The millions of volunteers who write and edit the world’s biggest encyclopedia are usually faceless. But not Legolas2186.

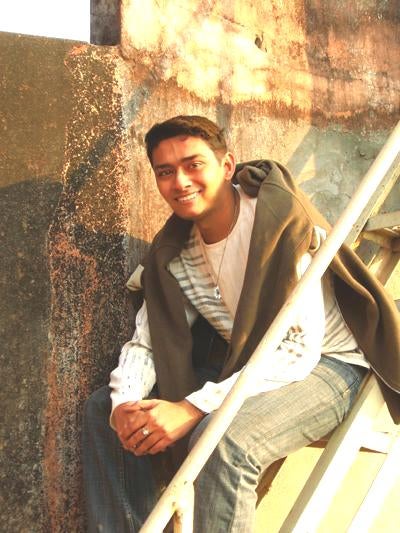

Lanky, with neat-trimmed hair and a bright smile, Legolas2186 greets visitors to his Wikipedia page with a photograph and an ebullient caption: “The one and only MEEE.” Below, his page unfurls with the gaudy grandeur of a high school student’s trophy room.

First up is an award—or barnstar, in Wikipedia parlance—for his “tireless contributions” to the encyclopedia. Scroll down and you’ll see another for “diligence” and another calling him a “superior scribe.”

“There is no point in me saying ‘keep up the excellent work,’ because I and many others know you certainly will. Thank You!” Wikipedian MelbourneStar gushed.

Indeed, by all appearances Legolas2186 was a model, even exemplary, Wikipedian. In his five years as a volunteer editor, he’d racked up more than 36,000 edits, mostly on articles relating to Madonna, Lady Gaga, and other pop culture phenomenons.

And he was well-rewarded. The community elevated 95 articles he worked on to “Good Article” status, an honor bestowed on less than 1 percent of the encyclopedia’s 4 million English language articles. Another two were crowned with an even rarer status: “Feature Articles,” the type of entry that’s featured on Wikipedia’s front page, some of the most valuable real estate on the Internet.

But like his parallels in news media, Jayson Blair and Stephen Glass, Legolas was weaving together a portfolio of success with a web of cleverly constructed lies, false sources, and invented quotes. An investigation led by an enterprising team of Wikipedia editors dug up dozens of fabrications perpetrated by Legolas, who was later banished from the site.

Legolas2186 is hardly the first hoaxster to fool Wikipedia. But his case shows the urgency with which the encyclopedia needs to modernize and adapt, as the editorial core it relies upon to fend off the Internet’s unrelenting wave of trolls and liars grows ever smaller.

***

Wikipedia rules the Internet’s information ecosystem. Run just about any word through Google and the search engine will respond with a Wikipedia link somewhere high on the page. About 470 million people visit the encyclopedia every month, making it one of the top five most-visited sites in the world. With 100,000 active users and more than 23 million articles, it’s the crown jewel of crowdsourcing. It dominates through sheer ubiquity.

The key to that success is hardly a secret. Wikipedia lets everyone in. Anyone with an Internet connection can become an editor. And when you open your door to the world, it’s no surprise someone graffitis the walls.

Three weeks ago, the Daily Dot reported on an elaborate work of fiction called the Bicholim Conflict, a 17th century war that raged across the Indian subcontinent between mighty Maratha Empire and colonial Portugal. Wikipedia editors removed the hoax as soon as it was discovered—more than five years after it was created.

Yet as long as that may seem, the Bicholim Conflict was only the eighth longest hoax in the site’s history.

Take Gaius Flavius Antoninus, for instance, an imaginary assassin of Julius Caesar who existed on Wikipedia for eight years. There’s also Chen Fang, a Harvard university student who declared himself mayor of a small Chinese town on its Wikipedia page. He held that title for more than seven years, until he blew his cover by bragging about it to Harvard researchers.

But Legolas2186’s activities were far more insidious: He wasn’t just tagging the walls with spray paint—he was knocking out stones from the foundation. And like Stephen Glass, The New Republic reporter who slipped pure fiction past his editors by falsifying his notes, it’s easier to corrupt the system when you know it from the inside.

