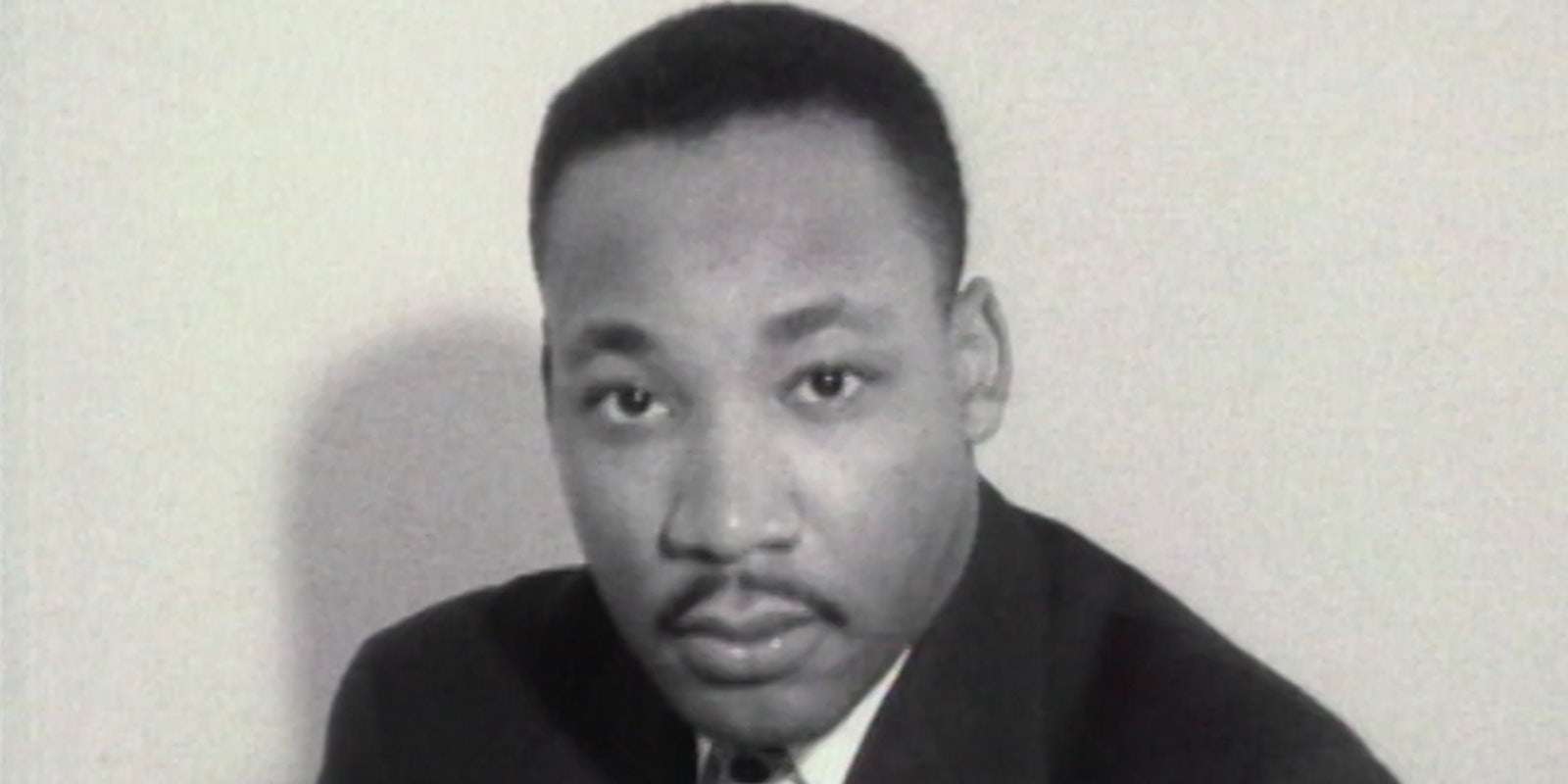

MLK/FBI is full of contrasting images, many of them put forward by history itself. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was praised internationally for his nonviolent protests during the civil rights movement and even won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, but he was often reviled at home. Just days after his famous “I Have a Dream Speech” at the March on Washington, the FBI internally called King “the most dangerous Negro in America,” King’s former speechwriter Clarence Jones recalled. And as the FBI put forward the public image that it was full of honorable heroes, the agency used its resources to take down an American citizen—and it’s likely he was far from the only one.

DIRECTOR: Sam Pollard

RELEASE: Theatrical

Sam Pollard’s searing documentary zooms in on the FBI’s contentious attempt to destroy Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and reputation amid the civil rights movement. While the FBI now sees its actions back then as shameful, ‘MLK/FBI’ is a stark reminder of how the U.S. government often views its own citizens who push for change against grave injustices.

With these visuals in the forefront, taken from extensive archival footage of King and former FBI head J. Edgar Hoover, documents, and interviews from experts and people who were there, director Sam Pollard paints a vivid portrait of two men, one who made it his mission to take down the other. Yet, at least in the case of Hoover, MLK/FBI is an often damning portrayal of the government agency that used and abused its resources in order to keep the status quo.

More than 50 years after King’s assassination, the FBI is largely ashamed of how it went after King. Former FBI director James Comey, who was among the subjects interviewed in MLK/FBI, says that the FBI’s surveillance of King was “the darkest part of the bureau’s history.” (While he worked at the bureau, he kept the FBI’s letter authorizing that surveillance on his desk as a reminder of the harm that his agency could do.) But our collective memory is long—just look at how an otherwise innocuous post from the FBI’s Twitter account acknowledging Martin Luther King Jr. Day earlier this year went over.

What MLK/FBI really hammers home is that despite its unpopularity now, how much Hoover and the FBI’s attitude toward King was a mainstream opinion, even as King was internationally lauded for his work. He was widely disliked and his push for equal rights was seen as very unpopular, despite what since-sanitized versions of King’s life would have you believe. Again and again, King had to respond to white people who fretted about the violence that occurred at nonviolent protests or wondered if Black people should wait to fight certain battles, the kinds of comments we’re still seeing now as people fret over buildings instead of protesters’ lives at Black Lives Matter protests. In response, King told naysayers to pay attention to who was inciting the violence at those protests.

Hoover had already spent decades molding the image of the FBI’s “G Men” as heroes protecting the people from threats of communism, which were then spread further via copaganda films like The FBI Story that portrayed law enforcement as saviors; at the time, Hoover was fairly popular, and the initial investigation into King was because of a potential link to communism via one of his advisors who had ties to the Communist Party.

MLK/FBI covers a lot of familiar territory over the last 13 years of King’s life, both public and more private as the FBI’s surveillance became more invasive; we were also shown how Hoover was hesitant to even investigate King’s assassination until public pressure forced his hand. We’ve already seen or read some of the declassified documents—including the FBI’s now-infamous letter to King that urged him to take his own life—in the past, but it never comes across as dull. As MLK/FBI highlighted, the FBI’s surveillance files on King won’t be unsealed until February 2027 at the earliest, so as much as we already know, we’re a few years away from a larger debate about how much more our views of King, Hoover, and Hoover’s FBI might change. We don’t see the subjects interviewed until the end of the documentary, allowing us to focus solely on their voice and what they’re conveying, especially when they’re trying to untangle particularly thorny aspects of King’s files.

With both the insight from the people featured and how the narrative of both King and Hoover are woven together, Pollard never loses sight of the larger story. There is a distinct throughline between how the FBI treated King and the many other activists fighting for equal rights or Black liberation and how it’s treating Black activists today; as Rutgers history professor Donna Murch put it, the FBI’s “most consistent campaigns were against Black people.”

Like Ava DuVernay’s Selma did a few years back, MLK/FBI starts to unpack the larger-than-life persona of King and the forces that sought to stop him. But it’s also a strikingly powerful reminder of, even as a new movement emerges, just how far a government or a federal agency might go—or has already gone—to put its own citizens down instead of embracing that change.

MLK/FBI is available to screen virtually at the New York Film Festival until Sept. 26.

The Daily Dot may receive a payment in connection with purchases of products or services featured in this article. Read our Ethics Policy to learn more.