Recently, Blizzard announced its newest pet project, Overwatch. It’s got lots of awesome character designs varying across body types, races, genders, etc. Also, everyone seems to have their own personality, and that’s pretty rad! No more bland, faceless male protags here. It seems that Blizzard has finally gotten the message that inclusivity is actually really cool and important and fun to play around with when designing characters. It also—can you believe it—allows characters to be three-dimensional! And from a gameplay perspective, as Team Fortress 2 showed us, it’s paramount to be able to see a character and immediately recognize them as distinct from the rest of the cast.

Photo via SupercarGautier/Tumblr

But, there’s a few problems with these designs. While the men seem to have varied body types, all of the women seem to be rather cookie-cutter. As one commenter puts it, “These women are all palette swaps of each other.” They all still have the same proportions: Large chest, small waist, generally younger, with a fit figure and slender legs. Very, very few of these women have radically different body types, ages, physical features, or really anything that directly relates to their playstyle: For example, the sniper is in a form-fitting suit, but jumps around a ton? Wouldn’t that hurt? She should consider getting a form fitting suit that can also hold in the girls.

As a result, many of the women in Overwatch look and feel same-y. And that got me thinking, “What exactly can designers do to create variation in women characters?” Or perhaps a better question, “What can we collectively agree to avoid the next time we design our characters?”

What I want to discuss is the distinct lack of awareness in character design about body type, specifically for women characters in games.

To begin, I wanna talk about Pharah, the only woman in Overwatch with a remotely different build. She also has a half-hidden face. Nifty armor, a sweet shotgun-rifle hybrid, and a bird aesthetic. Cool stuff, huh?

So, here’s the first mistake. Even well-meaning, conscientious designers will fall into this particular trap at some point in their design careers.

1) A woman can have armor as long as the armor isn’t too bulky and can still show off her figure.

At first, many of you may be shaking your heads here. What? Freaking. Look at Pharah’s Arms! She’s built like a truck! But see, there’s the first problem. She’s not actually built like a truck: Her armor is. A lot of designers understand that women can’t just be in swimsuit-esque body morph suits. They have to have some strength or heft to them if they wanna look powerful. But of course, the figure must stay intact!

This happens so often that designers probably don’t even realize when they’re doing it. A perfect example is Vi from League of Legends. She’s supposed to look bulky, powerful, like she could tear through a bank vault easily. But she’s also supposed to look sexy because she’s a woman. Or something.

Same deal with Samus. She’s portrayed as a bounty hunter in full-body armor with lots of gadgets at her disposal, including a laser arm. She’s clearly powerful, but to what extent is that power only held in her suit? When she loses that suit, what does she become?

It should be relatively self-explanatory, but if it isn’t, in Metroid: Zero Mission, when Samus loses her power suit, she’s extremely susceptible to pretty much every little threat, including things you could kill in one shot when you had the armor. The swimsuit-style form suit doesn’t help that portrayal one bit, either.

When designing a strong female character, don’t be afraid to give them heft. And I don’t mean like arm heft. I mean like, body heft. Here’s two designs that I’d like to pick apart for a sec:

Photo via SketchChump/Tumblr

Here is a lady warrior. She is definitely strong, and is immediately noticeable as such. What stands out about her strength isn’t that her weapons or her armor make her strong, either. What makes her strong is her. She is strong. Not her power armor. Not her power fists. She is strong.

Photo via BookofRat/Tumblr

Once again, another design of a woman who is clearly strong as hell. This is Bowser re-imagined as a woman, which, in my opinion, stands out a lot more than our old Bowser. She’s confident, she’s menacing, and she can throw her weight around. And she’s clearly not afraid to display femininity, either! Oh, and check it out: Non-sexualized breasts that aren’t being hidden under clothing.

This is part of what I’m referring to when I ask how a woman is considered to be strong. Is it an inner strength, like confidence? Or is it outwardly displayed, like scars, weight, heft, body strength, large armor that is not solely used as a weapon? These are all questions the designer should be asking when designing a strong lady: Make her strong, not the circumstances of her presence.

2) A woman must still be able to be recognizably feminine, or people will not consider her a woman.

So, in the last point, it’s pretty clear that at first glance, most of those women portray some amount of femininity that makes them recognizable as women (even Samus has a small waistline and a noticeable chestplate). And, of course, it’s okay to have woman that show cleavage through armor as long as it isn’t sexualized, right?

Leona from League of Legends. Really confusing design: Supposed to be strong enough to carry a massive shield with one arm, but still has model-like proportions. But more importantly, she dons the infamous BOOB PLATE, with matching, SKIN-TIGHT WAIST ARMOR!

Alright, so here’s a few secrets that maybe we didn’t talk about much in school, because sex education isn’t a thing in the States (let’s be real here). First, not all women have breasts as big as our heads. Second, breasts don’t have to be immediately noticeable over clothing or armor. Third—and this one’s important—boobs are generally sensitive, and are not meant to be hit by things or knocked against shit in a fight.

For now, I’m gonna classify the armor that showcases a woman’s boobs front and center as sexual objects instead of something to be protected as boob platemail. So, y’see, if we had boob platemail for lady warriors in reality, that shit would hurt not only from getting hit by just about anything (nevermind a sword or a magic missile), but just by having our boobs knock against metal for hours, possibly days.

And, designers, think: What do most women use when they wanna go run or do sports that involve lots of movement? We use sports bras to keep boobs in and to make sure they don’t knock against shit. Sure, I’d be lying if I said having a fitted metal bra armor isn’t a really cool idea, but it’s not remotely practical.

So, to apply it to some real characters, let’s take a look at Overwatch’s Widowmaker, otherwise known as “why can’t I be her in real life.”

She’s got the trademark Portal heels that I assume are for movement/shock support when landing from high speeds. She’s also got this handy tool in her arm that allows her to grapple quickly onto any surface and swing away (thus, the boots). Also, she’s a sniper.

The slender suit makes sense in this regard, because she needs to be streamlined. What does not make sense is that her chest is being used solely as a sexual object. Every scenario I could think to justify that deep v-neck, no support bullshit made no sense.

A) She needs air because it gets hot in that suit. (This is the future and the suits are probably temperature controlled.)

B) The suit is form-fitting and wouldn’t be able to provide ample support. (Then why not just build in support or get rid of that stupid fucking deep V?)

C) I wanna see her boobs tho (That’s not good critical analysis.)

This happens more than I’d care to admit with character designs. Boobs aren’t treated as organs that can hurt or be hurt: They’re treated as pure, untouchable objects that are meant to be seen, to be glorified. This ignores the fact that, by their very nature, the more boobs can be seen, the more they aren’t being protected very well.

That’s what makes these designs so frustrating to see all the time: Not only are they not remotely practical, but even the characters themselves would find these outfits ridiculous. Leona is a strong fucking woman who can lift that massive shield and swing it at people; she’s not gonna care if her boobs aren’t showing under her armor. Widowmaker is a trained assassin that is so skilled at killing, she’s built her entire suit around that express purpose; so why isn’t she concerned about her boobs getting in the way when she’s trying to make a clean getaway?

While we think on that, here are some examples of women that don’t necessarily need to showcase their anatomy to be considered women:

Both of Impa’s forms in Skyward Sword do not cater towards modern conceptions of female-ness in order to satisfy the male-gaze. In this form, she is slender and flat because she’s meant to be swift, like a ninja. In her older form, she is slumped and cross-legged, like a wise shaman. In both designs, it’s apparent that Impa is a woman; but there aren’t any specific gendered cues to comprehend this. So why do we immediately jump to that conclusion?

Compare these with her older designs in Ocarina of Time, and we start to see some progress. (Also, what the hell is that Ocarina of Time design. She’s like, meant to be older but I think they still wanted to sexualize her? And they created this DeviantArt-like character that was trying to occupy both being old and wise and young and spry and it was just kinda confusing, I think.)

Although not discussed too often, it’s clear that Valve’s intent with the Pyro was to make a genderqueer character. That way, they could have the preconceived notion of perceived masculinity without the outward display of it. I put Pyro here to demonstrate how easy it is to blur the lines between definitively male and definitively female: baggy clothing.

While the Iron Tarkus armor from Dark Souls was made for a man, I want to show that the armor sets in Dark Souls were generally gender ambiguous, and were not catered towards men or women. In other words, when you put on Tarkus’ armor as a woman, it did not give you boob platemail, it gave you Tarkus’ fucking armor. The small differences in men’s armor versus women’s armor were so miniscule that they aren’t expressly noticeable at first sight, and that’s what’s brilliant about them. Your character is immediately recognizable as being decked out and cool-looking, not sexualized and vulnerable.

And really, here’s the heart of this issue: Why do we need to know what gender our characters are? Why is it a necessity to see sexualized female anatomy to understand, “Oh, it’s a girl character?” This also begs the question, “Why can’t we make more genderqueer characters? Why must they be male and female? And why does that have to be obvious?”

3) Women must be human/appear human.

