Say what you will about Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia–and pundits and people on both the left and the right have been doing just that since his passing on Saturday–but when it comes to Internet freedom, he may have been one of the great legal minds of our time.

Let’s start with a 2005 case in which an Internet service provider named Brand X sued the National Cable & Telecommunications Association. The central issue was whether companies that promised high-speed Internet access had the right to use the faster infrastructure available to big content providers. To determine that, the court needed to first determine whether the Federal Communications Commission had the right to label cable broadband companies as providing an information service (which would mean they could deny them access) or a telecommunications service (which would mean they could not). Although the court ruled 6-3 in favor of the FCC’s right to do as they pleased, Scalia joined liberal judges Ruth Bader Ginsburg and David Souter in offering a powerful dissent.

“The relevant question is whether the individual components in a package being offered still possess sufficient identity to be described as separate objects of the offer, or whether they have been so changed by their combination with the other components that it is no longer reasonable to describe them in that way,” Scalia observed.

Although the FCC insisted that the product being offered by these Internet service providers (i.e., Internet service) was somehow distinguishable from their ability to provide it in a timely fashion (i.e., with high speed), Scalia argued that this distinction would be dismissed as self-evidently absurd when applied to other businesses. For instance, “If I call up a pizzeria and ask whether they offer delivery, both common sense and common ‘usage’… would prevent them from answering, ‘No, we do not offer deliver–but if you order a pizza from us, we’ll bake it for you and then bring it to your house.’” Indeed, “the myth that the pizzeria does not offer delivery becomes even more difficult to maintain when the pizzeria advertises quick delivery as one of its advantages over competitors. That, of course, is the case with cable broadband.”

Flash forward to last spring, when a federal appeals court ruled that NSA bulk data collection was illegal, paving the way for the case to head to the Supreme Court. According to the ruling by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, Section 215 of the U.S.A Patriot Act does not permit the government to engage in bulk collection of domestic calling records, even though the NSA had justified the practice by citing that provision of the bill. Because Section 215 “cannot bear the weight the government asks us to assign to it, and that it does not authorize the telephone metadata program,” the court declared, the program was illegal, adding that “if Congress chooses to authorize such a far-reaching and unprecedented program, it has every opportunity to do so, and to do so unambiguously.”

Although Scalia’s positions on Internet freedom ranged from supporting net neutrality to questioning whether a right to privacy exists throughout his career, the most important quality here is that they evolved.

Someone anticipating how Scalia would approach this issue may have assumed that he would side with the NSA, given his well-known skepticism on the notion of a government right to privacy. That said, an incident back in 2009 may have impacted Scalia’s view on this topic. A Fordham University law professor named Joel Reidenberg asked his class to search for any publicly available but personal information about Justice Scalia in response to a speech by the judge in which he questioned whether more privacy protections were really necessary.

By the time the dossier was presented to Scalia, it included the judge’s home address, phone number, favorite movies and foods, wife’s personal email address, and pictures of his grandchildren. “It is not a rare phenomenon that what is legal may also be quite irresponsible,” Scalia wrote in response to Reidenberg’s dossier. “That appears in the First Amendment context all the time. What can be said often should not be said. Prof. Reidenberg’s exercise is an example of perfectly legal, abominably poor judgment. Since he was not teaching a course in judgment, I presume he felt no responsibility to display any.”

While Scalia seemed resolute in his thinking at the time, though, it seems that the experience prompted him to at least question some of his initial conclusions.

When it came to two cases heard by the Supreme Court in 2014, in which the fundamental issue was whether Americans’ cell phones required as much protection as their private homes, Scalia acknowledged that law enforcement officers should be allowed to search phones in cases where the devices could obviously contain information relevant to a potential crime, he conceded that if someone is arrested for an offense like driving without a seat belt, “it seems absurd that they should be able to search that person’s iPhone.”

That same year, as the Supreme Court was confronted with the possibility of ruling on whether the NSA’s domestic surveillance program was constitutional (a case that Scalia felt was “truly stupid” for having reached his court, since he felt they were least qualified to make knowledgeable national security assessments), he was visibly impressed when an audience member at Brooklyn Law School asked whether data stored on computer drives could count as “effects” under the Fourth Amendment, which guarantees “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures.”

Although Scalia insisted that “conversations are quite different” from the four entities protected from unwarranted search and seizures by the Constitution, he implicitly acknowledged that data may fall into a different category altogether. “I better not answer that,” he told his questioner, since “that is something that may well come up [before the Supreme Court].”

Scalia was correct in observing that questions about where exactly the Internet falls into American jurisprudence are very tricky–and that the court will, eventually, need to render important decisions about them.

