From the moment humans created technology that could share messages with a large audience, we used it to seek out mates. Frances Beauman, author of Shapely Ankle Preferr’d, dates the first personal ad back to as early as 1695, centuries before the invention of smartphones, just shortly after the invention of the printing press.

Over the few hundred years that followed, personal ads went from novelty to commonplace. It’s no surprise that video dating took hold in the VHS heyday of the ’80s, or that when the internet entered our homes in the ’90s, we dove into chatrooms seeking sex and companionship. Soon a whole new world of internet dating emerged. But in the 2010s, smartphones came along and dating apps came nipping at their heels. Suddenly, online dating was always within reach. Our pockets buzzed with new matches, and our thumbs ached from swiping. By the end of 2014, Tinder boasted an estimated 50 million users a month. And by 2015, cultural pundits declared that the Tinder apocalypse was upon us. Before we knew it, the world of online dating was on fire.

You could argue that swiping destroyed dating as we once knew it. But you could also say that over the past decade, dating apps put our modern dating rituals through a sort of trial by fire. Technology ramped up the speed and volume of our connections, and suddenly the pitfalls and frustrations of modern dating were impossible to ignore. The very same technology that led to dating burnout proved itself capable of rapidly evolving and responding to our needs and preferences. By the time the Me Too movement sparked a massive online dialogue about consent in late 2017, the apps and their users appeared to be listening.

As the decade began, we dipped our toes into the possibility that online dating might be more “normal” than not. In 2010, Catfish was released. The documentary was so popular that MTV later launched an entire series dedicated to bringing people who fell in love online together IRL only to reveal that the objects of their affection were rarely who they promised to be.

The original film followed would-be series host Nev Schulman as he pursued a real-life meeting with a woman whom he’d met and fallen for over Facebook. The trailer was famously misleading, suggesting horror and thrills when, in reality, the film’s conclusion was melancholy. Schulman discovers the woman he fell for is actually an unhappy housewife who maintained several fake accounts and whose initial foray into online deception was an attempt to share her paintings as if created by a child in order to avoid facing harsh criticism.

Catfish is the perfect representative of how we related to online dating at the beginning of the decade. Even the New York Times’ A.O. Scott gave it reluctant praise, writing, “The dark genius of [Catfish] lies… beyond the parameters of its slick intentions, in the wild social ether where nobody knows who anybody is.”

People regarded online dating with some suspicion and apprehension. And, yet, stories about how online dating might go “wrong” were often more sad than terrifying.

Catfish was a moment of demystification. By telling a story that showed the very human appeal of meeting someone through the internet, Schulman and filmmakers Ariel Schulman (his brother) and Henry Joost humanized online dating and all the disappointments it might entail. And viewers were hungry for more. The wildly popular television series that followed is going into its eighth season. Catfish may owe a great deal of its popularity to its promise of lurid details and shocking deceptions, but it points to our growing fascination with finding romance online.

And then along came Tinder. While gay dating apps like Grindr and Scruff had already pioneered the use of geolocation services by showing its users who was nearest in 2009 and 2010, Tinder changed the online dating game—by making dating into a literal game.

In a 2017 live chat, Tinder co-founder Jonathan Badeen explained: “From the beginning, I had a nagging desire to gamify it.” Initially, Tinder was designed to allow users to flip through a digital stack of cards and then sort those matches into piles. But Badeen felt using buttons to sort the cards was clunky and slowed down the process. Wiping a foggy mirror clean with a wave of his hand as he emerged from the shower one morning, he was struck with inspiration, and swiping was born.

From its earliest days, Tinder drew criticism for its seemingly superficial approach to dating. Photos became the centerpiece of the matching experience, and bios became brief and superfluous. Reading one required an extra flick of the thumb, and for users eager to rack up matches, the incentive to read about a potential match before saying “yes” or “no” became negligible.

Previous online dating platforms like Match and OkCupid had relied heavily on user-supplied information, but Tinder offered its users the opportunity to select their own matches via a pared-down, speedy experience. Swiping left or right on a face may have seemed shallow to critics, but you could argue that Tinder became so popular because it offered a more intuitive approach to matching—even if it did rely on baser instincts.

