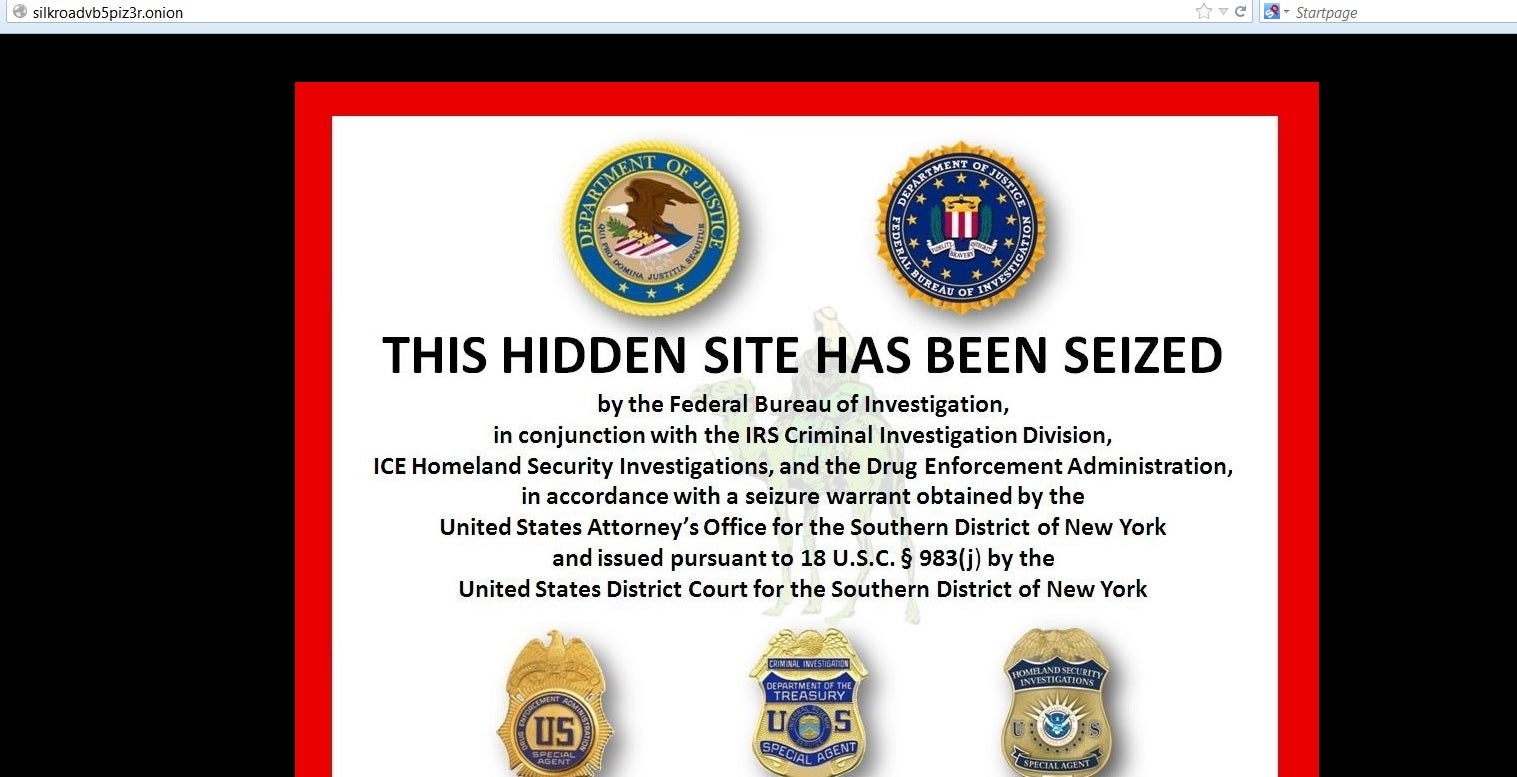

Silk Road wasn’t built in a day, but it dropped off the Internet in an instant.

On the morning of Oct. 2, 2013, the Federal Bureau of Investigation seized the infamous black market and arrested its alleged mastermind, Ross Ulbricht.

The fall of Silk Road shook the entire Deep Web—the unindexed, anonymous part of the Internet on which it was hosted—setting off a chain reaction of high-profile arrests and scams. Multiple new black markets opened and closed, stealing millions of dollars from customers and sellers alike.

Even before Silk Road’s closure, there was cause for serious concern. Freedom Hosting, the biggest host on the Deep Web and owned by a man the FBI called the “largest facilitator of child porn on the planet,” was taken down almost exactly two months prior. Days later, it was revealed that the National Security Agency was directly targeting Tor and its users.

