The FBI claims it has the two most wanted men on the Deep Web in custody and awaiting trial.

The infamous online black market Silk Road was seized Wednesday morning by the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security. The investigation unmasked Silk Road founder Dread Pirate Roberts, identifying him as Ross William Ulbricht, a 29-year-old graduate of the University of Texas.

According to the FBI’s report, Silk Road generated $1.2 billion in revenue in just over two years. Ulbricht was apprehended in San Francisco with $3.6 million in bitcoins, a digital currency of the Deep Web.

Today’s events echo the Aug. 3 arrest of Eric Eoin Marques, alleged to be the man behind Freedom Hosting, the popular host and engine of the Deep Web. Many of its websites were infected with Javascript exploits designed to identify previously hidden visitors. The FBI called Marques the “largest facilitator of child porn on the planet” and claimed he cleared $1.5 million in business in the last year.

The arrests have shaken the entire Deep Web to its core. Under the guise of anonymity provided by Tor—the gateway to sites hidden from Google searches—users had purchased illegal drugs, false identities, and weapons. It was a free-market paradise where almost nothing was off limits.

Now, there’s chaos and confusion. Patrons are scrambling, and vendors are closing up shop. The community is reeling, wondering what’s next, and more pressing—what sort of digital footprint they might have accidentally left behind.

But where some see a dead end, others see opportunity.

Rebuilding Lolita City

Freedom Hosting’s reach was vast, extending well beyond the seedy world of child pornography for which it was notorious. TorMail, long considered the most secure anonymous email service online, resided there, along with major money laundering operations, most notably the hacking and fraud forums HackBB and the Carding Forum. No arrests were made relating to any of these other websites and virtually all of them, with the exception of TorMail, have returned to business as normal.

In fact, as of Tuesday night, it seemed that a sense of renewal was finally taking hold in the hidden corners of the Deep Web. Shortly after Marques’s arrest, for example, it became known that a full backup of Lolita City, which hosted well over 1 million images and videos of underage children, was available as a torrent if you knew where to look. It reinforced the old Internet truism: once online, always online.

In the weeks following the bust, the child-pornography community began regrouping in earnest. A series of stopgap hosting machines were set up to begin rebuilding temporary websites while the search for strong and secure long-term hosting took root.

Even on the notoriously laissez faire Deep Web, that’s a tall order. Many potential hosts have obvious moral qualms with child pornography. Others don’t want to risk being targeted by law enforcement. The cost is high. In August, one potential Deep Web host told the Daily Dot that some large child pornography websites were already negotiating for anonymous hosting in the range of thousands of dollars per month. In light of Silk Road’s fall, many believe the price will skyrocket even further with the increased risk.

In an attempt to circumvent the need for hosting, some of the biggest child pornography websites online are now encouraging users to store image and video files on “Surface Web”—normal websites accessible to everyone—such as Anonfiles.com. (Here’s a heavy dose of irony: Two years ago, the hacktivist collective Anonymous launched Operation Darknet in a failed attempt to extinguish child pornography on the Deep Web. Today, pornographers use an Anonymous-branded hosting service to share their illegal files.)

Others are turning to contemporary anonymous networks such as I2P and Freenet. I2P is seen as a safer alternative because, unlike Tor’s hidden services, which do not have developers dedicated to solving their problems, I2P’s services (called eepsites) are actively developed. Freenet, by contrast, is a different sort of highly secure anonymous network in which all users share some of the encrypted data—including, no doubt, child pornography among many other things—on their hard drives.

“Good alternative for acquiring CP is freenet,” one anonymous poster wrote recently on a newly rebuilt pedophile community forum. “It’s practically a huge CP RAM disk.”

Several major child pornography sites have publicly announced plans to return quickly, although none have been updated since Silk Road was seized.

Black markets, reloaded

The buildup to the Silk Road bust has been months in the making.

The Drug Enforcement Agency appeared to have penetrated the marketplace in July, when it seized roughly 11 bitcoins (then about $814 U.S.) from South Carolina man for violating the Controlled Substances Act on Silk Road.

And just last week, Atlantis, an upstart Deep Web black market, shut down amid rumors from former staff members that law enforcement had been closing in. Owners cited “security concerns” before abruptly abandoning the service and shrinking into the shadows.

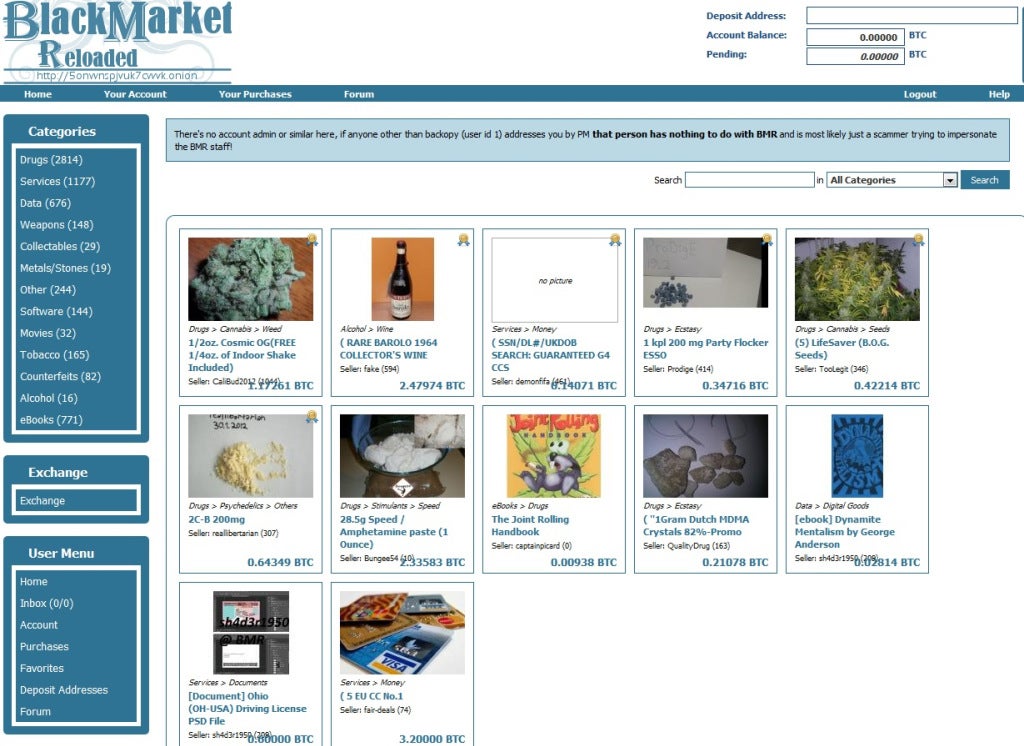

In the eyes of many, the torch has been passed from Silk Road’s Dread Pirate Roberts to backopy, the owner of Black Market Reloaded, the second most popular and profitable black market on the Deep Web.

“My sorrow for DPR’s,” backopy wrote, “he has been a great competitor all this time.”

Black Market Reloaded’s staff said they will do everything in their power to maintain business as usual.

“I’m running all sort of security checks and updates,” backopy continued, “this may cause some downtimes, sorry for that but I hope you understand how serious the situation become.”

In April 2013, backopy claimed that Black Market Reloaded did $700,000 per month in business. Now, he can expect a major influx of traffic and business over the coming days and weeks. The company’s servers are already faltering under the pressure of Silk Road’s exiled masses.

Black Market Reloaded, the second largest Deep Web bazaar.

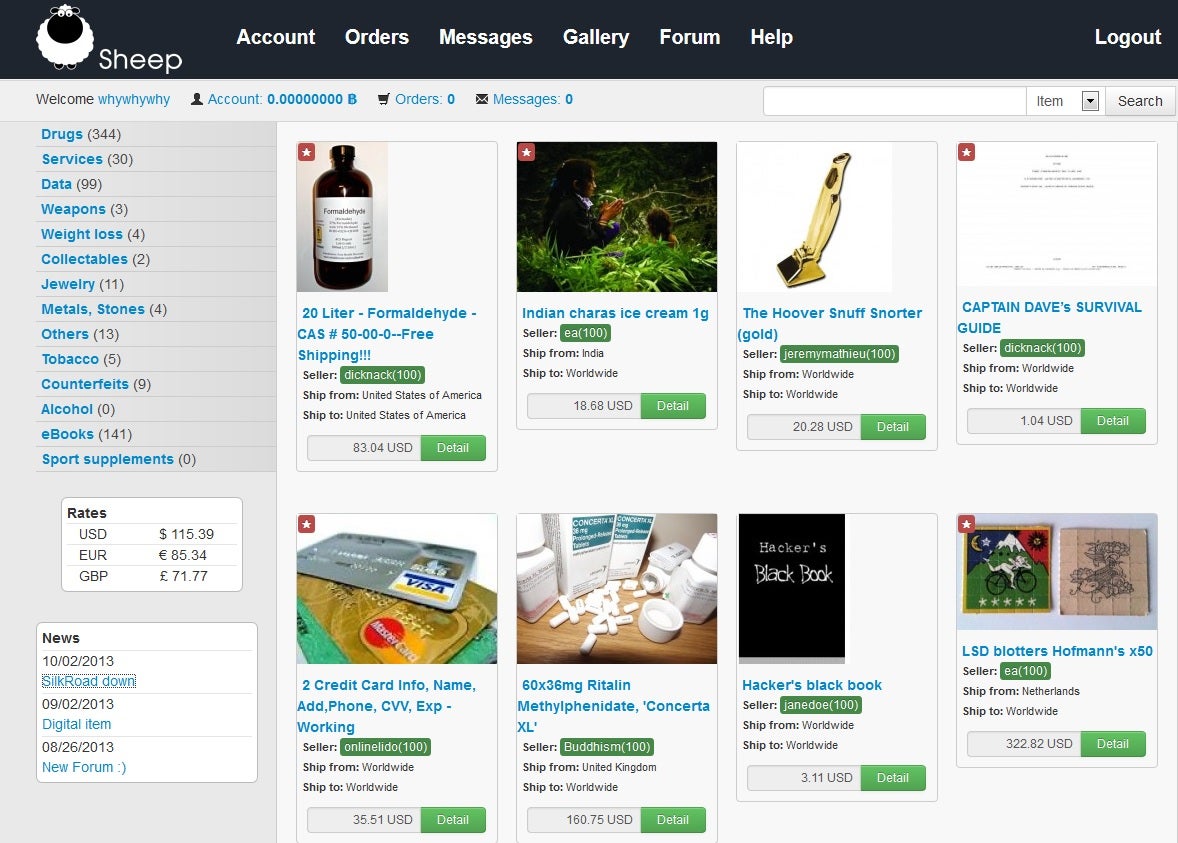

Many Silk Road vendors have also migrated over to Sheep Marketplace, yet another Deep Web storefront that specializes in illegal substances.

“For us Silkroad [was] not only competition but the main inspiration,” wrote Sheep’s owners. “We believe that replace Silkroad will not be easy. But we want our plan to continue.”

Sheep Marketplace has increased its server’s performance and put staff on notice to answer all technical support questions.

Sheep Marketplace, one of the would-be successors to Silk Road.

The major difference between Silk Road and the other markets is simple: Black Market Reloaded and Sheep Marketplace sell weapons. Two weeks ago, one of Reloaded’s top gun runners was arrested in Kentucky after a series of blunders gave away his identity.

Silk Road briefly sold weapons in 2012, but that lasted only six months. It was shut down on August 12, 2012, due to slow business. The center of the Deep Web gun trade has been Black Market Reloaded ever since.

The future of the Deep Web

The larger question facing the Deep Web, however, isn’t what services will replace Silk Road and Freedom Hosting. It’s can Tor and Bitcoin be trusted to obscure user identities.

Adrian Chen, the Gawker reporter who originally broke the story of Silk Road in 2011, believes this may be the end of the Deep Web, and Chuck Schumer, the New York senator who called for the end of Silk Road that same year, released a triumphant statement today that opened with “Sayonara to Silk Road.”

Might be time to declare the End of the Dark Net. Who really believe they can do illegal things on Tor anymore?

— Adrian Chen (@AdrianChen) October 2, 2013

Studies have shown that there are vulnerabilities in both services that can be manipulated, and according to leaked documents, joining Tor may increase the odds of the National Security Agency storing a user’s data.

“This is supposed to be some invisible black market bazaar. We made it visible,

But it’s worth remembering that Tor didn’t fail Silk Road. Dread Pirate Roberts did. He used his real name and emails in accounts related to his business. (It’s unknown at this time how Marques was tracked down.)

At this point, there is no reason to suspect that the Tor software was compromised in any way despite two of its biggest names being put in handcuffs. While this arrest will undoubtedly drive away mainstream customers for some time, it’s a virtual guarantee that the market for child pornography, drugs, guns, and other illegal products will remain active.

Outside of Silk Road, many in the Tor and Bitcoin communities are celebrating the demise of Dread Pirate Roberts. Bitcoin enthusiasts considered Silk Road a stain on the cryptocurrency’s reputation and an invitation to government action against it. The collapse of Silk Road bust led to a $20 drop in the price of bitcoins in a matter of hours, according to Bitcoin Average. (You can currently secure one full bitcoin for about $108.)

Similarly, some Tor users hope that the demise of a major black market will help refocus the world on the fact that Tor is used for much more than crime: Political activists, legitimate businesses, journalists, and governments use the service for secure communication every day.

Even if a mass exodus transpires, the billion-dollar Deep Web economy will remain a significant industry. At this very moment, Sheep Marketplace, Black Market Reloaded, and an army of anonymous hosts are considering how to rebuild the entire thing.

The Deep Web won’t die. It’s just going to plunge even deeper.

Illustration by Jason Reed