Joe Prisco, 36, a teacher based in New York City recalls that in the early days of Tinder, his friends were thrilled. “[My] pals [were like], ‘This is too good to be true, we can swipe on this thing all day and possibly get laid.’ [I thought], ‘This is creepy… but hey might as well give it a shot!’”

Christina Spencer, 35, a yoga instructor based in Portland, Maine, who then lived in Brooklyn, New York, recalls her roommate showing her the app and instantly hating it. “I was turned off by it from the beginning because it just seemed like a lot of pressure. Someone might be close by, you might ‘match’ and then there was this immediate option to meet up. And for most people meeting up meant hooking up.”

By 2013, Tinder was readily available on all smartphones running Android or iOS, and its use spread like wildfire. The app was racking up 350 million swipes per day (4,000 per second) by late 2013 and 1 billion swipes per day at the end of 2014, just two years after its launch.

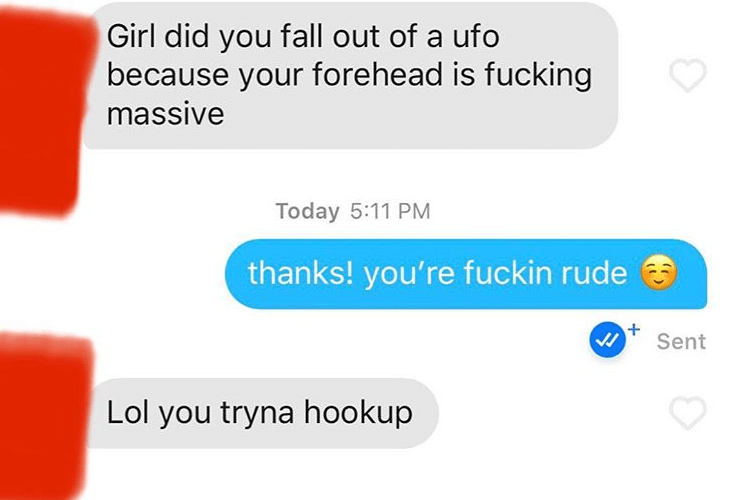

The world was fluent in the language of swiping. But the exchanges weren’t always pleasant. Late 2014 gave birth to the Tinder Nightmares Instagram account, which humorously documents some of the worst user experiences.

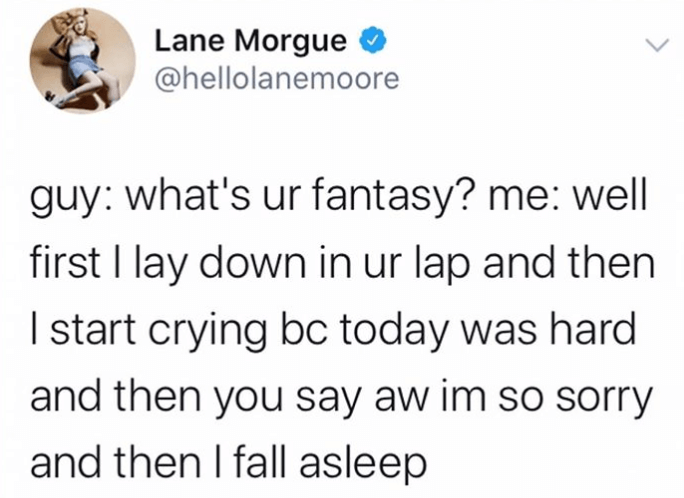

Also in 2014, comedian and writer Lane Moore launched their comedic show “Tinder Live,” which still runs at the Bell House in Brooklyn to this day. Moore, who is also the author of How to Be Alone, infused their show with humor about the chaos of online dating.

Tinder wasn’t just normalized; it had become a memeable spectacle. In this way, the “game” aspect of Tinder endured. It seems even when the app failed its users, it succeeded as a form of entertainment.

While many found relief in laughing at the more grim aspects of the app, in reality, Tinder was racking up some very real public relations nightmares. Tinder co-founder Whitney Wolfe filed a very public sexual harassment suit against her co-founders in 2014, and co-founder Sean Rad was booted from his position as Tinder CEO before the end of the year. By December 2014, Wolfe had launched her own swipe-based dating app: Bumble.

