At the Republican National Convention in Cleveland earlier this summer, the vendors selling merch had a pretty good idea about what the throngs of conservative convention attendees wanted to buy. Anything with the official slogan of 2016 Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump, “Make America Great Again,” did well, but the biggest sellers were buttons about Trump’s Democratic rival with a singular, provocative message: “Hillary For Prison.”

That message reverberated inside the convention hall as well. The audience would regularly interrupt speeches with chants of, “lock her up,” calling for Hillary Clinton‘s imprisonment for a variety of crimes ranging from operating a private email server while running the State Department to the deaths of four American citizens during a 2012 attack on the U.S. embassy in Benghazi, Libya. “Tonight, as a former federal prosecutor, I welcome the opportunity to hold Hillary Rodham Clinton accountable for her performance and her character,” intoned New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie.

“Lock her up,” the crowd chanted in response.

“Give me a few more minutes,” Christie grinned. “We’ll get there.”

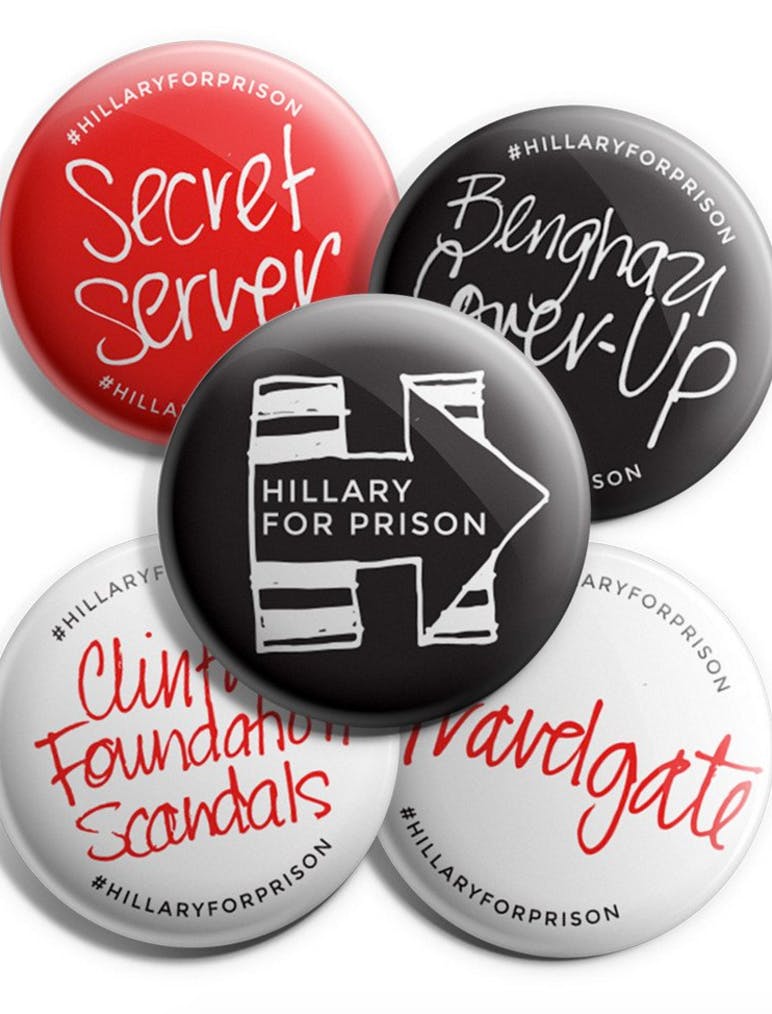

Calls to send political rivals to jail, which are largely unprecedented in this history of American presidential politics, have since been officially adopted by the Trump campaign itself. Trump’s campaign website is now selling multiple items of “Hillary For Prison” merchandise. A three-piece set of “Hillary For Prison” buttons currently retails for $6; the five-piece “Hillary Scandals” set goes for $10, and there is an assortment of anti-Clinton T-shirts for $20-$35.

“There’s only one place for Hillary Clinton and it’s not the White House,” reads the description of one of the two button collections advocating Clinton’s imprisonment.

