Calloway was called out in early 2019, after her Instagram-promoted “creativity workshops” were revealed to be expensive, empty gestures. Though she apologized, over the summer Calloway cheekily christened her post-backlash creativity workshop “the Scam” and fans seemed ready to give her another chance (and more money)—one Instagram commenter asked whether people who attended were expecting to be scammed. In September, a woman named Natalie Beach revealed that she had been ghostwriting Calloway’s posts, which opened up the question of how many other people do this kind of job.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B5OtWOGBdC9/

“Energy alchemist” Audrey Kitching made a name for herself by selling a marked-up vision of spirituality and healing, and was accused in early 2019 of being a thief, fraud, and abusive boss. Kitching rose to fame as a Myspace personality, but in the midst of the Instagram wellness boom, she was able to transfer her talent for getting noticed into a new aesthetic. Anna Sorokin, aka Anna Delvey, is now in prison for her scams, but the scope of her ruse is truly astounding. Sorokin fashioned herself as a German heiress, spending extravagant amounts of cash all over New York City and documenting her travels on Instagram before her arrest in 2017. In this case, the scam had a payoff: Her story is being made into a Netflix series from Shonda Rimes, though she might not get to profit off it.

The ultimate lifestyle scam of the decade might be Fyre Fest, a long, dumb con that targeted millennials with money to burn; left thousands stranded in the Bahamas; and produced dueling, ethically questionable documentaries. Its now-jailed architect, Billy McFarland, already had several failed business ventures in his pocket, but people still put their trust in the exclusive island experience he offered, promoted through sexy and mysterious Instagram posts. The spectacular failure made his on-camera quip in Netflix’s Fyre Fest doc—“We’re selling a pipe dream to your average loser”—even more delectable. Adding another level of fuckery, FuckJerry, the meme account tied to the media company that produced the Netflix doc, ran its own scam for years, lifting jokes and memes from Twitter and Instagram without consent and using them for ads.

While we’re actively awaiting the next Fyre Fest, there’s something empty about our fascination with these personalities. In a New York Times article about millennial scammers, Amanda Hess assesses: “The closest-held secret of modern scam artists is how woefully unimaginative they really are. Our oversaturated scam culture seems to have produced something new: utterly unappealing con men and women who could not credibly be referred to as ‘artists’ at all.” And yet there are now countermeasures like Baller Busters, an Instagram account that exposes the alleged luxe lifestyles of young entrepreneurs and influencers who claim they can help others get what they have. The term Milkshake Duck has evolved to cover so many personalities who go viral for something positive, until something inevitably makes us turn heel.

Earlier 2010s stunts offered a glimpse of what was coming: Horse_ebooks, a Twitter spambot that drew in a massive following with its mangled bursts of prose, often tweeted links to ebooks and was rumored to be run by a Russian developer. In 2013, author Susan Orlean curiously revealed it was really an art installation from two New York City creatives (one of them a BuzzFeed employee) who took over the account in 2011. It traded in manipulating perception rather than money, but there was still a sense of betrayal. We thought we knew this random Twitter account. The story of Notre Dame player Manti Te’o’s elaborate catfishing captured the internet’s imagination in 2013 and added a weird new chapter to the romance scam. It was parodied on SNL and Funny or Die, but showed that emotions can be manipulated as easily as bank accounts. The Federal Trade Commission claims that in 2018, victims of romance scams were swindled out of $143 million. In 2015, it was $33 million.

Not only that, but whether you believe it (or want to believe it) the car salesmen will continue to laugh

— Horse ebooks (@Horse_ebooks) September 16, 2013

The 2009 Balloon Boy incident didn’t happen online but Twitter became the platform for reacting to it. In a tenth anniversary piece for Mel, Miles Klee draws a line from the hoax to our current anything-goes media landscape and pinpoints an element we’d see in scams to come: “Really, the flight of Balloon Boy was an accidental, overwhelming success on the wrong terms, demonstrating how far and fast America would run with nothing much at all.”

The 2016 election introduced a whole new line of grifters. Trump entered office as a scammer and his hangers-on gleefully followed suit, using his name and influence to con people. As conspiracy theories went more mainstream over the last few years—many of them recognized by the president—scamming took a dangerous turn. Infowars host Alex Jones has been able to make money off ludicrous claims, like that Sandy Hook was a hoax; he’s hawked dubious supplements on his website that promote “male vitality,” and water filtration systems that, ostensibly, filter out the stuff that’s making frogs gay. Anti-vaxxers have found insidious new ways to push their beliefs on the vulnerable and Amazon happily hosts books that promote fraudulent science. The last few years have also seen the rise of the #Resistance grifter, online personalities who espouse anti-Trump rhetoric but have found a way to profit off it.

Entertainment has shifted, too. As fandoms grew in online communities like Tumblr and Twitter, so did interest in exploiting their devoted fanbases. Country singer Kip Moore told the New York Times that women have left their husbands to be with him after corresponding with impersonators and fake accounts. Oprah stood in front of a Christmas tree in December 2017 and issued a “fraud alert!” to followers; someone was impersonating her online. In the summer of 2018 (aka the “summer of scam”), the Hollywood Reporter detailed the exploits of the “Con Queen of Hollywood,” who impersonated executives like Amy Pascal and Kathleen Kennedy and targeted industry people with trips to Indonesia under the guise of work, only to drain the marks of money over the course of the trip.

Joanne the Scammer, a character brought to life by Branden Miller, parodies white-woman confidence and privilege and became a hit in 2016 with the mantra, “I’m a messy bitch who lives for drama.” (Ironically, that same year Miller was scammed by someone who took over his Twitter account and demanded ransom.) Miller recently brought Joanne to the premiere of Netflix’s The Politician, a series about scammers, but he tells the Daily Dot that the tide has turned since 2016 and it was difficult to evolve the character.

“It’s kinda like the Santa Claus thing,” Miller says. “Once they find out it’s fake the hype was over. I’ve generated fans from it and that’s cool, but I don’t think people are into fake scammers.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U-t0-65dHrw

After a long stretch of movies about con men, the last few years have seen more interesting real-life stories about women, like Can You Ever Forgive Me? and Hustlers. One of the year’s best films, Parasite, is outwardly about a poor Korean family scamming a wealthy one, but it also shows the emotional toll that “fake it till you make it” can have on the perpetually struggling.

Documentaries have proven more difficult: HBO’s The Inventor, about Elizabeth Holmes—the Theranos CEO who pushed a bogus blood-testing technology and managed to secure funding from the likes of Henry Kissinger and Jim Mattis, before being charged with fraud in 2018—showed how easily a con can grow in Silicon Valley, but didn’t offer much insight into who Holmes is. (Jennifer Lawrence is set to play her in an upcoming film, however.) Netflix’s documentary about Rachel Dolezal—a former NAACP leader who resigned in 2015 after her parents revealed she’s actually white, and was later charged with welfare fraud—showed the limitations of trying to humanize or analyze scammers, as did Netflix and Hulu’s Fyre Fest documentaries.

Lie, Cheat & Steal, a podcast hosted by comedians Kath Barbadoro and Pat Sirois, grew out of a shared fascination with “liars and hustlers” and well as the Elizabeth Holmes story. Though they cover a range of hucksters, from art prankster Joey Skaggs to hoax metal band Threatin, Barbadoro says “it’s been interesting to see the themes of what we talk about repeated over and over again in different fields and on different scales.”

Those themes also invite introspection: “We end every episode with the question of whether or not the scam was ‘worth it,’” says Sirois, “and I think that’s a soft way of asking ourselves, ‘Would you do it?’ And if you’re being totally honest with yourself there’s gonna be times when the answer is yes. So I think it’s that level of relatability that makes someone gravitate to [a] good scam story.”

As scammers have evolved their strategies, our instincts for sniffing out bullshit also evolved. But there’s been a shift in the definition of scamming. Is it a scam to engage in “dogfishing,” in which people on dating apps use photos of dogs that aren’t theirs? Or is that just a hack to get noticed?

“We’ve become way more hip to spotting fake accounts and sensing that someone is a bot simply by how they type,” says Sirois, “but it seems we’ve become less resistant to a Caroline Calloway type using her platform to scam us into buying tickets to her nonexistent creativity workshop.”

“Yeah, there’s a lot of grey area in online ‘scamming’ now,” Barbadoro adds. “Obviously there are the outright crimes, but is it a scam to, for example, Facetune your photos, or to sell your followers on a fictitious and more fabulous version of yourself in exchange for a monetizable platform? If we’re all trying to fake it till we make it, how much faking is acceptable before the whole thing becomes a fraud?”

That’s the encompassing question, one that has evolved from a decade where creating a version of ourselves and making it monetizable has allowed for autonomy and also elevated the language of swindling. But the scam is still essentially about trust. It might take another decade before we really see what the internet has done to ours.