Wolfe’s victory settlement against Tinder and the launch of Bumble may have been just as pivotal in the evolution of online dating as swiping. Wolfe decided with her new platform, she would place more power in women’s hands. The app was designed so that only female users could initiate conversations with their matches. And if they chose not to, their matches would disappear after 24 hours. This allowed female users to be more selective in their interactions while giving them the incentive to take risks and engage.

By late 2015, Business Insider had dubbed Bumble the “best dating app,” citing better conversations and more real-life dates. But Bumble didn’t eliminate harassment, nor did it escape criticism. Some were skeptical of the app’s “feminist” branding and questioned whether forcing women to make the first move actually empowered women or just made them do more work. The app also had strict guidelines for its photos, and some users were frustrated when their images were removed for showing even a sliver of underwear.

But Bumble’s launch and its success reinforced swiping as the new normal. Even veteran online dating companies like OkCupid began adding swipe functionality. With a plethora of apps at our fingertips by the mid-decade, online dating had reached a crescendo. Everyone seemed to be online, and no one seemed to be meeting in bars anymore. As Nancy Jo Sales at Vanity Affair pointed out, if you visited a busy bar in New York City, you’d most likely find the patrons swiping on their phones. Sales claimed we were facing a “Tinder Apocalypse,” writing “Hookup culture, which has been percolating for about a hundred years, has collided with dating apps, which have acted like a wayward meteor on the now dinosaur-like rituals of courtship.”

READ MORE:

- What a hoax about Mitski being a ‘child predator’ taught us this year

- 2019 is the year the world turned on big tech

- Angela Brown, viral Popeyes chicken sandwich mastermind, is our Internet Person of the Year

Sales’ article went viral, and it became the centerpiece of conversations about online dating. But her diagnosis may have been a bit dramatic. In 2016, the Atlantic’s Julie Beck suggested that perhaps we were facing a case of dating-app fatigue. The novelty of apps had worn off, and its users were tired and unimpressed with the results of their efforts to find love and connection. Beck deduced, “If there’s a fundamental problem with dating apps, one baked into their very nature, it is this: They facilitate our culture’s worst impulses for efficiency in the arena where we most need to resist those impulses.” While Beck and Sales reached different conclusions about the severity with which dating had been impacted by the apps, their articles shared an underlying theme of increased harassment and crossed boundaries. Women, in particular, seemed to be dismayed by the apps, not necessarily because they weren’t finding love but because they were exhausted from fending off so much harassment.

Sensing the fatigue, the companies facilitating online dating again made shifts. Hinge, a dating app founded right on the heels of Tinder in 2012—but to far less fanfare—originally included swiping functionality, but unlike Tinder, it linked users based on their Facebook connections. After reading Sales’ Vanity Fair piece, Hinge founder Justin MacLeod decided the app needed a redesign.

The Hinge redesign was released, along with a really bizarre animated video.

The new Hinge offered a handful of potential matches per day, promising quality over quantity. In lieu of swiping, its profile interface required users to scroll through a profile of images interwoven with responses to prompts. You could dismiss a profile, or, if you liked what you saw, “like” an element of the profile and send a message about it to the desired match.

Jon Hess, 27, is a Los Angeles-based writer and comedian who frequently uses multiple dating apps but says he prefers the user experience on Hinge. Hess told the Daily Dot, “Since I’ve downloaded [Hinge] the conversations that I’ve started to feel a little more natural.” Hess added, “Prompts instead of bios give us less creative license, in a positive way…[I also like that] the answers are dispersed between your photos so people see it.”

Hinge continued its rebranding strategy to much success. In 2018, Hinge became the first app to measure its users’ real-world success with the “We Met” feature, prompting users to share how their dates went so that Hinge could better identify their type for future matches. In 2018, the app was also acquired by Match group, and in a 2018 Q3 earnings call, Match said that Hinge downloads had increased five times since Match had invested.

