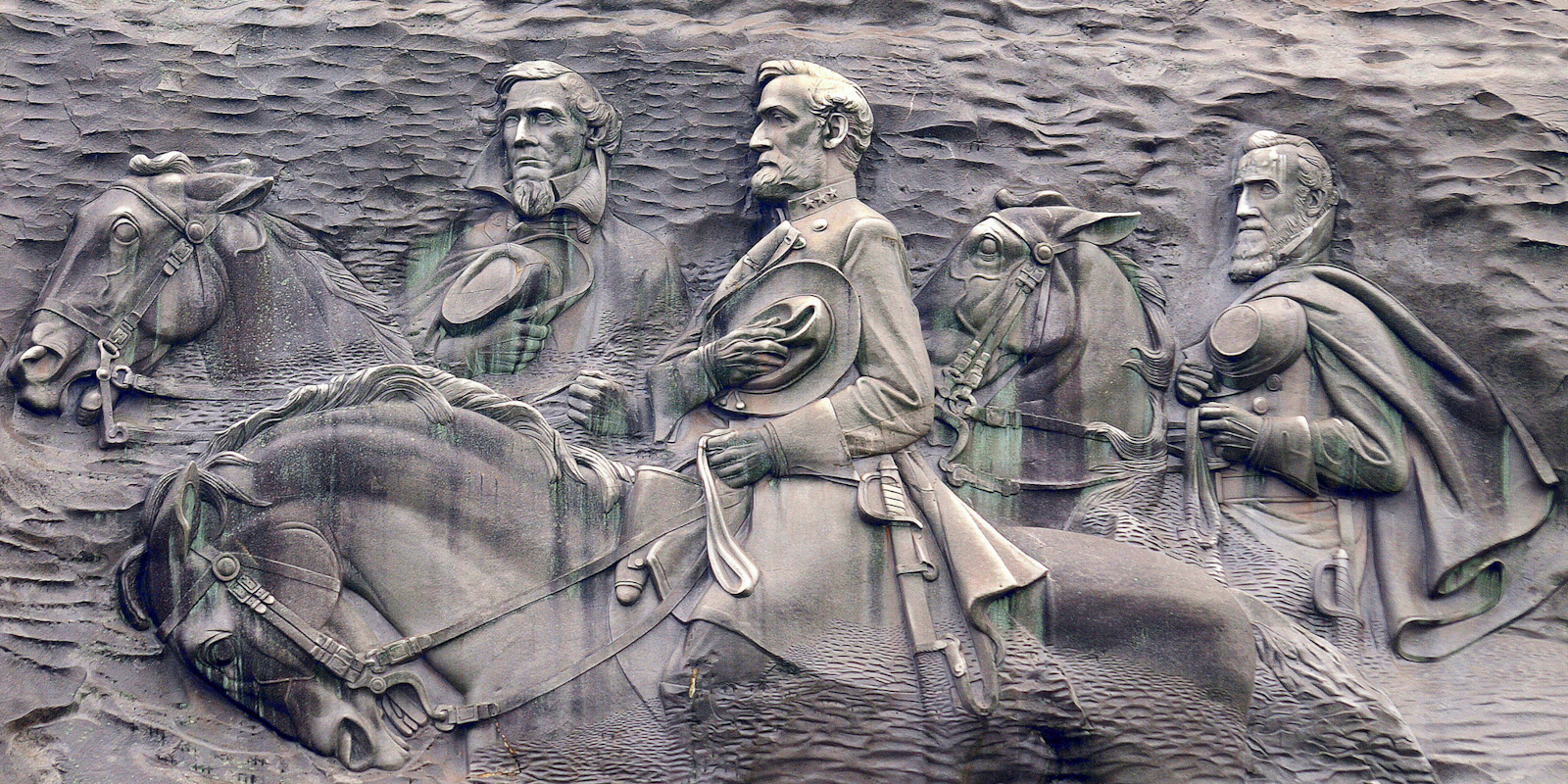

On Monday night, protesters in Durham County, North Carolina, toppled a Confederate monument before taking turns kicking the fallen statue. Last night, the city of Baltimore quietly took down all of its statues honoring the Confederacy. The mayor of Lexington, Kentucky also promised to “relocate” its moments. Cities across the country are taking measures to prevent a repeat of last weekend’s violent white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, which was ingnited in protest of the removal of a Robert E. Lee monument.