It took five years for Wikipedians to finally discover something was wrong with Legolas, when the accolades on his user page started turning into probing questions. On Feb. 15, 2012 Wikipedian Binksternet noticed something off about an article Legolas2186 had nominated for “Good Article” status. Soon, Binksternet and about five other editors began combing through his vast edit history, looking for citation irregularities.

They found them by the droves—and not on obscure topics like the Bicholim Conflict or tiny Chinese villages. Legolas2186 seemed to hunger for the Wikipedia limelight.

He targeted his most pernicious lies at pages he hoped to promote, either to Good Article or Featured Article status. One of his biggest successes, the site’s main Madonna article-—which he helped promote to Featured Article standing—sees roughly 15,000 visitors every day and is the one of the 500 most-trafficked pages on the site.

Most of Legolas2186’s fabrications were small things, insubstantial quotes and details and facts whose significance on a micro-level aren’t immediately obvious. But taken as a whole, they represent a fundamental undermining of Wikipedia’s core values and purpose.

They are as perplexing as they are infuriating.

Take, for instance, his fondness for music magazine Blender. He littered Wikipedia’s Madonna articles with quotes from a Blender journalist, Tony Power, using his expert opinion to fill out articles for songs like “Material Girl,” “Papa Don’t Preach,” and nine others.

All of those songs were released in the 1980s. Blender, the first all-digital CD-ROM magazine, launched in 1994.

Once, Legolas invented a Rolling Stone article so he could insert a seemingly pointless fact about Lady Gaga’s wardrobe choice for her Monster’s Ball tour. In another case, he bizarrely took a journalist’s words and attributed them directly to Madonna.

“There is the sense that Madonna, isolated by fame and shaken by the failure of her marriage, is reaching back to the stability of family roots,” author Lucy O’Brien wrote in her book, Madonna: Like an Icon.

On Wikipedia, Legolas2186 changed the quote to this: “Madonna explained that ‘isolated by fame and shaken by the failure of my marriage, I could only reach out to the stability of my family roots… ‘”

In response to the falsified quote, one Wikipedian wrote: “I find the suggestion that an editor has fabricated references and a quote from a living person to be very troubling.”

Legolas2186’s dozens of fabrications, listed here, spread like a parasite to versions of the articles in other languages. But they don’t paint the full picture of Legolas2186’s time on Wikipedia. As he was dropping lies, the 28-year-old from India, who speaks Bengali as his first language, was also editing with care about subjects he approached with genuine passion. He created a special project to clean up and better organize the encyclopedia’s entries on Lady Gaga, for example.

“I don’t have any intention to be an admin now, but sometimes I really feel like being one, just to stop [anonymous users] and the users who vandalize and enter misinfo in the Gaga articles. Especially the fans,” he wrote.

He added as a personal aside: “Lady Gaga’s songs are good but what I really like about her is her innovative style. She’s like Madonna in her old days.”

***

Numerous studies have shown that vandalism—sneaking curse words or lies or libel into articles—gets cleaned up pretty quickly on Wikipedia. In one study from 2007, researchers at the University of Minnesota found 42 percent of false information was cleaned up almost “immediately.” Of course, that still leaves 58 percent of falsehoods to linger.

Small lies linger, and they matter—especially when they cross paths with important events. Earlier this year, British Lord Justice Brian Leveson copied a fact he learned from Wikipedia into the pages of a major judicial inquiry into Britain’s phone-hacking scandals. Leveson’s embarrassing gaffe, reported widely in the British press, misidentified a 25-year-old Californian, Brett Straub, as a founder of a major British newspaper. Straub hadn’t even been born in 1986, when the paper was founded. His college buddy had copied his name into the entry as a prank years ago, then completely forgot about it.

Writing in The Atlantic last year, Yoni Appelbaum pinned Wikipedia’s hoax-discovery problem partially on structure. Appelbaum was looking into similar hoaxes perpetrated by undergraduate students at George Mason University. In 2008, as part a project for the class “Lying about the past,” professor T. Mills Kelly encouraged his students to create a Wikipedia page for a fictional pirate, Edward Owens. The hoax wasn’t discovered until Kelly himself announced it at the end of the semester, but by then the story of the Chesapeake Bay oyster fisherman, who turned to pirating after he fell on hard times, had already hit major media outlets like USA Today.