While Match chose to double down on the “hook up” reputation of Tinder by marketing it as an app for singles, it leaned into the opposite approach with Hinge: A 2019 campaign dubbed it “the dating app designed to be deleted.” Also in 2019, presidential hopeful Mayor Pete Buttigieg shared that he met his husband on Hinge, and the app’s downloads tripled, with a 30% increase in the number of gay men on the app.

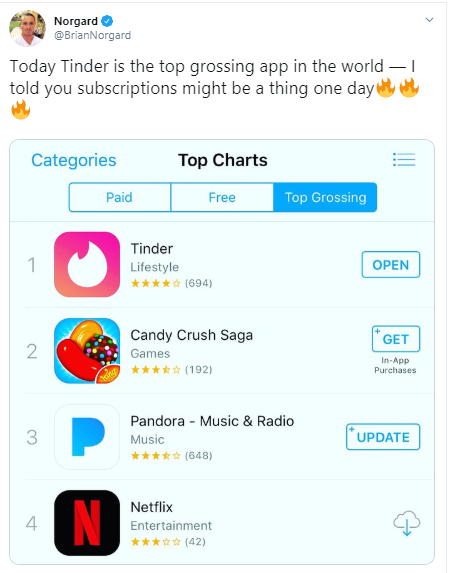

Meanwhile, despite its poor reputation, Tinder’s business continued to boom all decade long. According to Forbes, in 2017 the app was valued at $3 billion. In August of 2017, Tinder released Tinder Gold, a premium subscription option it had tested in international markets; in the U.S. Tinder became the top-grossing app, beating out Candy Crush and Netflix for the No. 1 spot in the app store. In early 2019, Cheddar reported that Tinder’s valuation had leaped to a staggering $10 billion, making it clear that while the app may be publicly reviled its revenue has yet to bear the consequences.

Little more than a month after Tinder Gold hit the U.S., the Me Too movement went viral. Following news of the horrific allegations against Harvey Weinstein, actress Alyssa Milano tweeted words of solidarity and encouragement, asking women who’d been sexually harassed or assaulted to retweet and share their stories or to simply respond with “me too.” While the phrase had actually been coined a decade earlier by activist Tarana Burke, Milano’s platform catapulted the long-running conversation about harassment, assault, and consent into the mainstream. On Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, women shared personal stories of assault and harassment.

With Me Too, the undercurrent of harassment, consent, and safety issues that had plagued online dating and IRL encounters was at the surface. A 2018 study by the Pew Research Center found that following the date of Milano’s tweet, the #MeToo hashtag had been used roughly 19 million times on Twitter, with spikes in use at the time of related news events.

Since Me Too’s moment, the New York Times, NBC News, CBS News, the Huffington Post, and other major news outlets have reported on changes in dating behavior, online and off. Some reports are anecdotal, while many others cite an annual study by Match, the online dating company that now owns majority stakes in Tinder, Hinge, and a slew of other apps. According to Match’s 2019 findings:

“In our study, half of men (51%) say the #MeToo movement has caused them to act differently overall; more specifically, nearly 40% of men reported now being more reserved towards women colleagues at work and 34% of men said they act more reserved on a date because of the movement. In terms of age effects, this was especially true among Millennial men. Whether being more cautious and reserved is enough to reduce sexual harassment experienced by others remains an open question for additional research and observation.

When asked about #MeToo and various aspects of social life, both men and women reported being more reserved when approaching someone new in public (35%), as well as when on a date (33%), and also with what they post on social media (28%). When with a new potential partner, 19% of singles think twice about the jokes they make, 15% further consider the topics they discuss, and 15% are more cautious about inviting that person to come home with them.”

Despite Match’s findings, some say Me Too has given way to retaliation.

Lane Moore, who still hosts “Tinder Live” regularly in Brooklyn, told the Daily Dot they’ve noticed a disturbing pattern of increased anger from cis men on dating apps since Me Too. Said Moore, “So many dating app profiles I see [now] of men are really angry lists of what they hate about women on dating apps. It’s a real bummer because every gender is frustrated by modern dating for sure, but the number of men whose profiles read like, ‘Why I already hate you,’ is not a good look.”