The removals of these Confederate images signal a change in how the United States commemorates—or wants to commemorate—the Civil War, particularly in how it symbolically justifies the actions of those who fought to keep slavery institutionalized in the South. Despite previous efforts to end the silent celebration of Confederate imagery, government officials made some of its most concerted efforts after Dylann Roof, a later-noted white supremacist who celebrated the Confederate flag, killed nine Black parishioners at a historic church in Charleston, South Carolina. Between Roof’s mass killing in June 2015 and this April, about 60 Confederate markers have been removed or relocated, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC).

Yesterday’s and last night’s efforts saw the removal of another five—but that’s only five in the hundreds of remaining Confederate memorials, flags, and namesakes in the country, as far-reaching as Massachusetts, California, and Washington. According to SPLC, as of April 2016 more than 1,500 Confederate symbols existed in public places—700 of them statues and monuments.

And despite fervent calls to retire Confederate flags and statues, protests like the one in Charlottesville send a clear message that the “heritage, not hate” is still a widely promoted excuse to justify the public existence of these monuments, with many white nationalists arguing that their removal is a way of “erasing” history.

However, this idea that the U.S.—and the South more specifically—should cling to Confederate imagery as a way to honor the nobility of “our” ancestors who fought the North is revisionism within itself. What those statues do is erase slavery and celebrate the men who believed “white” was the master race.

If you want to cite history, look no further than the founding documents and speeches of the Civil War, which promoted white supremacy and the idea that white people were superior to Black people. The Confederate flag was also soon appropriated by the Klu Klux Klan and segregationists after the war.

A report from SPLC also found that one of the most dramatic upticks in the erection of monuments and schools commemorating the Confederacy was during the first two decades of the 20th century. This spike coincided with the enactment of Jim Crow laws, which mandated that public schools, restrooms, transportation, restaurants, and drinking fountains be segregated between Blacks and whites. This was also around the time there was a resurgence of the KKK. More Confederate statues rose during the Civil Rights 30 years later. In other words, in times when white people felt threatened by Black equality, the erection of Confederate monuments was a way to remind the county that white people have always held power.

If we’re still talking about the idea of commemorating “history,” even Lee allegedly opposed the erection of Confederate monuments, and once wrote that doing so would “keep open the sores of war.” This, however, might have been more of a “revisionist” decision made in order to completely hide the South’s shameful defeat, biographer Jonathan Horn told PBS.

“Despite the well-documented history of the Civil War, legions of Southerners still cling to the myth of the Lost Cause as a noble endeavor fought to defend the region’s honor and its ability to govern itself in the face of Northern aggression,” SPLC reported. “This deeply rooted but false narrative is the result of many decades of revisionism in the lore and even textbooks of the South that sought to create a more acceptable version of the region’s past. The Confederate monuments and other symbols that dot the South are very much a part of that effort.”

Stephanie Meeks, president and CEO of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, acknowledged in a statement last month that many Confederate statues are in place to erase slavery and emancipation from our understanding of the war and reaffirm white supremacy.

“We cannot and should not erase our history,” she said. “But we also want our public monuments, on public land and supported by public funding, to uphold our public values…Whatever is decided, we hope that memorials that remain are appropriately and thoughtfully ‘re-contextualized’ to provide information about the war and its causes, and that changes are done in a way that engage with, rather than silence, the past—no matter how difficult it may be. We should always remember the past, but we do not necessarily need to revere it.”

If you’re wondering where all these Confederate symbols are in America, here is an interactive map from the Southern Poverty Law Center cataloging the 1,500-plus markers, museums, cemeteries, battlefields, and more: