Does riding the subway to work cause more stress than walking an extra 15 minutes? How do doctors’ stress levels fluctuate on a daily basis? Is it possible for an entire city to destress?

These are some of the questions that Boston-based startup Neumitra could answer. The company founded by neuroscientists created a wearable that monitors stress, and it’s kicking off a comprehensive stress study early next year that will look at an unprecedented set of data: A city’s stress levels.

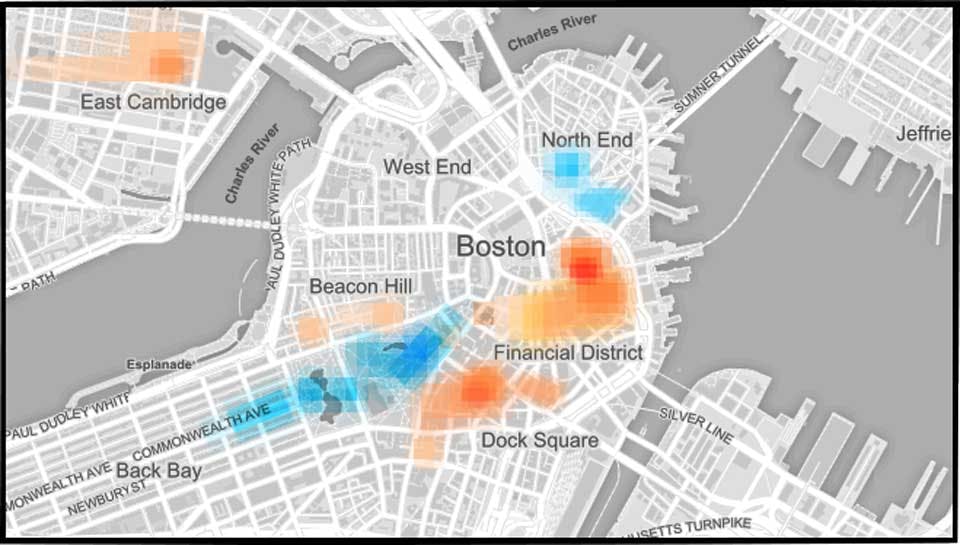

“One of the clearest deliverables for us will be a real-time, dynamic map of the city of Boston so that anyone can come and understand how do commutes, types of commutes, and places, affect the city of Boston,” Rob Goldberg, neuroscientist and founder of Neumitra said in an interview with the Daily Dot. “All the way to different demographic factors, like whether it be more or less stressful places for women and men, lower socio-economic status, to different ethnicities or racial groups.”

The United Nations estimates that 66 percent of the world’s population will live in cities by 2050. And cities are home to people more prone to psychological disorders, many of which are affected or caused by stress.

City-dwellers have a 21 percent increased risk of anxiety disorders, and 39 percent increased risk of mood disorders, The Guardian reports. But Goldberg said it’s not clear whether cities are the cause of stress, or that more stressed out people move to or live in cities.

This is the kind of data that could be gleaned as Boston residents connect themselves to Neumitra’s devices, and provide that health data to the company and participating organizations.

Goldberg and his colleagues created Neumitra in 2009 while at MIT. Initially, he said, the device was designed to measure and manage anxiety, but because there are many similarities between anxiety and stress, and people didn’t respond well to the term “anxiety,” the goals changed. (For instance, Goldberg said Type A men have trouble thinking they have anxiety.) The device and app are designed to work with wearables and apps already on the market, like fitness bands, activity trackers and calendars.

