The Department of Homeland Security shut down famed Deep Web drug market Silk Road, a site that allegedly facilitated more than $1.2 billion drug-related transactions since opening January 2011. Alleged proprietor Ross William Ulbricht, 29, was arrested on Wednesday in San Francisco and charged narcotics trafficking, money laundering, and computer hacking.

Personally, the cultural takeaway buried beneath the hard news was just how ordinary parts of Ulbricht’s back story sounded. Take a look at his LinkedIn profile. Now check out his Facebook pictures: He’s playing beer pong and going to Crazy Hat Parties.

Turns out Ulbricht grew up in Texas near where I live. Some believe he went to this well-to-do public school west of Austin, about six miles from my house. Considering his age, that’d put him in the same exact class as a few of the friends I’ll see at Austin City Limits Music Festival this weekend.

The funny thing about all this is that, through transitive property, I’ve encountered certain drugs that were purchased through Silk Road’s supposedly anonymous black market, accessible only through the free browser Tor. My buddy Wayne (not his real name) used to patronize the site all the time—to the tune of $35,000 worth of transactions, the sum of which wrought him vacuum-sealed packages of all sorts of colorful drugs.

“In the same week, I might have received an ounce of psychedelic fungus from Oregon, a quarter-pound of beautiful marijuana from Canada disguised as powdered eggs (complete with fake labels and arriving in sealed tin cans), and MDMA crystals the size of my thumb from the Netherlands,” he told me.

