Warning: This post contains spoilers for Star Wars: The Force Awakens.

The Force Awakens sound designer David Acord is a veteran of Star Wars films and TV shows, but even he got emotional when Han Solo stepped back onscreen for the first time in 30 years.

“The first time they come onscreen, the ‘Chewie, we’re home’ line—it gives me chills just thinking about it,” Acord told the Daily Dot. “That’s fantastic. I can’t get enough of that.”

Acord did sound work on Attack of the Clones and Revenge of the Sith before joining the production teams for the animated series Star Wars: The Clone Wars and Star Wars Rebels. He and supervising sound editor Matthew Wood, a fellow Star Wars veteran, are nominated for the Academy Award for Best Sound Editing at the 88th Academy Awards on Feb. 28.

In a phone interview from his office at Lucasfilm’s San Francisco campus, Acord revealed the secret animal sound behind dark-side villain Kylo Ren‘s “Force rumble,” explained the process of creating The Force Awakens‘s background chatter, and described the painstaking work that went into the sound design for key scenes like Kylo’s interrogation of Rey and the Millennium Falcon‘s escape from TIE fighters.

People are probably more familiar with the visual effects of The Force Awakens than the sound design. Talk a little bit about the challenges of your work and what you think some of your specific choices brought to the final product.

The goal, when you’re talking sound design with Episode VII, is to make it sit acoustically, with IV, V, and VI. That’s been J.J.’s goal all along with this movie: It was to feel like a true successor movie to IV, V, and VI, in terms of the tone of the movie, obviously the music, the sets, the practical effects, the puppetry, all that stuff. It’s supposed to have that same sort of vibe—but updated, of course; a 21st-century version of that. Sound-wise, that was the same goal. We wanted to honor the legacy sound effects that Ben Burtt created for the original movies but give them an updated 21st-century patina. That’s the challenge and the goal: to not only use Ben’s sound effects but give them an updated feel.

And the new sound effects you create have to sound like they live in that same environment, that acoustic world, that Ben has created. You have to create sounds that can feel comfortable in that world.

Do you think any specific choices you made really enhanced the final product in a particular way?

I like Kylo Ren’s sword, his new [lightsaber]. The moment it turns on and he flourishes it for the first time, it feels like a Star Wars lightsaber to me. It’s got that same vibe to it. But it’s not like any other lightsaber we’ve ever heard. But it doesn’t stand out so much that it’s [like], ‘Is that actually a lightsaber?’

Well, it does seem like a natural evolution of a lightsaber without being exactly the same thing.

Well, because Kylo’s lightsaber is an extension of himself, really—like all the Jedi, [where] their lightsabers are extensions of themselves. He is this, for all intents and purposes, an untrained Jedi, or a partially trained Jedi, who’s got this massive but raw and unbridled power. The sound we wanted to give his sword was to echo that sentiment. The sword, it’s like a claymore, like a Scottish claymore. It’s a very long sword. It’s got these guards that stick out the sides. The claymore’s a big, brutal weapon, and that’s kind of the way Kylo’s sword is. And it’s got a very jagged, rough sound to it; it’s a very raw sound. And the flourishes, it just sounds like this thing is going to come unhinged. It just sounds really rough and raw to me.

How involved was J.J. Abrams in the sound design process?

Here’s something that, maybe, a lot of people don’t know about J.J. He’s a musician, and a good one. He knows sound. He’s got an ear for it, and he’s interested in it. He’s very aware of it, right down to the smallest details. J.J. can give you notes on foley. He’s very in tune with his soundtrack—which is great, because he can give you specific details about what he wants, but he’s also an artist [and] he knows to let you have a crack at it in whatever way you want. And then, you know, you can narrow things down from there.

He is very in tune with what we’re doing sound-wise and will often give specific notes about what to do.

You’ve worked on the prequels and the animated shows The Clone Wars and Star Wars Rebels. What do you think you brought from those projects to The Force Awakens?

Well, [The] Clone Wars felt like six years of Star Wars boot camp [laughs] to get ready for this movie, in hindsight. Learning Ben’s [sound] library, which was paramount, first of all—[The] Clone Wars helped with that, the prequels helped with that—learning what all the different sounds were in his library, and also trying to learn his process for creating these sounds helps me create new sounds to live in that world.

On the pure editorial side of things, something like cutting a lightsaber fight—I’ve cut dozens of lightsaber fights and duels in The Clone Wars. Learning by trial and error over time, you kind of figure out what works and what doesn’t work. And for the movie, I have a bit of a head start in that world, as far as what I think is going to sound good, what isn’t going to sound good, what’s going to sound like a sword fight from IV, V, and VI, or what’s going to sound like the sword fights from the prequels. Because they have a different sound to them, those sword fights. And they’re staged differently, too, so it’s kind of appropriate that they’re cut differently.

One of the stars of every Star Wars film so far has been John Williams’s music. How do you make sure that your work mixes and merges well with his score?

We generally will work with a temp music track, which will be similar in tone to what the ultimate score will be. But it’s still temp, so you don’t get to really learn what John Williams’s track is going to be like until much later in the game. Not necessarily right in the final mix, but maybe shortly before that, you’ll start seeing tracks filter in.

The trick is to not cut sound effects that are going to interfere with the music, as far as frequency ranges and that kind of thing. I don’t want to create a ship pass-by that has too tonal of a quality where it’s going to clash with the music. You gotta be aware of those things. It’s generally good to avoid tonal sound effects for the most part, unless it’s going to really serve a specific purpose. Well, that’s actually not entirely true. Anyway, [cutting without final music] is a tough part, and a lot of that falls on the mixers to find the balance between effects and music—and dialog, for that matter—to decide what is a music and what is a sound-effects moment, [based on] which one is going to serve the story better.

How much did the sound design process for this film resemble the work on A New Hope? Did you go out there and record random sounds like Ben Burtt did in 1976 and then come back and see what you could make with them? Did you work solely with an existing library or do any field recording?

It’s a little bit of both, of course. We’ve got quite a library built of a lot of effects already. Star Wars is a franchise that’s been around for close to 40 years, so we’ve got a lot of effects already. But yes, there’s a lot of new things. I’d mentioned Kylo’s saber; that’s the sort of thing that we’d have to go create from scratch. New Force effects, Kylo’s ship—there’s a lot of things that we want to not go back to the well for. We want to create something new, something exciting, and, of course, there’s that challenge of making sure that it can live in that Star Wars universe.

Are there any interesting sound effects that you made from real-world sounds?

Just as a personal thing for me, I like that Kylo Ren’s Force rumble—he’s got this sort of chunky, almost animalistic Force rumble that he does when he’s interrogating and that kind of thing. And it’s sourced from my cat’s purr. It’s pitched and kind of slowed down, and it’s got a ton of low-end added to it. But you listen to it, it’s one of those things…it’s tough when you sort of pull back the curtain for sound effects, because then that’s all you’ll hear, is that. [laughs] But yeah, that’s Pork Chop purring.

Tell me about working on Rey’s flashback sequence. I know Ewan McGregor came in to record some dialog dialog for that. What did you want the sound design in that scene to accomplish?

A lot of hands were in on that flashback scene. That wasn’t just me. There was a lot of people. There [were] a lot of voices that kind of echoed through that scene, and that was an early Ben Burtt design idea. I think it was a joint idea between Ben and J.J. to have these voices echo. And later, that evolved into recording some new dialog. Because originally, it was lines from the old movie, and a lot of it was alternate, outtake lines…or alternate takes from the lines. So it wasn’t quite the same as the line in the movie. There was things like that that were wafting through there.

The idea was that it was supposed to be scary. J.J. wanted it to be somewhat nightmarish for her, [and] to scare the audience, for sure. And it’s also supposed to impart some information, as well.

[As far as] J.J.’s specific notes for that scene, all I remember were the notes about the bits of dialog floating through there. I’m sorry, I can’t remember anything else. That was one of those scenes that…was kind of worked on very early on and I don’t have a lot of information about that one. I didn’t do a whole lot on that scene on a personal level; that was more of a [sound designer] Gary Rydstrom thing.

We’ve mentioned Ben Burtt a few times. Some fans may not know what he’s contributed to Star Wars, but he’s responsible for some of the most iconic sounds in the saga. Can you talk about working under his leadership? What did he bring to the project that you felt really made a difference?

There’s two people that come to mind as far as the people that are considered the godfathers of sound design. One is Walter Murch and the other one is Ben Burtt. And they’re both…Northern California colleagues. Ben’s aesthetic for sound design—and I don’t want to speak for him too much—but it’s been an organic approach. It’s recording real-life sounds to be manipulated into something completely different.

The simplest example, which is the core of sound design, is crinkling tinfoil and tricking the audience into thinking that’s fire when you hear it. That’s a common one. That’s Ben’s thing. ‘It’s a gunshot, but an actual gunshot might not be that interesting, so how can we make this gunshot interesting? And so maybe if [there’s] a black-powder explosion on top of that gunshot—instead of just simply compressing the gun or making it louder, let’s give it a little extra something to make it not only bigger but [also] more interesting.’ I think that’s kind of Ben. That’s a very narrow example. You could go on and on and on about Ben’s design work.

One of the other great things in this movie is the abundance of background dialog. How much of that chatter is scripted and how much can voice actors ad-lib?

That’s a good question. A lot of that—the background PA [announcements] or [when] there’s two stormtroopers talking—that kind of stuff is what we would call a “loop group pass.” That would be something that we would do on the editorial side of things. We would direct “loop groupers”—and a lot of it’s ad-lib—to create dialog for background people. That’s generally what loop group is.

In this case, Matthew Wood was very careful to hire loop group people that were well-versed in Star Wars—people that have worked on [The] Clone Wars or Rebels or the prequels or anything like that. He wanted to hire people that knew that world [and] that could ad-lib in the language of that world. Some of those things were some very clever ad-libs by the actors, some of those things were written by Matt, and all of that stuff, of course, is vetted by J.J.

It did feel a lot like that scene in A New Hope with the stormtroopers idly chatting while Ben Kenobi sneaks past them. It had that spirit.

Yeah, yeah. Exactly. That was what they were going for. Again, harkening to the original trilogy and trying to make it feel—as much as possible, they wanted the stormtroopers’ conversations to have that same sort of mundane quality.

What were your favorite sound design elements to create?

Let’s see. There’s a scene in the movie where Ren is interrogating Rey as she’s shackled to the torture chair, and they end up having this sort of Force battle, basically, where at the end Rey has the upper hand and has basically entered Kylo’s mind and releases some of his darker thoughts. That was a fun moment for us. That’s a pure sound-design scene in the purest sense. If you’re a person standing in that room with them, you don’t hear those Force sounds. All the Force sounds are meant to be feelings; that’s not a literal thing. If you were standing there, you wouldn’t hear anything, except maybe the rattle of her chair. So that was a fun moment to play with that, to play with the back-and-forth, with the Force ebbing and flowing between the two of them, and there’s…music comes in about halfway into that scene, so there’s a bit of a dance you have to do as well with the music. I thought that was a really nicely done scene. I was really happy with the way that turned out.

It’s funny that you mention that, because that’s one of the things I was thinking about as an example of sound design essentially being dialog. There is a moment during their tussle where something snaps and Rey gains the upper hand. That moment has very clear sound design. And I would imagine that it was very difficult to decide how to illustrate that using sound design, but for me, watching it, it sounds perfect.

Yeah, and that moment…the sound design kind of plays like music, almost literally. Like you say, it plays like dialog. That’s actually interesting. I’ve never heard it put that way but it does…I always thought of it as playing like music, but I guess it’s a little bit of both. It is the language of that scene, the sound design. Yeah, that was a difficult scene and I think it was successful.

Maybe this is the same answer, but what sequence proved to be the biggest challenge for you?