From any number of angles, it appeared that a chink in the armor of Tor—the powerful anonymizing service that allowed these services to flourish—had been discovered and exploited. It seemed, for a time, like open season for federal authorities. The Deep Web was proclaimed dead.

“No one is beyond the reach of the FBI,” an agency spokesman triumphantly told Forbes. “We will find you.”

However, a comprehensive analysis of hundreds of police raids and arrests made involving Tor users in the last eight years reveals that the software’s biggest weakness is and always has been the same single thing: It’s you.

The plight of the exit node operator

At a basic level, Tor can be explained pretty simply. A user’s Internet traffic is passed through the Tor network where it is encrypted and bounced to three nodes—entry, middle, and exit—around the world. By design, only the exit node operator’s IP address ever shows up in public.

The exit node operators—there are about 1,000 around the globe today—bear much of the risk if illegal activity like child pornography passes through their particular node.

Why do exit node operators take it on? Tor has about 2 million connected users at any given moment, and while the drug busts make the headlines, the majority of Tor users actually utilize it to circumvent increasingly prevalent digital censorship and online surveillance.

When new exit nodes are set up, philanthropy and anti-censorship activism tend to be key motivators, especially around sweeping events like the Arab Spring.

“I became interested in Tor in the spring of 2007, after reading about the situation in Burma and felt that I would like to do something, anything, to help,” one Englishman, who later had his house raided due to his Tor exit node, explained.

After being developed as a U.S. Navy research project, Tor first launched publicly in 2002. By the middle of the decade, funding increased dramatically. So did police attention.

The first big raid came in 2006. Seven computing centers across Germany were raided on charges of proliferation of child pornography as part of a wider national investigation. The centers ran over half a dozen Tor exit nodes. Their hardware, the machines they use to do business, were confiscated by police.

The raid spurred frantic rumors that the country was cracking down on Tor. That wasn’t the case. The servers were returned after a few pounds of paperwork was finished.

“Child porn, not Tor, was the target,” Tor’s Shava Nerad explained at the time.

When most exit node operators get arrested, it’s because police have followed the trail to the IP address. Before he became Tor’s executive director, Andrew Lewman was once visited at home by Navy investigators for volunteering his hardware in the Tor network.

While most operators are eventually cleared of wrongdoing, the process still takes a toll. When another German exit node operators home was raided late at night the next year, the result was chilling.

“I can’t do this any more, my wife and I were scared to death,” one operator wrote after his home was raided in 2007. “I’m at the end of my civil courage.”

The year after that, U.K. cops swarmed the home of a Tor exit node operator and allegedly threatened him with child porn charges and to put his own children in protective services in the process. Months later, having cleared the man of wrongdoing, the police unceremoniously removed the man from the investigation.

In America, the story is different.

“Exit relay operators don’t see SWAT teams in America because detectives already know Tor,” Lewman said. “[Instead], they see two guys show up,” knock, and have a relatively informed discussion.

Lewman and Tor’s project leader Roger Dingledine have taken a proactive approach to educating law enforcement agencies, especially in the U.S., regularly speaking at places like the FBI Academy in Quantico, Va. Tor also developed a tool, ExoneraTor, that immediately tells a cop (or anyone else) whether an IP address of interest is actually a Tor exit node. It’s designed specifically to prevent needless raids against Tor exit node operators.

“It’s very hard to change a mindset if the first time you’re introduced to Tor is while tracking down a criminal. You may assume only criminals use Tor (you would be wrong),” Lewman explained in 2010. If we can talk to law enforcement first, they may look at Tor in a different light.”

That’s not to say problems haven’t occurred. A 2009 kidnapping case—where the suspect allegedly used Tor to brag and post pictures and video of what he said was a small boy being locked up—led to a full-on police raid on an exit node operator’s residence. The home of Nolan King, another exit node operator, was similarly raided in 2011 by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents.

Both Tor exit node operators were cleared of any wrongdoing—although ICE ominously warned Nolan that they might return in force anyway—but the raids were predicated by law enforcement’s profound misunderstanding or disregard of the way the Internet and Tor work.

An IP address—what’s potentially exposed by the exit node operator—is the number assigned to each Internet-connected device. However, an IP address is nothing like a fingerprint. It can be co-opted by hackers running bot nets or shared by many users if, for instance, a network is open at a cafe or library, or if a user is running something like a Tor exit node.

“This means an IP address is nothing more than a piece of information, a clue,” Marcia Hoffmann, who was a senior staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, wrote after the raid on King’s home in 2011. “An IP address alone is not probable cause that a person has committed a crime.”