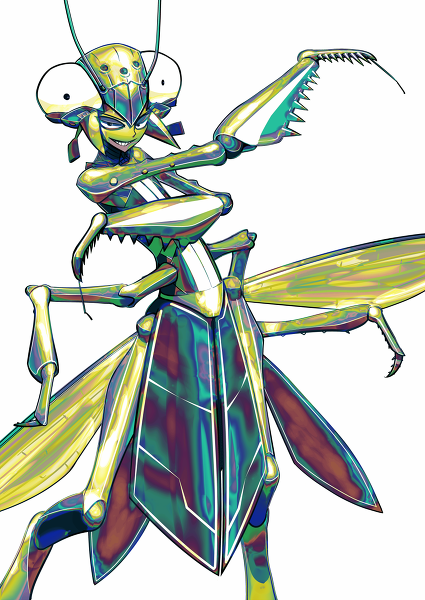

Why is it that when you’ve got a massive boss creature or a large beasty that you’ve gotta take down, they’re always, always, always gendered male? Why is it that in the absence of distinctly feminine characteristics, we subvert our own expectations by relying on some sense of implicit maleness? Why is it that when a monster isn’t explicitly a female, it must therefore be male?

Do monsters even have genders? Who are we to say that this demon or that beast considers themself “human male”? What I want to deconstruct here is the concept of monster genders and gender neutrality, and why both end up getting elided into maleness despite a designer’s intent. In other words, how can we as designers create monsters or creatures that are women that don’t need to outwardly display cleavage or curves?

In Overwatch, there’s a few characters I wanna touch upon:

Here’s Bastion. Bastion is a Gundam-esque robot that protects nature because it likes nature and thinks nature is pretty cool and safe. Also, it kills humans any time they come close to animals. Like, even remotely close. Did I mention this robot is a peace-keeper?

Despite using “it” pronouns for a sentient being and creating an ownership of this robot towards humanity (who owns Bastion? Is it the same humanity that Bastion actively despises? Or do we, as humans, own robots?), Bastion is actually a really cool gender neutral character. Bastion does not conform to humanity’s pre-conceived notions of gender, and does not inhabit male-ness or female-ness in any way. However…

This is Zenyatta. He is a omnic monk (read, robot monk) who strayed from his origins of dogmatic teaching and tried to connect better with humans in order to repair relations between humans and robots. Sweet, cool, great. But see, why is he considered a man here?

While Zenyatta still embodies some characterstics of maleness through his gendered clothing, who’s to say that his outward appearance reflects what he wants to see himself as? Who’s to say that Zenyatta must be a man? Does Zenyatta affirm masculinity because he wants to reconnect with humanity? Or does he do so because he wants humanity to connect with him?

In terms of design, that’s an important question to ask as a designer. Namely, why am I gendering this character male? Zenyatta’s face is covered. He exhibits gender neutrality through proxy of having a robot body that can be customized. Am I gendering this character male because he wants to be considered male? Or because there are no outward implications of female-ness that would otherwise construct her as a woman?

Lemme take a minute of your time to show you what characters could be women:

Photo via Pixiv/2635157

Screenshot via Gigantic

Charnok, from Gigantic. In game, he is gendered male.

This is also a lady.

Damn. Alucard from Castlevania Judgment has got it going on.

This is Vel’koz from League of Legends. Honestly? She can get it.

You see what I mean? Gender is constructed in such a way that even in the absence of a physically portrayed gender, we still lean towards maleness as designers. This is a shitty thing and we can collectively agree to stop doing it. Again, when designing a non-human character, ask: Does this character have a gender? Does this character want to be seen as a certain gender, and why? How? Show this. Don’t make us infer it through layers of bullshit backstory that you hid in development from your supervisors. Give it to us.

So, to summarize:

We put our perceptions of gender on our designs of characters before the pen hits the paper, before the brain has concocted a vision of them, before they even have a personality or a soul. Before we even understand that we’re doing it, we create gender for our characters. Now only that, but we feel we must outwardly show this decision through sexualization, instead of physicality.

We, as designers, do this every day to every character we ever make. Even when we think we aren’t doing it, we still do it.

So, let’s stop the bullshit. Let’s create characters that can speak for themselves. Let’s make physicality work alongside our characters, not for a male-gaze agenda or some notions of “people just won’t understand.”

Let’s stop using boobs as vessels for sexualization and treat them as physically part of someone’s body.

Let’s make strong women.

Let’s make monsters that are women.

And let’s spend a little more time thinking about all this between a character’s inception and their conceptualization. Otherwise, this will never change.

As for Overwatch, I guess I’ll play it. It looks like fun. Blizzard is clearly improving on its notions of representation; but at the moment, it’s all just the same Rob Liefeld-style bullshit we had before. You’re doing well, Blizz, but you can do better.

This post originally appeared on Medium and has been reprinted with permission.

Photo via Julian Mason/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)