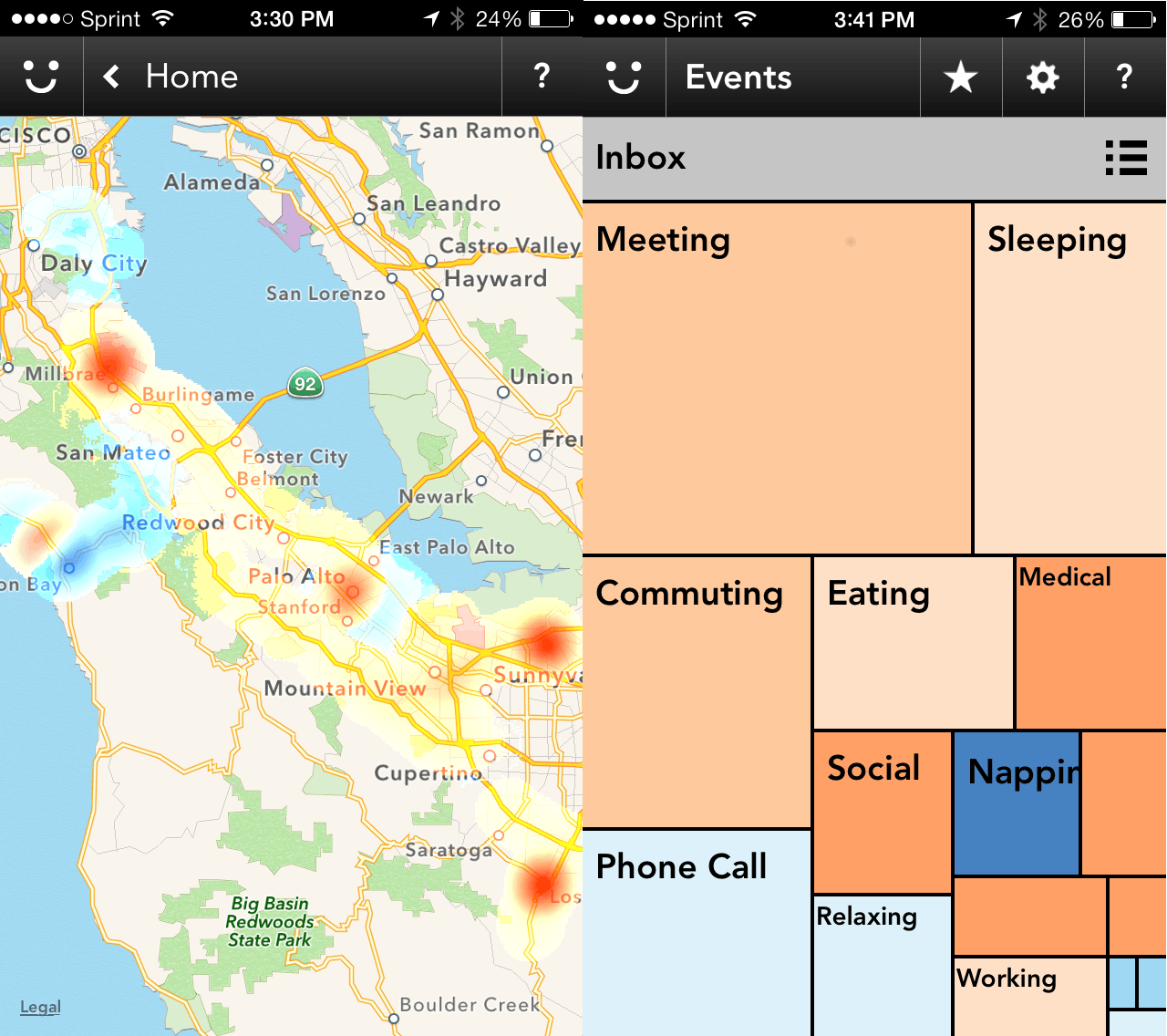

The device measures four signals to monitor the physiology of stress: galvanic skin response, which includes skin’s electrical characteristics or things like perspiration; temperature; motion; and heart rate. It collects and analyzes this data ten times per second, Goldberg said. And by integrating with your calendar and GPS, it can build a complete picture of the stresses in your life.

The initial participants include police officers, students, veterans, as well as nurses and doctors from Boston’s two largest hospitals. At its start in early 2016, at least 1,000 participants will be involved. Goldberg said the goal is to enlist 5,209 people to ultimately be involved for a prolonged period of time, a number that mirrors the Framingham Heart Study, a research effort in Massachusetts that began in 1948. The study was groundbreaking at the time, and monitored factors and characteristics of cardiovascular disease in 5,209 men and women, and it continues to this day.