Following a digital trail

One of the most impactful arrests of a Tor user occurred in November 2012.

William Weber, an Austrian exit node operator who worked as an IT administrator at a small Internet service provider, was grabbed early in the morning at his office and subject to a home raid. He ran a seven exit nodes for Tor at the time and said he handled up to 30 terabytes of data, which included the illegal child abuse media that set authorities in motion.

“I mainly run the exit nodes to make it possible for the not-so-privileged folks to have uncensored access to the internet, without fear of government prosecution,” Weber told the BBC following the raid. Police confiscated not only his computer but also his guns which he said he owned legally), consoles, electronics, and some drugs.

The Tor Project, which has historically offered some form of help to any exit node operator in legal trouble, connected Weber with Julius Mittenzwei, a lawyer and member of the Chaos Computer Club, a Germany-based hacker group dedicated to the freedom of information.

Things soon became much more complicated.

“Through a face-to-face conversation with someone familiar with the case, I was told that the case was very messy,” Andrew Lewman, Tor’s executive director, told the Daily Dot. “Forensics turned up possible child abuse images on the hard drives in the computers. Add to that the possibly legal weapons in the flat, and possibly legal amount of marijuana, and it wasn’t going to be a clean case of ‘just an exit node.’”

Austrian prosecutors possessed chat logs in which Weber recommended using Tor to host anything anonymously, including child pornography, a statement that Weber said did exist but was taken out of context. Weber was accused of aiding a crime in progress.

Tor’s official support faded—“We heard nothing for months,” Lewman said— but Weber’s call for online donations yielded enough to fund lawyer fees that helped him knock the sentence down considerably.

Two years later, on July 1, 2014, Weber was found guilty and sentenced to three years of probation for abetting the spread of child pornography—a relatively small sentence considering he faced 10 years in prison.

Weber continued to contribute to Tor at least a year and a half after being arrested. He took down his exit nodes but ran major middle, bridge, and entry nodes—all of which are much less susceptible to legal action.

Introducing human error

In 2011, the Deep Web’s first drug markets opened up for business.

Silk Road, Black Market Reloaded, and the Farmer’s Market transformed the illicit goods industry within months of migrating to the anonymous Tor network. While the markets flourished quickly, the arrests actually began quietly the same year that Silk Road started.

An as-yet-unnamed confidential source gave federal investigators a crash course in how Silk Road worked in November 2011. He also gave them access to a vendor’s account, as well as the names and addresses of Silk Road customers around the world.

In 2012, the arrests became more prominent.

Jacob Theodore George IV, a major early heroin vendor known as “digitalink” on Silk Road, was arrested in January 2012, after his packages had been repeatedly intercepted for at least the previous six months. George knew about the interceptions, but he bragged online about how he had sweet talked his way out of any problems. Some buyers were unconvinced—more than one called him an idiot and predicted his imminent arrest—but digitalink kept shipping heroin and a handful of other drugs out to customers until the cops knocked down his door.

Over the next two years, dozens of dealers and customers were arrested for drug operations on the Deep Web. The cause wasn’t Tor itself—the most obvious common denominator—it was human error.

George’s shipments, and those by others like him, were caught and flagged while they were being mailed. Many had poor “stealth” for their packages, making them easily detected by postal worker sand drug dogs.

Even some of Silk Road’s biggest operations have been brought down via the postal service. Deep Web heroin kingpin Steven Lloyd Sadler and his partner-in-crime girlfriend, Jenna White, sold heroin, cocaine, and meth by the bundle on the Deep Web, shipping high-quality product at premium prices to earn over $105,000 per month.

But White was flagged by postal workers after she parked in front of security cameras at post offices, bought masses of stamps at once, and visited often enough to be identified as the woman with handwriting identical to those found on intercepted packages containing heroin.

Deep Web drug dealers don’t just make mistakes in the regular mail. They also make them in email.

In April 2012, the Farmer’s Market (TFM) was shuttered and its administrators arrested after a two-year investigation by the Drug Enforcement Agency.

TFM, which had been operating for at least six years online, had only recently made the move to Tor in order to improve security. TFM’s owners also used Hushmail, a Canadian operation that advertises itself as powerfully encrypted private email. The problem was that Hushmail themselves could decrypt the emails, so when police subpoenaed the company, every single email was an open book for law enforcement.

When Silk Road fell in 2013, the arrests of dozens of Tor users for drug offences were made public all at once. Many wondered, in the wake of Snowden’s National Security Agency leaks, if the program itself was broken.