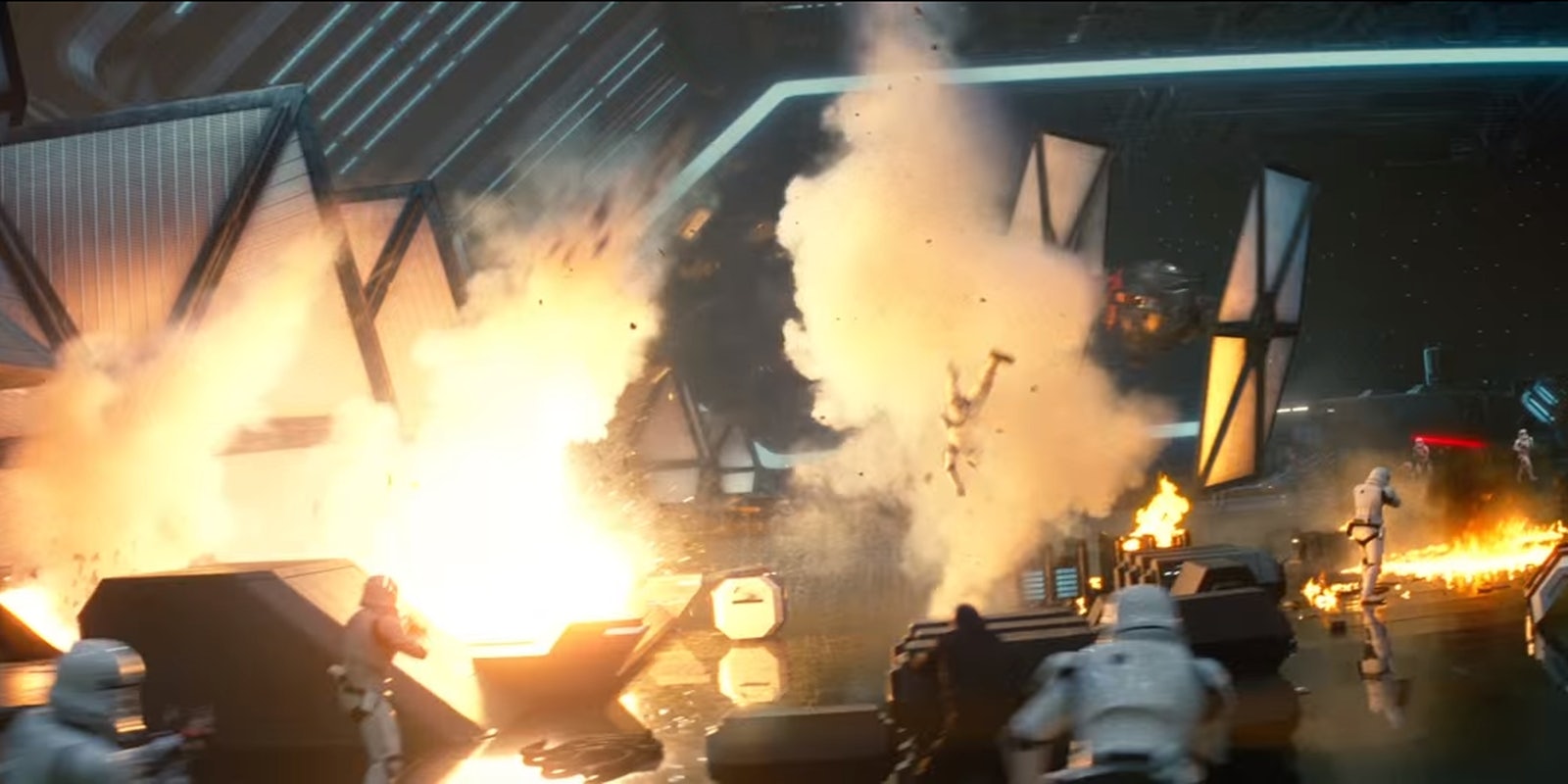

Well, that particular scene is at the top of that list for sure. But the Falcon chase in the Jakku junkyard, that was a scene that I spent a ton of time going over and over and over and cutting. It’s the biggest sort of space chase—not necessarily a dogfight, but space chase—in the movie, and it’s a nice, long, extended space chase. It’s the first time the Falcon’s flying. It’s a big, epic, quintessential Star Wars moment in the movie there. And so you’ve really got to bring it home on that [scene]. And you definitely are emptying out the bucket of Millennium Falcon sound effects and TIE fighter sound effects.

Ben was awesome enough to transfer all of his old original recordings of all these things. So we had fresh transfers of all these sound effects, and in the process [we were] discovering some new takes, new versions of the sound effects. So we got to use some of that stuff, and we created a few new things along the way. I updated the Falcon’s cannon, because J.J. wanted something that was nice and really punchy, so we kind of took a little bit of liberty with the Falcon’s cannon in that scene.

And then when it flies inside of the derelict Star Destroyer, that was kind of fun because then the sound can kind of completely change. You’ve just been flying and it’s just Falcon and TIE fighter and lasers, and then once they’re flying inside of it, you kind of give the audience a little something different to listen to even though it’s—the same thing’s happening, [but] the way we…this has a lot to do with what [re-recording mixer] Chris Scarabosio was doing at the mixing console. The way things are verbed and panned, the effects kind of change and then come back again as [the ships] exit [the wreck].

I think it’s a fun scene, and by the time they exit and they’re exiting the planet…you’re not exhausted. You’re excited by the end of that scene. And I love that part: it’s not overdone. God, that’s a weird thing to say. [laughs] It’s mixed so well, that scene, that I’m not exhausted by the end of it; I’m actually kind of invigorated by the end of that scene. I’m really proud of the way Chris Scarabosio mixed that.

You’re a Star Wars veteran at this point. But did anything in this film make you geek out even after all these years working on the franchise?

Yeah. I think the most obvious thing is seeing Han Solo and Chewie back. The first time they come onscreen, the “Chewie, we’re home” line—it gives me chills just thinking about it. That’s fantastic. I can’t get enough of that. It’s sad, of course—I’m sure people already know—it’s sad, of course, the way the movie turns out. But I think Harrison [Ford] was just phenomenal in that movie, and you’ve never missed a film character more than when he shows up onscreen and you just [are] like, ‘Oh my gosh, there he is, after all this time.’ That was the most exciting thing for me—to just see him onscreen and work on a movie with him onscreen playing Han Solo. That was a lot of fun.

Are there any fun Easter Eggs in the sound editing that people should listen for?

There’s some great voice stuff. I think Matt Wood just posted a thing on StarWars.com called “the vocal map” [of miscellaneous voice performances]. It was the loop group we were talking about earlier. Some of it’s loop group; some of it’s vocal sound design, pointing out who did what voices in the movie.

I think it’s fun that [Radiohead producer] Nigel Godrich is the stormtrooper that Chewie shoots when they first enter Starkiller Base. I voiced this character Teedo, who’s the little guy in the armored elephant that captures BB-8. I’m a big fan of the [Philadelphia] Eagles, and I was slipping in player names as part of Teedo’s dialog. [laughs] So if you’re a Philadelphia fan, you might hear a couple players’ names slipped in there. And of course I put my wife’s name in there as well.

I was surprised, while reading Matt’s post, that [The Clone Wars and Rebels co-creator] Dave Filoni didn’t voice the Crimson Corsair, the smuggler with the red mask who agrees to help Finn flee the First Order. People kept saying that he reminded them of Dave’s favorite character from The Clone Wars, the bounty hunter Embo.

You know who that is…

Well, I’ve just pulled up the post to check. I’ve forgotten who it was.

Oh, it’s me.

Oh, alright, well there you go. You have a very Dave Filoni-like voice to some fans. But that’s good. I can finally say that I’ve talked to the Crimson Corsair. That’s fantastic.

And Matt voices [Quiggold, the Corsair’s right-hand man]. Matt wanted us, he and I, to have a scene together. So that was that.

Screengrab via Star Wars/YouTube