By taking a look at high-stress jobs like those in the medical field, both Neumitra and the hospitals involved will be able to better understand the mental health of healthcare workers.

“I have not seen this type of study before in the literature. It adds a lot actually,” Dr. Roy Phitayakorn, director of surgical education research at Massachusetts General Hospital, which will be participating in the study, and assistant professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School told the Boston Globe. “It’s very concerning to us because what we’ve found in our study is that people are very poor at evaluating their own stress.”

Neumitra is working with companies, healthcare and educational organizations, and securing grants from science and tech investors in order to ensure average Boston citizens perhaps unable to afford luxuries like fitness trackers—not just privileged techies—can use the devices and contribute to the study to understand their health.

“Our concern was that if we just opened up technology for people to purchase, it would be this category of sort of the worried, wealthy well,” Goldberg said. “Folks that don’t have all that stressful lives, but all do experience stress. We wanted to make sure we got a broad sampling.”

The data will provide insights that go beyond just how people feel when they’re wandering around on a day-to-day basis. It can help to document how neighborhoods sleep at night, differences in traffic and crime that affect stress and sleep, and how features within a city—like parks, subways, and pedestrian commutes—contribute to the overall health of its inhabitants.

Goldberg said that using Neumitra’s device to analyze his own stresses caused him to change his behaviors while traveling in the Bay Area. According to the data collected, driving down the 280 freeway was much more relaxing than the 101, and staying in Half Moon Bay was better for his brain performance than staying elsewhere in Silicon Valley. He also learned that it’s less stressful for him to walk to work than take public transportation in Boston.

When the company’s product is available to the public early next year, people will have the option to share their data with Neumitra to contribute to the stress study. Like Jawbone’s data that provides insight to the most active cities around the world through analyzing user activity, Neumitra could eventually provide similar data in regards to stress.

Goldberg hopes that, like the Framingham study, Neumitra’s efforts can be ongoing, and data collected could give people and physicians a better understanding of stress. On a very basic level, realizing how, when, and why stress affects people can change behaviors for the better.

“We really need to just be more empathetic to each other, and we think data of this type has that potential. You can imagine that after the end of a long day, an automatic alert goes out to friends, and says, ‘Hey, she had a rough day, be nice,’ or to your boyfriend, ‘Hey, buy her flowers,’” Goldberg said. “We’re really trying to create an experience where we can look after each other in more empathetic ways, but it doesn’t require us to talk about it.”

As health monitors become more pervasive, using data collected through our smartphones and smart watches can provide more people with a nuanced picture of what’s going on in their minds and bodies. Already wearables are alerting people and physicians to trends such as exercising, food intake, and sleep. Wearables also impact mental health, for instance, some clinicians that work with patients who have eating disorders suggest using apps and services that allow people to track behaviors such as eating or bingeing.

But stress, unlike fitness, isn’t necessarily visible. And much of the data given to physicians and tech companies like Neumitra come from people self-reporting when they visit their doctors. Patients’ options to manage stress are often prescription drugs or psychiatric referral.

Neumitra doesn’t just track stress, but also provides people with solutions to manage stress. One of the most frequent causes of stress is lack of sleep—and the app might suggest getting a better night’s sleep if the data shows increased stress and decreased sleep.

“What if we manage our stress the same way we manage our weight?” Goldberg said. “And we take it seriously as a day-to-day problem that we really have to look after.”

The study will begin early next year, which is also when the devices will be available to purchase. Goldberg said the stress monitors will run under $250, a similar price point to the health trackers already on the market.

At first, the stress test might just look like a bunch of colors and dots on a map, corresponding to a tired doctor, or a mom who had a busy day at work. Eventually, those dots will become integral to a city map that doesn’t just show rail lines and public parks, but illustrates a city’s mental health as its residents experience stress or calm throughout the day.

Photo via Robbie Shade/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)