Cara Kovacs, a sex and dating coach, has also observed problematic patterns in her clients following Me Too. “Paranoia is distancing men further from their ability to be authentic,” Kovacs explained. She added, “We need to be educating people about how to authentically and safely express their fears and desires. People get into online dating and they have absolutely no idea how to communicate with each other. Men don’t know how to communicate their fears and it comes out as rage.”

Julia Faye Blum, a bartender based in Brooklyn, is a veteran online dater. She told the Daily Dot that she senses the effects of Me Too on online dating have been somewhat insidious, with single men often posturing as more “woke” than they actually are in order to maintain access to women. Blum explained, “I feel like there are a lot of dudes out there who will say what women want to hear. They want to be that feminist guy and intellectually they think they are, but they aren’t doing that deep dive work to unlearn the patriarchal bullshit they’ve learned.”

Blum also reflected on multiple experiences where men who presented as feminist via their Tinder bios became aggressive and dismissive of boundaries once a date became physically intimate. When Blum reported one man’s behavior to Tinder, she was dissatisfied with the app’s response. “Looking back at it, he had definitely been trying to get me drunk. It felt like something he might do regularly. And their response was like, ‘There’s nothing we can do about it,’” she said.

Blum’s frustrations aren’t purely anecdotal. Tinder came under fire again in late 2019 when a report by ProPublica and Columbia Journalism Investigations found that one-third of women were sexually assaulted by someone they met on an app.