Even today, roughly one year after Ross Ulbricht was apprehended, there are still many unanswered questions about his arrest. The FBI claims that the black market accidently gave up its location due to trivial but profound mistakes made by Ulbricht when he configured Tor for the hidden service he operated. Critics among the information security community, however, believe the FBI hacked in by attacking Silk Road with unexpected commands and forcing the server to mistakenly give up its location.

The speculation surrounding the specifics of Silk Road’s fall will likely remain unanswered until the trial begins in November, if not longer.

In almost all the cases we know about, it’s trivial mistakes that tend to unintentionally expose Tor users.

Several top Silk Road administrators were arrested because they gave proof of identity to Dread Pirate Roberts, data that was owned by the police when Ulbricht was arrested. Giving your identity away, even to a trusted confidant, is always huge mistake.

A major meth dealer’s operation was discovered after the IRS started investigating him for unpaid taxes, and an OBGYN who allegedly sold prescription pills used the same username on Silk Road that she did on eBay.

Likewise, the recent arrest of a pedophile could be traced to his use of “gateway sites” (such as Tor2Web), which allow users to access the Deep Web but, contrary to popular belief, do not offer the anonymizing power of Tor.

“There’s not a magic way to trace people [through Tor], so we typically capitalize on human error, looking for whatever clues people leave in their wake,” James Kilpatrick, a Homeland Security Investigations agent, told the Wall Street Journal.

Tor isn’t perfect. It’s an ambitious piece of open-source software run off of grants and donations that is constantly under scrutiny from all corners. The regular security updates and constant work that goes into the product prove that there is still work to be done.

Tor’s greatest Achilles’ heel, however, remains its users.

When Tor users are arrested, “it usually does not involve the core technology being cracked or being hacked in any way,” Nik Cubrilovic, an Australian cybersecurity consultant, recently told Politico. “It’s usually something else.”

Hackers with a badge

On the morning of Aug. 3, 2013, every site hosted by Freedom Hosting crashed.

Freedom Hosting was the most popular hosting service on the Deep Web, described by the FBI as the “largest facilitator of child porn on the planet.” It was even the target of attacks from groups like the hacker collective Anonymous.

The fall of Freedom Hosting—a case that is still in its early stages—is one of the big question marks in Tor history. The case has moved slowly due to its international nature, and police have revealed precious little about how they found Freedom Hosting and arrested its alleged owner, Irishman Eric Eoin Marques.

What we do know, however, is what happened next. Once authorities had control of Freedom Hosting and the over 100 popular websites it hosted, the FBI launched a custom malware attack against Tor users designed to identify anyone who visited child porn sites. The malware, included in a hidden iframe tag, loaded a strange bit of Javascript that exploited a critical memory management vulnerability in Firefox. The bug had been fixed and patched almost two months prior, but whoever didn’t upgrade their browsers would be susceptible.

Such efforts by the FBI are standard procedure. Documents from the Edward Snowden leaks revealed the NSA targeted Tor users who didn’t keep their software up to date—using custom-built tools with the codename “EgotisticalGiraffe.” Instead of attacking the Tor network directly, the NSA targeted older versions of the Firefox browser utilized by careless Tor users.

“We will never be able to de-anonymize all Tor users all the time,” the leaked NSA documents state. With malware and manual analysis, “a very small fraction” can be unmasked, the documents allege. However, the agency has never deanonymized a specifically targeted user.

The problem , as far as can be gleaned from the information we have, hasn’t been the Tor software. It’s been those who haven’t kept everything up to date.

Now, the Justice Department is looking to take a more proactive approach. A new proposal from the Justice Department to amend Rule 41 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure aims to make it much easier for police to legally hack into computers that use anonymity networks both domestically and abroad, granting American police unilateral power to hack foreigners regardless of any potential violation of another nation’s sovereignty.

“We think legitimizing a process that attacks anonymity and has the potential to allow the government to engage in extraterritorial searches is very problematic,” Electronic Frontier Foundation staff attorney Hanni Fakhoury told the Daily Dot. “While we know the government has engaged in these sorts of searches in the past, codifying its ability to do so invites the government to use these techniques more frequently.”

The actual language of the proposal would make hacking anyone using anonymizing technology acceptable “because the target of the search has deliberately disguised the location of the media or information to be searched.” Critics like Fakhoury are concerned that such techniques would become standard practice instead of a last resort, and suggests that “requiring ‘exhaustion of other techniques’ or ‘necessity’ may … narrow the scope of this search power.”

The future of police work on the Deep Web will inevitably involve a rising tide of hacking from both sides of the fence. If this proposal gains traction, Tor users around the globe may face newly empowered American police waging a borderless cyberwar against them.

Photos via Wikimedia and The Usual Suspects | Remix by Max Fleishman