“The only pantsuit she should be wearing,” exclaims the description a shirt being sold on the site. “Show you’re in the know when it comes to Hillary.”

Trump’s position on calls to have Clinton imprisoned seems to have evolved in weeks. At a press conference shortly after the conclusion of the conventions, Trump said he initially discouraged the “lock her up” chants, calling them a “shame.”

As time wore on, however, Trump noted his attitude was shifting. “You know it’s interesting. Every time I mention her, everyone screams ‘lock her up, lock her up.’ They keep screaming. And you know what I do? I’ve been nice,” Trump said during an event in Colorado Springs, Colorado. “But after watching that performance last night—such lies—I don’t have to be so nice anymore. I’m taking the gloves off.”

According to Steve Jarding, a lecturer at Harvard’s Kennedy School Government and a founding partner of the international political consulting firm SJB Strategies, there’s little precedent in U.S. presidential politics for Trump’s calls for the jailing of his electoral rival.

“Sometimes there will be groups that start movement, whether it’s somebody trying to paint someone as a criminal or, in this case, saying someone ought to be in jail,” he said. “Normally, it would be a third-party group or, rarely, it would be a party organization. But the thought that a presidential candidate’s entity in and of itself would actively promote such a thing is without precedent.”

At times in American history, prominent politicians have been thrown in the jail for their political beliefs. Five-time Socialist party presidential candidate Eugene Debs was sentenced under the Espionage Act to 10 years in prison for his opposition to U.S. participation in World War I, calling for people to refuse to avoid the draft for ideological reasons. While Debs, who was granted clemency in 1921, had drawn the personal enmity of President Woodrow Wilson, Debs’s presidential runs, even that their most successful, only captured a single digit percentage of the national vote. Wilson had far more formidable political foes than the pioneering labor organizer, who didn’t pose a serious threat to his electoral future. Between Trump and Clinton, the calculus is very different.

Dr. Ray Smock, director of the Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History at Shepherd University, notes that, while a candidate selling campaign merchandise calling for his rival’s arrest is certainly new, it’s part of a long American tradition inflammatory political rhetoric.

“All the way back to the first campaigns … people have been called everything under the sun,” noted Smock, the former official historian of the United States House of Representatives. “Trump goes around calling everybody weak; there was a newspaper that was particularly against George Washington that was always saying that he was a traitor, he was weak, he had no qualities of leadership. That kind of thing goes back to the beginning. … Nasty campaigning is a part of American history, whether we like it or not.”

Smock pointed to another example of pointed campaign merchandise—a widely circulated poster show a pregnant black woman and bearing the innuendo-laden slogan “Nixon’s the One.”

He also pointed to a piece of merchandise distributed this election cycle by the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee with a cartoon of Trump’s face in profile surrounded by the words “Stop Bigotry,” effectively calling Trump a bigot.

Nevertheless, Smock doesn’t see the vitriol coming from both sides as equal. The rhetoric from some GOP officials in recent years, he argues, has shifted into new territory. He pointed to recent statements from a Republican legislator in the West Virginia House of Delegates who, in the wake of FBI Director James Comey’s announcement that Clinton would not face charges in her State Department private email scandal, said, “Hillary Clinton, you should be tried for treason, murder, and crimes against the US Constitution…then hung on the Mall in Washington, DC.”

While advocating for the personal destruction of political foes may rile up the voter base, Smock believes it drives a wedge between the parties that makes it difficult for government to work after election day. “You get to the point where you paint your opponent as the devil. Trump has called Hillary the devil. How do you compromise with the devil?” Smock wondered. “If the art of politics is compromise, which I do believe, once you demonize your opponent to the point where they’re not worthy, then the political process itself suffers no matter who wins. Then you can’t govern.

“These are all tactics of a campaign,” he added. “The tactics of governing are completely different than the tactics of a campaign. You cannot govern from such polarized positions.”

Representatives from the Trump campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

Correction: An earlier version of this article cited the previous name of the Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History. We regret the error.

Contact the author: Aaron Sankin, asankin@dailydot.com