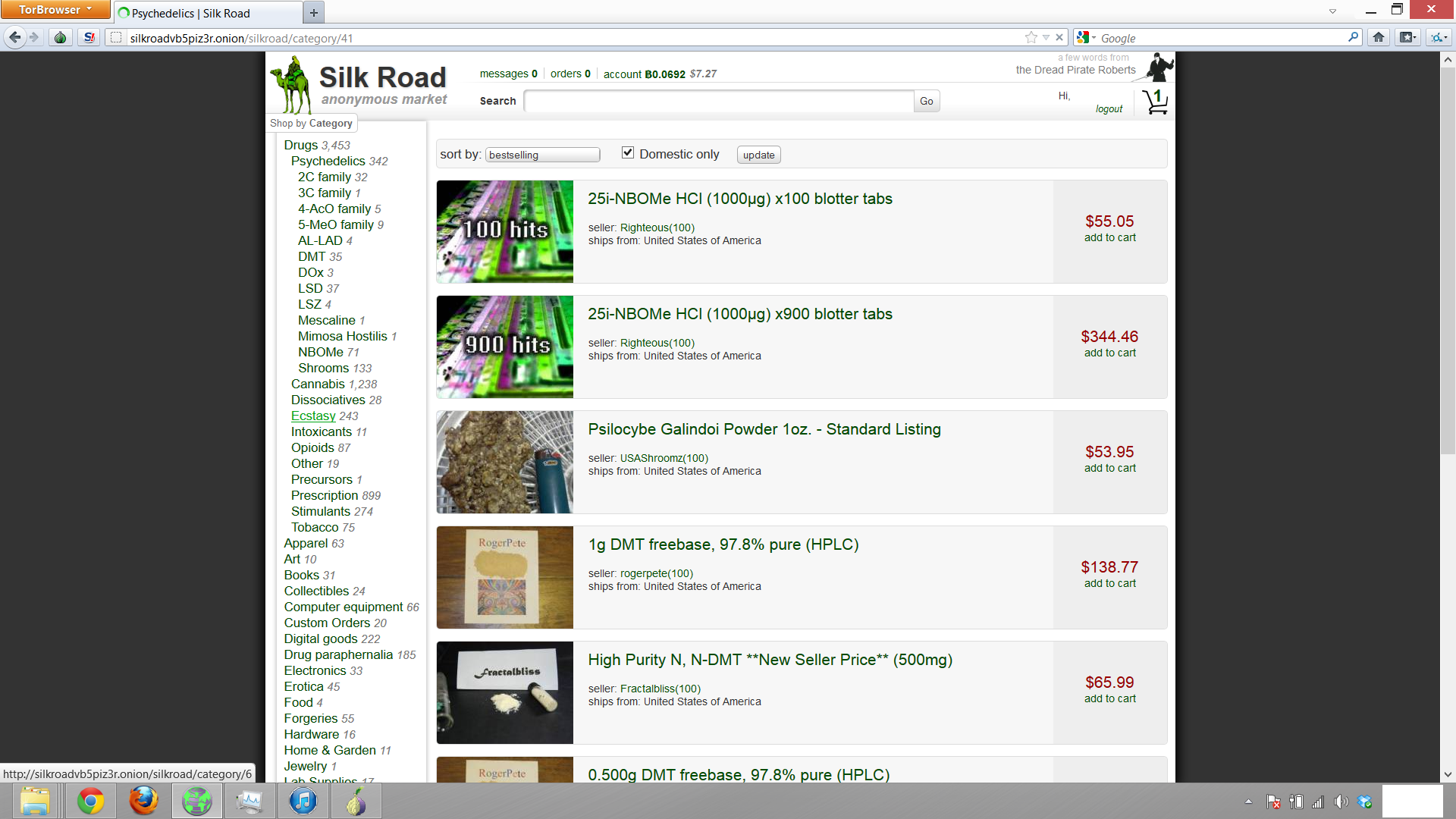

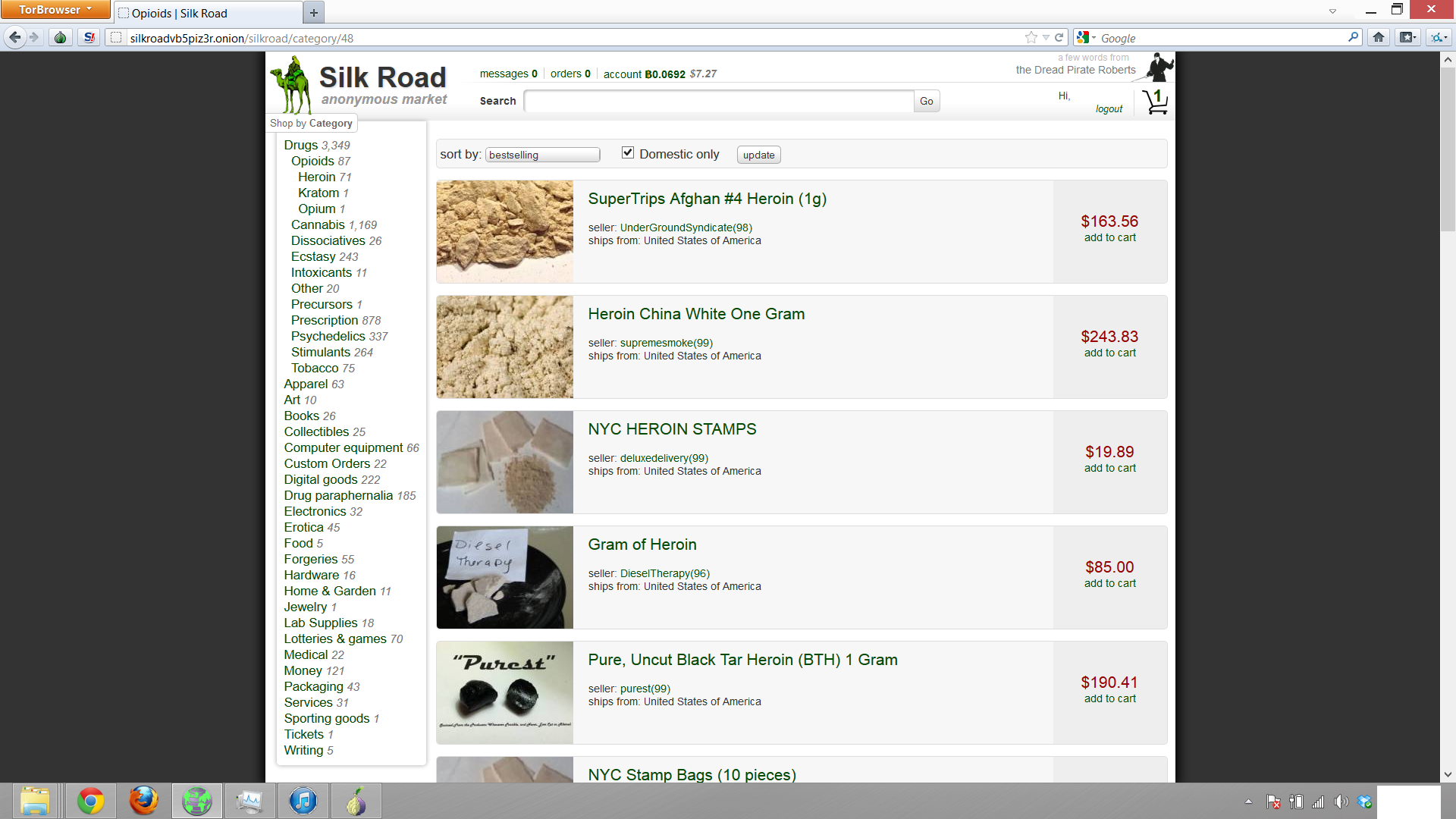

Examples of the illegal drugs previously available on the Silk Road

Wayne learned about Silk Road from the New Yorker. In the fall of 2011, the magazine published an article entitled “The Crypto-Currency” about the encrypted digital tender known as Bitcoin. The article described the currency’s mysterious origins and enigmatic creator, and it foreshadowed the real-dollar value and wild swings that would ultimately make Bitcoin an interest of the Department of Homeland Security in the summer of 2013.

“The method and technology of Tor is largely meaningless to me, and a quick glance at Tor’s Wikipedia page was all the assurance I needed to proceed,” Wayne said. “Frankly, I was so excited to buy drugs online that anonymity hardly mattered anyway. I learned how to obtain bitcoins in the same way, and with minimal difficulty, I created a Silk Road account and deposited my first bitcoin.”

Wayne frequented the site for two years before cashing in his bitcoins and getting the hell out, but he equates the whole thing to online shopping at Amazon: “There’s a price listed. You have money in your account. You enter in your mailing address and click buy.”

There was a scam artist for every honest businessman out there, he stressed, but that’s city living for you. I know a guy who lost $100 doubling up on a Manhattan street corner game of three-card monte last month. At least Silk Road used paid moderators to resolve disputes and ban vendors “who are not upholding an honest standard” for the community.

Wayne had a full-time job the whole time that he used the site, not to mention friends, family, a girlfriend, and hobbies. He’s one of the oldest friends I have, and he maintains that Silk Road was not about bad guys doing bad things under the veil of Internet confidentiality, but rather a necessarily anonymous network of true-blue libertarians who were embracing the full DIY potential of the Deep Web. He likened the community there to that of the classifieds hub Craigslist, travel site Airbnb, and homemade marketplace Etsy, sites that are “revealing the Internet’s true promise of unconditional individualism.”

That libertarian spirit has some limitations. Wayne’s time on the site coincided with the introduction of the Armory, a poorly received munitions store on Silk Road that specialized in guns, knives, and explosives. The Armory lasted only six months, shutting down under the auspices of poor revenue. The people had spoken: On Silk Road at least, they weren’t down with distributing guns in an anonymous manner.

Recreational drugs are another matter entirely, Wayne would argue. If you’re curious or into them, you’ll find drugs whether Silk Road exists or not. Might as well get it delivered to your doorstep in a tin can package disguised as powdered eggs, the logic goes. The dealer might have your address, but it’s a simple transaction and mutually beneficial. Besides, the dude probably lives in Holland, and you’re in Florida (or wherever), and the dealer’s already got your bitcoin in his virtual pocket anyway.

The business boils, quite simply, down to price points and positive reviews. It’s nü-local, Wayne said, a hub “where consumers can feel confident that what they’re purchasing is reflective of their own unique personalities.

“The ability to display and conduct one’s entire life online circumvents inefficiency and the traditional methods of acquisition, promotion, and validation,” Wayne said.

Silk Road is dead. Long live Silk Road.

Illustration by Jason Reed