Rarely has a film so bad had so much source material behind it. Sitting at a porous 15 percent on Rotten Tomatoes, Slender Man may well be the worst major theatrical release of the year. And judging by the spurts of confused laughter in the movie theater this weekend, fans and critics are in lockstep on this one.

Sylvain White’s (Stomp the Yard) horror film debuted with a paltry $11.3 million at the box office, capping a strange journey that the internet urban legend took from web forums to real-life tragedy to the silver screen. It turns out that the same things that make the myth of Slender Man so attractive to the internet render the story unadaptable on film.

If you aren’t extremely online, you likely first heard of Slender Man in 2014, when two Wisconsin girls were charged with trying to kill a third, stabbing her repeatedly with a butcher knife. They claimed they were inspired by Slender Man. Though most adults first found about Slender Man as a result of this story, the uniquely internet-based urban legend goes back years earlier, not to some tragedy, but to an obscure web forum.

The New York Times’ Farhad Manjoo called Slender Man a “horror figure for the selfie age.” Instead of an urban legend spread through word of mouth and campfire tales, the story of Slender Man was popularized through message boards and social media posts. This is painful to watch on film: Slender Man spends lots of time showing the audience text from bootleg Wikipedia pages.

Slender Man was the result of a 2009 photoshop contest on the web forum Something Awful. The site is remembered as a shitposting pioneer: SA produced many of the stars of what is today known as Weird Twitter. In addition to immortal Twitter accounts like @fart and @dril, Something Awful also gave birth to Slender Man.

It’s not hard to see why the images of Slender Man, created for a “paranormal pictures” contest, stuck out from the pack: the eerily tall, slim, faceless figure is at once familiar and horrifying, the perfect combination for a campfire legend. Add in the foundational element of the myth, that he only targets children, and a viral legend was born.

From there, as things on the internet often do, Slender Man took on a life of its own. The original thread about Slender Man on Something Awful grew so large that it is now contained in a 194-page PDF. Crowdsourced fiction about Slender Man was written, DeviantArt depictions were drawn, “sightings” of the creature increased, and there was even a “Trender Man” parody meme. An internet monster was born.

This film is not the first live-action treatment Slender Man has received. Slender Man was the subject of a 2009 webseries, a 2012 low-budget Kickstarter feature, and a 2016 HBO documentary. Law and Order: SVU, Supernatural, and even My Little Pony have all tackled Slender Man.

A number of other violent crimes have been allegedly inspired by Slender Man, in addition to the Waukesha, Wisconsin, stabbing that made national headlines. This explosion in popularity strengthened Slender Man’s legend: It was everywhere, and the sheer volume of information on the creature made the legend seem older than it was.

Yet this meteoric rise has rendered Slender Man ridiculous. There is so much Slender Man content online that even hardcore fans can’t agree on what the monster can actually do. In some versions of the legend, he has tentacles or fantastically long arms. Sometimes, he causes memory loss or insomnia, and in other interpretations of the story, he brings on coughing fits dubbed “Slendersickness.”

In the film, Slender Man sometimes attacks victims in the woods, almost in the spirit of a pagan ritual. In other instances, he conducts his attacks through their smartphones and tablets. There are also times when he psychologically attacks in the mind, as Freddy Krueger once did.

This problem of competing source material predates the film. The girls who stabbed their friend in the name of Slender Man did so believing that human vessels could act on Slender Man’s behalf. This aspect of the legend didn’t even exist until years after Slender Man was first created.

The film Slender Man suffers greatly from the myth’s convoluted history. While most movie monsters have a clear set of rules that define them—werewolves are killed by silver bullets, vampires need to be invited inside—the rules here are a hopeless jumble.

It is tempting to the blame shoddy writing, but the sheer volume of “evidence” that makes Slender Man so terrifying online shares some of the blame for the terrible storytelling. A film that didn’t pay respect to the conspiracy theory-like field of Slender Man studies that exists on message boards wouldn’t be true to the Slender Man story. But, the massive, contradictory body of “evidence” around Slender Man renders the film incomprehensible.

Slender Man represents a new, complicated future of web-based urban legends. While the stories of Bloody Mary and the Vanishing Hitchhiker have clear mythology, developed over years, the Slender Man myth faces the same problems that web-based conspiracy theories like QAnon and Pizzagate do. Because the legend is crowdsourced on web forums, there is no clarity to the myth; it simultaneously has hundreds of authors. The body of contradictory mythology ultimately ruins the story it is meant to support.

Myths and legends used to be developed orally, and were passed down over generations. This, in part, is why there is a clear set of rules that define mythological and horrific creatures as varied as Bigfoot, sirens, and the Loch Ness monster. Today’s legends, spread at the speed of the internet, don’t have time to cement themselves in our subconscious before they grow too large to sustain.

Slender Man is often compared to the timeless story of, the Pied Piper of Hamelin because both figures target children. The story of the Pied Piper, however, dates back to 1300 and still endures. Simplicity has kept the Pied Piper alive: the piper came to town, got rid of the town’s rats with his enchanted pipe, and when the town wouldn’t pay him for his services, he got rid of the children. That’s it.

When Robert Browning published his Pied Piper of Hamelin in 1842, the story was already over 500 years old. Russell Banks’ 1991 novel The Sweet Hereafter and the subsequent 1997 film drew heavily on the myth. The startup company in Silicon Valley is called Pied Piper. The Pied Piper will outlive Slender Man and all of us.

The very thing that enabled the viral spread of Slender Man, the steady stream of doctored images, apocryphal stories, and posts, is ultimately the legend’s downfall: There is just too much information. Legends, urban or otherwise, persist because they are simple and vague enough to believe. No one has been able to capture a clear picture of Bigfoot. Anyone who has met Bloody Mary died. The Vanishing Hitchhiker, well, vanishes.

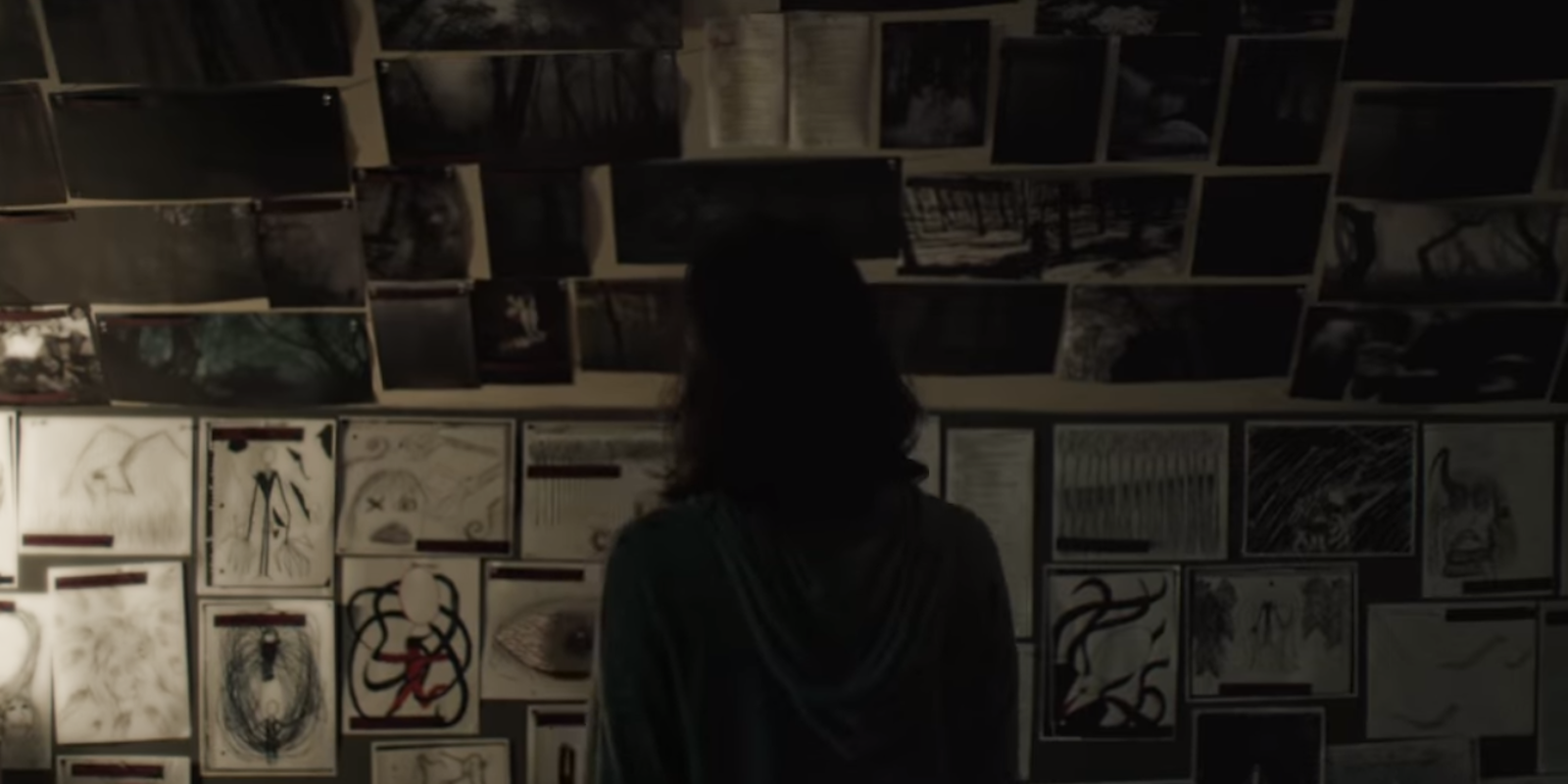

Slender Man’s terror is based on just how many images exist of the creature online. While this may be scary for a teenager clicking through post after post late at night, in the light of day, too much content kills the creature.

When the information surrounding Slender Man is viewed as a whole, the fear goes away. Slender Man stops being scary and starts being a perfect metaphor for the internet—disparate, vast, and so amoral that anyone can manipulate it for evil. Sure, that’s scary too, but you wouldn’t watch a movie about it.