Zoe Quinn, the developer of indie game Depression Quest, has also spent time on stage as a stand-up comic. Quinn thinks that the lessons she learned as a comedian can be applied to making video games.

She hosted a panel on the topic this week at the 2015 Game Developers Conference in San Francisco, highlighting the under-explored genre of comedy games.

While there are relatively few entries to the comedy game arena, some recent ones could include Goat Simulator, which has players running around as a destructive goat. Meanwhile, The Stanley Parable is constantly tearing down of the fourth wall. The game’s narrator yells if the player doesn’t follow their role in the story, as told by the narrator.

“You don’t really see many games that stand as a pure comedy games,” Quinn said. “Normally it’s something that a game has some elements [of comedy], but there’s very few games where comedy is their first and foremost thing, which is kind of weird. I think it’s important to talk about how we can do more of those as we go forward, because [in] every other medium, [comedy] is a genre in and of itself.”

But that might be easier said than done. For game developers to create a successful comedy game, they have to understand the mechanics of comedy itself.

“When you really boil it down,” Quinn said, “what comedy does is you expect one thing, and you get a totally different thing that’s humorous, and we all laugh. That’s generally how, just mechanically—super-distilled—comedy works.”

Comedy is about subverting expectations and that puts comedy in seeming conflict with video game design from the get-go. Video games are about systems—the player does A, and B occurs. Most gamers have an expectation of consistency. Quinn thinks developers can turn this around by designing systems that, from the ground up, are meant to support a punchline. Or even by switching out game systems as the game continues.

“A game that kind of does this is Jazzpunk,” Quinn said. “It starts out as an adventure or spy game, but then it’s all these little mini games that are gags or references.” Using different minigames allowed the developers to work all different kinds of jokes within the overarching, consistent structure of Jazzpunk.

Developers can also use the body of the game as if it were a comic, i.e. as a vehicle to tell jokes. Portal 2, a story about a test subject trying to escape from a laboratory, invokes comedy through crazy posters warning employees about potential lab accidents that probably sound insane to the player. User interfaces can be the vehicle for jokes (for example, Borderlands 2 plays around with the UI labels attached to monsters when a narrator changes their mind as to what the monster is supposed to be called).

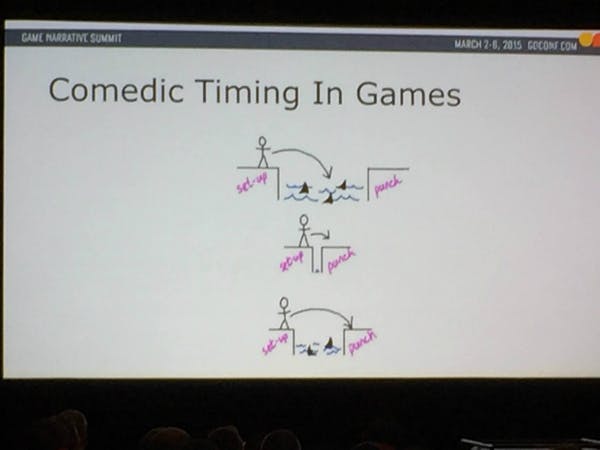

Whether someone is successful at pulling off a joke is the timing between the setup and punchline. “One joke coming from one person can land completely flat, while somebody else delivering it in a unique way can really elevate it,” Quinn said. Level design—the process that lets developers influence the path a player takes—can be a tool to control the timing of the joke.

The worst part of making comedy games might not be figuring out all the various techniques—it’s testing. Once playtesters have been through a sequence, they know all the jokes. Like watching a comedian’s set a second time, it’s just not as funny when the element of surprise is gone. All a comedy game developer can do is to test early and often, and to get as many fresh eyes on the game as possible.

“Stand-up comedians do this by testing their material at open-mic nights constantly,” Quinn said, “but you don’t have the luxury of that, because the [game design] process doesn’t lend itself to that.”

Illustration by Max Fleishman