Although Scalia’s positions on Internet freedom ranged from supporting net neutrality to questioning whether a right to privacy exists throughout his career, the most important quality here is that they evolved.

Despite being a staunch originalist (meaning he believed cases should be decided based solely on the original intent of the Founding Fathers), Scalia recognized that the technological advances brought about by the Internet age meant that old legal traditions need to be re-evaluated in a new light.

Matthew Rozsa is a Ph.D. student in history at Lehigh University and a political columnist. His editorials have been published on Salon, the Good Men Project, Mic, and MSNBC. Follow him on Twitter @MatthewRozsa.

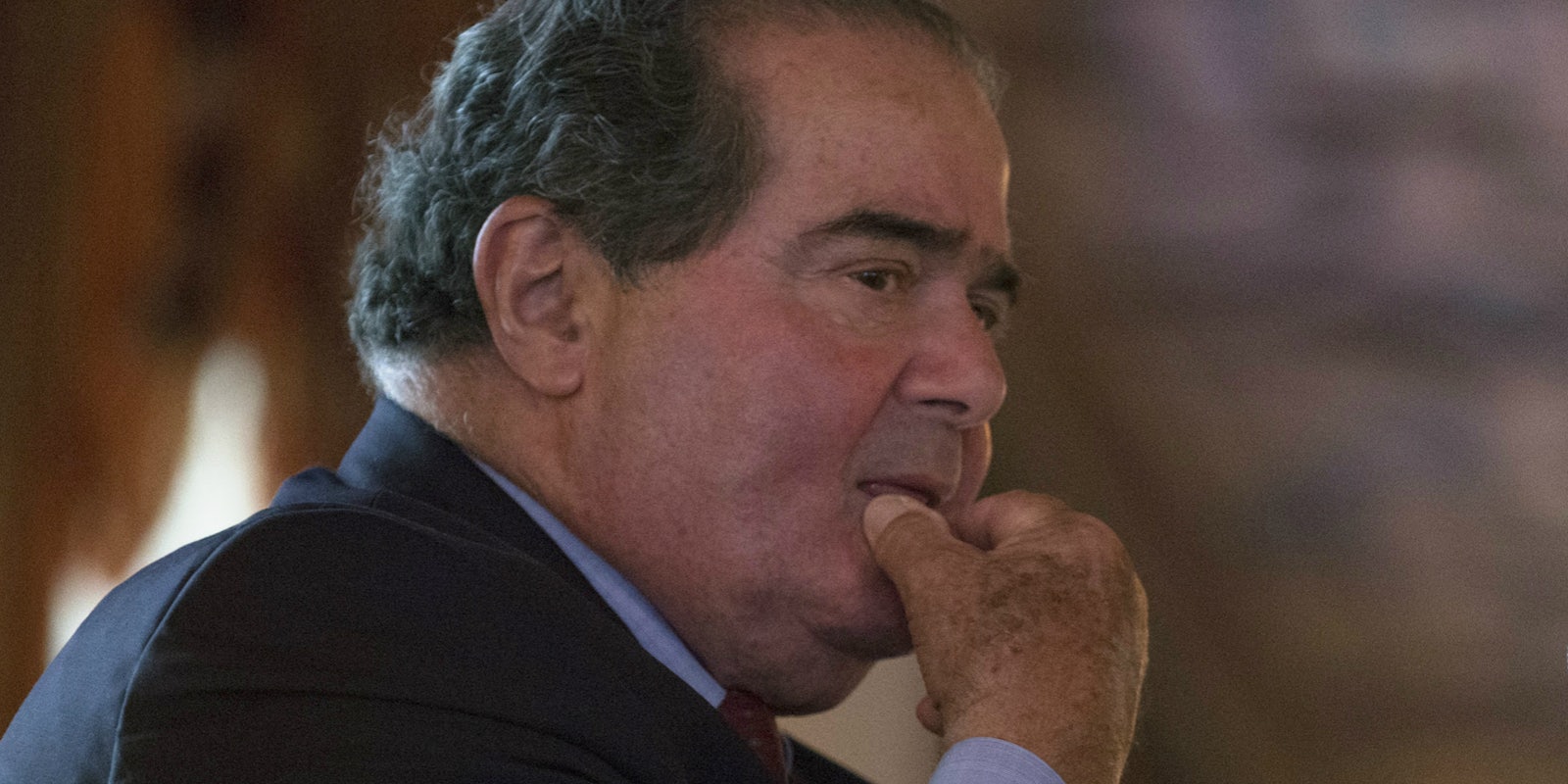

Photo via Levan Ramishvili/Flickr (Public Domain)