In 2014, listening to Nickelback isn’t just a crime of bad taste. It might get you arrested. Last week, two men were detained by police after one of the officers on duty mistook their conversation about Nickelback to a reference to a “nickel sack”—or a bag of marijuana.

This isn’t even the first time the band has made headlines in the past month. In May, former Phillies MVP Ryan Howard was forced to respond to allegations that the first baseman likes the band, after fans held up a sign that read: “Ryan Howard listens to Nickelback.” Howard had a defensive nervous breakdown over it.

“Is it bad to listen to Nickelback?” Howard asked. “I mean, I’m not afraid to say that I diversify my musical portfolio. I didn’t know they could see or hear what…How do they know I listen to Nickelback? I listen to everything. I don’t know if there’s a specific song by Nickelback.”

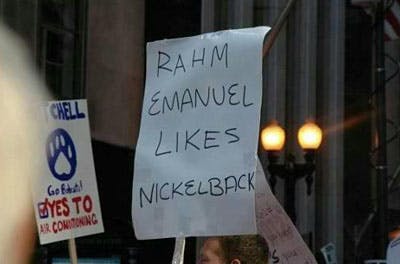

Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel faced similar accusations in 2012, when an angry Occupy protester’s sign went viral on the Internet, and Emanuel quickly renounced the band in an email. According to the Chicago RedEye, Emanuel’s spokesperson clarified the unpopular mayor’s Nickelback stance with a simple “no.”

Even though they haven’t had a hit song since 2006, when “If Everyone Cared” and “Far Away” cleared the Billboard Top 20, hatred of the band has proven to have longer staying power than Nickelback itself. The Internet’s Nickelback hatred is such a persistent cultural meme that Nickelback lead singer Chad Kroeger gets asked about it constantly in interviews—to which the Canadian offers a plaintive shrug, as bewildered as the rest of us.

Why are they hated so much? “Because we’re not hipsters,” guessed Kroeger in an interview with Philadelphia’s 106.1 FM. This is somewhat true. As a band, Nickelback is almost aggressively unhip, unwilling to adapt to musical trends outside their generic arena-rock sound; however, acts like Dave Matthews Band and Phish have stayed the same while the world changed around them, all while holding onto vehemently dedicated followings.

Sure, Phish is as hated as they are loved, but today, it’s nearly impossible to find anyone who loves Nickelback—or is even willing to admit liking the band in public.

In the case of genderqueer writer Khai Devon, it got them defriended on Facebook. As a joke, the blogger—who has opened up to friends in the past few years about their gender identity—posted a status “coming out” as a Nickelback fan; for Devon, it was about making “otherness visible.” The status read: “I may lose friends for this, and if I do, that’s okay. I have to be honest. I need to tell my truth. And the truth is, I like Nickelback.”

Whereas bands like Dave Matthews or Phish offer the solace of a cult for extant fans, liking Nickelback can be an isolating, lonely experience. Although bands like Insane Clown Posse might be objectively worse (for definitive proof, listen to “Miracles”), they tap into that very feeling of being marginalized or left out; hating ICP might only make their fans stronger. According to Devon, Nickelback offers no such comfort. It’s just music, not an experience.

Nickelback does not offer an understanding of the anger of youth disadvantaged in this society. Nickelback speaks instead to longing for love, to sex, and to other common factors. ICP has a cult following because it gives their followers a place to direct their anger, and a way to display it. It uses the most powerful of emotions, rage, and turns it into a tool of unity (and also encourages their followers to continue being full of rage and act out of that rage)… There’s no strong emotional element that unites Nickelback fans.

What’s fascinating, though, is how little people who dislike Nickelback actually know about the band. Devon often has their music on in the background while cleaning or hanging out with people, and friends who would otherwise performatively claim to “hate” the band often inquire about who this band is. Devoid of Nickelback’s cultural context, Devon’s friends find they kind of like it.

Could the same be true for me? If I really gave the band a chance, would I be converted into a Nickelback fan? For his 2007 book Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste, music critic Carl Wilson spent a year discovering his “inner Céline Dion fan,” on a mission to find out why we like what we like and why we hate what we hate. Is good and bad music really objective? If not, what does hating Céline Dion say about us? And what does hating Nickelback say about me?

My legacy as a Nickelback hater started in the mid-2000s. I’d never actively disliked them, and in fact, I tried really hard to get into them in high school, simply because it’s what all my friends were listening to.

But as a budding Anglophile obsessed with all things British, I found myself pulled toward The Smiths, Blur, Oasis, and U2. A friend once described taking acid as what it would be like to open the top of your head, consciousness without a ceiling. I felt that way the first time I listened to Viva Hate, and being a teenager and kind of an asshole, I decided to be really pretentious about it. It wasn’t just that I loved Morrissey; it’s that everyone had to know how much I loved him—and how much I did not love Chad Kroeger.

The final nail in the coffin for me came in 2006, when the band’s “Far Away” made it into a preview for the much-maligned seventh season of Gilmore Girls, a once critically beloved show that was on the decline after losing its showrunner and original network. This was a program defined by the things I loved most—laden with references to H.L. Mencken, Siouxsie and the Banshees, and The Godfather—and it felt like something was being taken away from me. The song was a sign an era had ended, more quickly than I was ready for.

But aside from these brief skirmishes, I have to admit that I knew little about the band, except that they’re from Canada and their lead singer sometimes plays rumpy-pumpy with Avril Lavigne. If I was going to hate them as much as I did—and eight years later, the answer was still a lot—my hatred might as well be informed.

In the past week, I’ve spent my days listening to every single Nickelback song ever recorded, even revisiting Chad Kroeger’s solo collaborations with Josey Scott (they recorded “Hero” together for the Spider-Man soundtrack) and Carlos Santana (who scored yet another top 10 hit with “Why Don’t You & I”).

Each of these two songs is a perfect illustration of Nickelback’s schizoid tendencies. As a band, they have two distinctive personalities. The first plays to the traditional Eddie Vedder Lite sound they built their brand on, best exemplified by their breakout hit “How You Remind Me.” Although it was written as a breakup song (and a glaringly nonsensical one at that), “How You Remind Me” became an accidental anthem for post-9/11 America, channeling our national anger and fear into generic post-grunge chord progressions.

“Hero” was not recorded with Kroeger’s band behind him, but it’s a perfect indication that Chad Kroeger was starting to understand the patriotic underpinnings of his band’s appeal. As America was selling out of red, white, and blue paint, Kroeger and Scott spoke to the country’s renewed sense of frontier individualism, also tapped by Toby Keith’s ubiquitous boot-rectum anthem. Accompanied by some requisite bald eagle imagery, Kroeger sings, “And they say that a hero can save us/I’m not gonna stand here and wait.”

Given that the band’s 2008 entry Dark Horse, which debuted just 13 days after Barack Obama was elected, was its first in almost a decade not to produce a top 20 hit, Nickelback’s fortunes appear tied to the Bush administration—their decline a sign of a changing tide. Although the national mood changed, their formula didn’t all that much; for instance, 2011’s Here and Now sounds remarkably similar to The State and Curb, the band’s first two albums.

Although the band has never been good, listening to their early LPs is actively difficult, simply because it’s so hard to tell the songs apart. Having listened to each of the aforementioned records twice, I couldn’t name one song from them, even with a gun to my head. Those records are less actual music than the idea of music—or rather, other people’s music. Like a helpful Netflix recommendation, The State basically tells listeners, “If you loved Pearl Jam, you’ll like the sound of these people learning how to play their instruments.”

Chad Kroeger might never be a great artist (to put it lightly), but over time, his band simply got better at stealing other people’s music, incorporating the mainstream rock trends of the era into a congealed gunge.

This brings us to the second Nickelback personality, which shares more in common with Céline Dion than one would initially suppose. In Wilson’s book, he argues that what makes Dion “uncool” is that she sings the kind of music that soccer moms listen to, and music fans often “avoid music that conjures up such listeners.” Wilson writes, “Or if you are a soccer mom, you may want to be the soccer mom who listens to Slayer, because you want to stay a little young and wild.”

It’s a truth of music that bands who stay popular on the radio for long periods of time become more mom-friendly as they age (see: U2’s All That You Can’t Leave Behind, Coldplay’s X&Y), and many of Nickelback’s later hits display that same tendency. To widen the band’s appeal, Kroeger made mom rock for moms who wouldn’t be caught dead listening to mom rock. This is the only explanation for how a power ballad as sappy, saccharine, and completely horrible as “Photograph” ever came to exist.

Although critics have derided “Someday” for its resemblance to “How You Remind Me,” the track shows the band dipping its toes into mom rock, taking their usual chord progressions and making them into an alternative prom anthem. By the time “Photograph” happened, Kroeger was drowning in a wide maternal sea, one that spawned hits like “If Today Was Your Last Day” and “Never Gonna Be Alone,” each of whose lyrics sound like they could be stitched onto a pillow.

In business terms, selling cleverly disguised soft rock marketed to the masses seemed like a smart move for the band. Chad Kroeger has always been open about the fact that his goal was to be as much of a corporate brand as a band, and these tracks earned Nickelback many of their biggest hits. “Photograph” was their highest-charting song since “How You Remind Me,” and “Someday” stuck around on the charts for almost a year. As Adele likewise found out, appealing to the mom crowd sells—and sells big.

But “Photograph” proves that success isn’t always a good thing if you’re selling subpar product, something movie studios know quite well. The worst thing that could have ever happened to M. Night Shyamalan’s The Village and The Last Airbender was their surprising box office success; despite being widely hated by audiences (eliciting many requests for refunds), each film grossed over $100 million in the U.S., utterly destroying their director’s reputation and career.

Although KnowYourMeme tracks the origins of Nickelback hate to an Urban Dictionary entry in 2004, “Photograph” (released in 2005) planted the seed that would eventually destroy Nickelback—music designed to appeal to everyone that ended up appealing to no one. And like the protagonists in Shyamalan’s The Happening, the band has been running from the changing winds of a cultural era ever since.

Like the sting of a cold breeze, Nickelback hatred continues to be both ubiquitous and amorphous, fitting into our viral era the same way that the band did during their Bush administration heyday, the decade of Paris Hilton and American Idol. Today, people claim to hate Nickelback because their music is unoriginal, or because they’re sellouts, or because they’re everything that’s wrong with the music industry, or because they just plain suck.

All of that is true. For over a decade, Nickelback made money off being a moldy Mr. Potato Head of American pop culture, but that’s not why we hate them. America hates them because the president might have changed, but we still need them to tell us who we are. Nickelback fans may never find their community, but their haters have.

Photo by Portal Focka/Flickr (CC BY N.D.-2.0)