A similar prank in 2012 went undetected on Wikipedia. But on social news site Reddit, where the link was cross-posted, users bore into the student’s well-constructed lies, which included fake newspaper clippings, fabricated images, and blogs.

They exposed it in 26 minutes.

Calling Wikipedia’s community “weak,” Appelbaum observed that discussion on Reddit is funneled to a single location and new comments surface quickly, usually based on merit. Reddit rewards users who contribute, which in turn encourages skeptics. Parroting the facts in an article won’t help you stand out in the rush for upvotes. Proving them wrong will.

By contrast, on Wikipedia discussion is decentralized. “Although everyone views the same information, edits take place on a separate page, and discussions of reliability on another, insulating ordinary users from any doubts that might be expressed,” Appelbaum wrote.

“Weak” isn’t exactly the right word. To the extent that its users hold a shared sense of purpose and online identity, Wikipedia’s community is very strong. But the structural and technological components holding it together are indeed very weak. The site’s internal communications tools are wallowing somewhere in the Internet equivalent of the 15th century.

That doesn’t just slow down the discovery of hoaxes, it scares people away. And meanwhile, pranksters like Legolas strain the time the site’s editors do have—all of which only exacerbates Wikipedia’s unprecedented editorial crisis.

“Wikipedians want to make wikipedia better by contributing to articles,” Jay Walsh, Wikipedia’s communications head, told the Daily Dot. “The custodial work, preventing vandalism, does distract from the really important work.

“We understand that when a group of highly active editors gets small, then you’re going to lose some of those people who would do the day to day page-patrolling, or the in-depth analysis of page references.”

Study after study has shown that Wikipedia’s editors are disappearing. One published earlier this month in The American Behavioral Science Journal, found that English Wikipedia editors had declined 30 percent from 2006 to 2011, from 50,000 to roughly 35,000.

Wikimedia Foundation, the group that runs Wikipedia and its sister projects, is well aware of the editor crisis. The Foundation’s 2012-13 annual report plan calls the problem “intractable,” highlighting it as one of the organization’s three main priorities for the coming year:

“Our projects’ success depends on a thriving, diverse, healthy editing community, and yet editor numbers are declining.”

The causes, the report says, are “insufficient site usability and discoverability of fun stuff to do” and the “declining support, hospitality and appreciation offered to newcomers by the community, as well as a growth in the editorial learning curve for newcomers due to increasing policy complexity.”

The Foundation’s solution is to chip away at the problem from a variety of fronts. This includes recruitment campaigns in Brazil and India; a kind of mentoring program for new editors, called the “Tea House;” and a much-needed overhaul of the site’s editing software, which would make writing a lot more intuitive. The foundation has more radical ideas in the works as well, most notably an overhaul of its backend communication tools that would make editing the site a lot more social and fun.

Action needs to happen sooner rather than later. Wikipedia added 3.5 million articles last year alone. As editor numbers shrink, the encyclopedia—and the Internet at large—only grows, creating a gap that will become only more difficult to close.

***

I asked Doctor Charles Ford, a psychology professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham who’s written books about compulsive liars, what might have motivated Legolas2186 to lie so frequently and effortlessly. Generally speaking, Ford said, compulsive lying has ties to either a learning disorder or narcissism (though he emphasized he couldn’t speak specifically about Legolas2186, having never met him).

“One may assume a sense of power from being able to fool others, and the [more] you fool the more powerful you are,” Ford wrote in an email. Other compulsive liars have a warped sense of reality because they believe themselves to be the center of the universe.

“They then define what is real and not real.”

Photo via Wikipedia

Is the smiling young man at the top of the Wikipedia page really Legolas2816? Or is it an image of the person he wanted to be?

He didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment and hasn’t been seen on Wikipedia since early last year.

At the bottom of his talk page, his legacy is marked with a single note:

“This account has been indefinitely blocked upon review of outstanding claims of fabrication of sources and quotes. Damaging the integrity of Wikipedia is not acceptable behavior.”

Illustration by Jason Reed