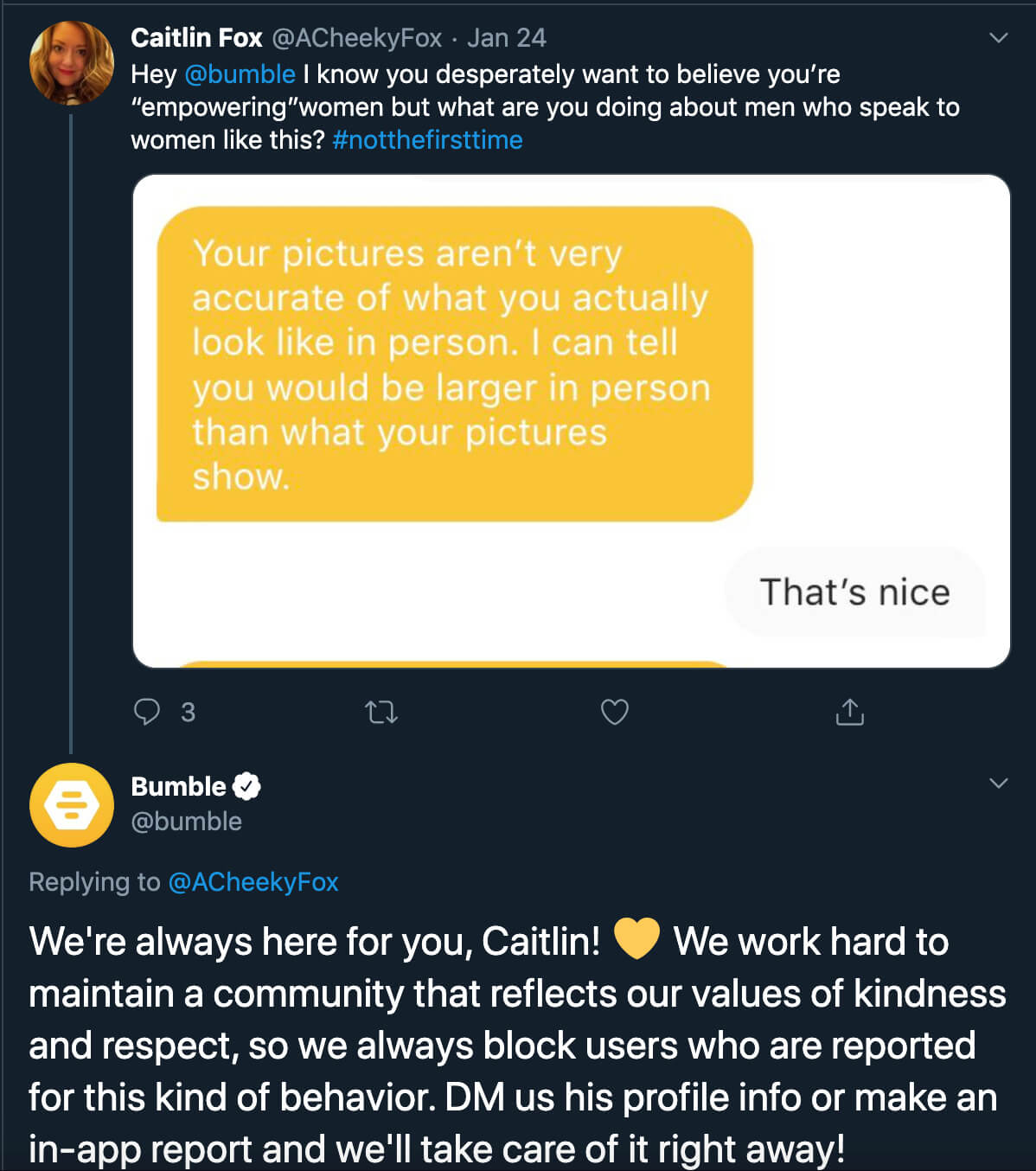

On the other hand, Bumble users routinely report that their complaints are met with respect. In the app and on Twitter, Bumble stands out for its responsiveness to user complaints.

Cecily Gold Moore, Bumble’s director of community experience, told the Daily Dot that standing up for mistreated users and blocking and banning those who don’t respect community guidelines is a priority for Bumble. The Bumble team has documented examples of poor behavior with personalized responses explaining why users have been blocked, with open letters like #DearConnor, #DearMichael, and #DearDylan.

Gold Moore said the company is also working to improve user experiences via technical updates: “[We] recently launched Private Detector, a new feature that automatically detects and blurs inappropriate images on our app, after we learned that one in three women have received an unsolicited nude image online.”

Offline, Bumble has also been working to support legislation to protect users from receiving unsolicited nudes. According to Gold Moore, Bumble recently supported a law in Texas which makes unsolicited nudes a misdemeanor. In other words, sharing dick pics without consent isn’t just frowned upon, it’s against the law. Since September 2019, sending an explicit photo without consent is punishable by a fine of up to $500. Bumble is now working with California Senator Ling Ling Chang to bring the same law to California.

“I feel like there are a lot of dudes out there who will say what women want to hear. They want to be that feminist guy and intellectually they think they are, but they aren’t doing that deep dive work to unlearn the patriarchal bullshit they’ve learned.”

As dating apps became big business, the social era’s transparency at least created higher expectations for how businesses conduct themselves. In the same way that consumers increasingly gravitate toward eco-friendly advertising, people interested in dating apps seek out options that align with their values.

As Gold Moore put it: “The most important thing we can do is listen to our users.”

There are, however, alternative apps that are doing things differently. One of the most celebrated apps that came out in 2019 is queer dating app Lex. Dating profiles on Lex are unlike anything else you’ll find in the world of online dating today. There are no pictures, just brief text-based personal ads in black and white, or sometimes set against a bright teal backdrop. Users can link their Instagram accounts to their profiles so you can browse their photos, but it’s not a requirement.

Formerly an Instagram account called simply, “Personals,” the idea for Lex was born when Kelly Rakowski, creator of the h_e_r_s_t_o_r_y Instagram account, invited her followers to submit personal ads to @herstorypersonals. Rakowski had been inspired by the bold, sexy personal ads in On Our Backs, an ’80s lesbian erotica magazine. While the Personals account has come under fire in the past for issues of white privilege, the back-to-basics nature of what Rakowski created has been wildly successful. The personals account posted over 7,000 ads before launching the Lex app in late 2019 in order to accommodate growing demands. While a few thousand ads may seem small compared to the overwhelming number of swipes on Tinder, the success of Personals and Lex points to a growing interest in doing things differently. If the Tinder apocalypse burned everything down, Lex could be the humble, bare-necessity tools innovative queers have gathered to build something new.

If there’s one takeaway from the last decade in online dating, it’s that the high-speed, high-traffic world of apps brought the problem areas of modern dating into plain view for all to see. This has led to feelings of burnout, frustration, and even despair. But it has also created room for important dialogues about what isn’t working—and how we can do better.

READ MORE: