In an industry drenched with toxic masculinity, Nick Robinson was a breath of fresh air. After early success working with podcaster Griffin McElroy, Robinson joined Vox’s gaming outlet Polygon in 2015, and he quickly became a fan-favorite for his quirky sense of humor. If something happened in games, Robinson wasn’t far behind with a woke joke.

Then, in August 2017, Robinson was accused of sexual harassment. After calling Overcooked’s Nintendo Switch port “shitty” and telling podcaster Landon VanBuskirk to “shut the fuck up,” accusations emerged that Robinson would approach women in games online and pester them to send nudes.

One woman said Robinson “used his influence” on her as a “random, barely legal fan” to convince her to send suggestive selfies, despite being eight years her senior. Another accuser, visual artist Elia Cat (who uses she/they pronouns), claimed Robinson “made [them] uncomfortable and hurt and anxious” and that he “treats women as sex objects.” Several alleged that Robinson preyed on their teenage friends. Polygon suspended Robinson as accusations proliferated before “parting ways” with him one week later.

After being let go, Robinson finally shared an apology. In it, he claimed “some of [his] advances were unwanted or handled poorly,” as if his aggressive nude solicitations were just misread cues while “flirting.” He even used the opportunity to humble brag about his following, and how he created “silly stuff” that “pulled [fans] out of a dark place.” The apology was not received well by his accusers or their supporters, who thought it seemed insincere.

“You didn’t mention how you’ve used your position to use women as sex objects then ghost them and offer half-assed apologies but whatever,” Cat said, quote-tweeting Robinson’s apology.

— Nick Robinson (@Babylonian) August 10, 2017

You didn’t mention how you’ve used your position to use women as sex objects then ghost them and offer half assed apologies but whatever https://t.co/mt9fEQv0tx

— Elia Cat (@psychedeliacat) August 10, 2017

When a person is accused of sexual harassment, they should ideally center the survivors’ voices and make conscious choices to stop hurting others. After Rick and Morty’s Dan Harmon was accused of sexually harassing Community writer Megan Ganz, for example, he openly admitted to his inappropriate behavior, showed a clear understanding of why it was wrong, and apologized profusely for his actions. Harmon used the moment as an opportunity to teach men not to act like him, and Ganz forgave him.

For someone like Robinson, who was not just a public figure but also a powerful one, that kind of response was more than warranted. But that response never came. After posting his controversial apology and then “taking a break” from social media for a few weeks, the accusations against him never came up again. By the end of August 2017, he was back creating viral tweets. To this day, he still pens jokes during events like E3’s annual press conferences and Apple’s Special Event keynotes. Either Robinson doesn’t understand how to apologize, or he’s purposely hoping the allegations slip into the past.

It even seems likely that Robinson is trying to hide his identity on Twitter. By December 2018, he changed his Twitter profile picture to a bizarre morph of Pikachu over his face. In May 2019, he also changed his display name from “Nick Robinson” to “Rusty’s Real Deal Baseball stan account.” As of June 2019, his account’s display name and profile pictures have changed yet again; he now uses a photo of Pappy Van Poodle from Rusty’s Real Deal Baseball under the display name “WE PAPPY FEW.” The only giveaway to Robinson’s identity is a tongue-in-cheek banner image at the top of his Twitter page that features his old profile, and his account’s username “@Babylonian,” which Robinson has used across his social media accounts for years. If one of his tweets finds its way onto your Twitter timeline, or if you’re lazily browsing his profile on your smartphone, it’s easy to miss that WE PAPPY FEW is actually Robinson.

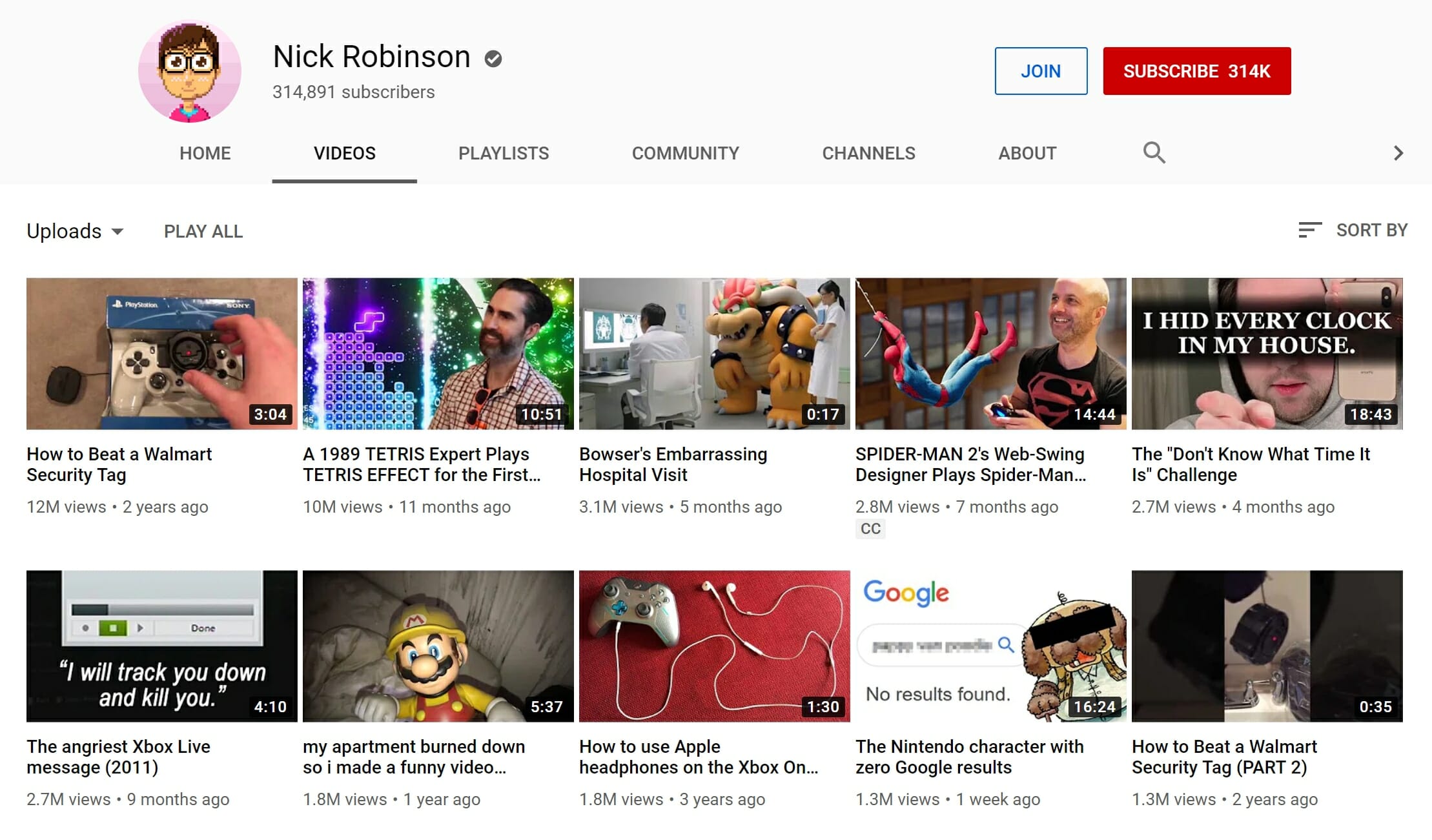

Robinson seems to be doing just fine on other websites, too. After a short break, Robinson went back to uploading videos on his YouTube channel in November 2017. His first upload since his departure scored over 73,000 views for a six-minute Super Mario Odyssey playthrough called “Mario’s Troubling Relationship With Death.” He now hosts over 130 patrons on his Patreon account, which may earn him anywhere between $223 to $1,000 per month, according to Graphtreon. Among his top 10 highest-viewed YouTube videos, seven were created after leaving Vox Media, including his second-most-popular video on Tetris Effect. That upload alone earned over 10 million views. Each of his top-10 uploads has over 1 million clicks.

Robinson may have lost his job over his behavior, but he hasn’t lost his career. He’s doing just fine in games. Whether his behavior has actually changed is another question altogether. But Robinson is just another example in a series of case studies that show how sexual harassment allegations do not inherently lead to the accused losing power. (The Daily Dot reached out to Robinson for comment but did not receive a response.)

READ MORE:

- A plain and simple guide to understanding consent

- The look of violent men

- What it’s like to work in the sex industry in the wake of #MeToo

- The importance of defining sexual harassment and sexual assault

While sexual abusers like Harvey Weinstein and Kevin Spacey have lost some of their power over the past two years, 2017’s Me Too movement never spawned an accountability process for outright ending abusers’ capability to cause harm. That means people accused of abuse can pen a half-hearted apology, slink away from the public eye for a bit, and then quickly restart their careers once no one is paying attention. This is true in games, too.

Writer and digital artist Liz Ryerson regularly discusses power dynamics and abuse in the queer community on Twitter. While she stresses she isn’t an expert on the topic, just an observer, she believes the games industry struggles with holding those accused of wrongdoing accountable for their behavior.

“I mean look what happened to most of the people accused via #MeToo in Hollywood. Their careers weren’t ruined either. Louis C.K. is still touring. Even Harvey Weinstein settled with his accusers, ” Ryerson told me over Twitter DM. “But no of course the game industry isn’t holding [those accused of abuse] accountable. There aren’t real structures to hold most people in power accountable in most of our society in general.”

In March 2018, the founder of LGBTQ gaming organization GaymerX, Matt Conn, stepped down after past and present company staff accused him of emotional abuse, sexual harassment, and employee mistreatment. One former unpaid intern claimed Conn repeatedly commented on his appearance, unsolicitedly went through his personal messages and photos, and exposed him to porn in the workplace. Another said Conn threatened them with legal action when they spoke out about their mistreatment.

Conn stepped away from public life briefly. Then he came back with a vengeance. In early March 2019, he called the allegations against him an “attack,” arguing he “took a whole year thinking about everything” but that “a lot of what happened was not in good faith.” He further threatened that “if you write something about me that is libelous or slander, I am now in a position to defend myself legally.” The message is clear: Criticize Conn, and face the consequences.

Matt? Way more than four people have spoken out against you, regardless of what you write in your new book. pic.twitter.com/HNOzAVfVyl

— Jennifer/Aster Unkle (@jbu3) March 9, 2019

Also, let’s be clear here: threatening legal action is absolutely a silencing tactic. pic.twitter.com/KkAo39IZ2d

— Jennifer/Aster Unkle (@jbu3) March 9, 2019

Like Robinson, Conn’s departure from GaymerX hasn’t necessarily damaged his career. He was credited as an adviser on Hidetaka “SWERY” Suehiro’s game The Missing, he claims he’s locked down a publisher for a book about his life, and he now serves as a producer on HumaNature Studios’ ToeJam and Earl: Back in the Groove. Coincidentally, Robinson even appeared on a May 2019 stream promoting ToeJam and Earl. The event was a reminder that accusing someone of predatory behavior won’t necessarily prevent them from returning to power.

“People risk their safety and their careers when they go public against men like this, but these men always have connections,” games journalist Jennifer Unkle tweeted after Robinson appeared. “They have people in their corner. And they’ll just slither their way back in, first chance they get, thanks to these connections. It’s so disheartening.” (The Daily Dot reached out to HumaNature Studios’ for comment from both the developer and Conn.)

Oh, hey, guess who showed up on the Toejam and Earl stream? Creepy pervert Nick Robinson! Guess birds of a feather flock together. pic.twitter.com/WyrSPILt78

— Jennifer/Aster Unkle (@jbu3) May 26, 2019

Real cool that abusive men in the gaming industry can just get together for live streams and parties with celebrities, even after they get outed as awful. pic.twitter.com/rF17Srv74t

— Jennifer/Aster Unkle (@jbu3) May 26, 2019

And here’s Matt Conn himself, appearing on the stream next to Toejam creator Greg Johnson. pic.twitter.com/MXeCB5Wz1x

— Jennifer/Aster Unkle (@jbu3) May 26, 2019

Conn and Robinson aren’t exceptions. In May, Webster University Games and Game Design student Tamsen Reed alleged the program enabled sexual harassment that she experienced from the program’s head, Joshua Yates. Reed claimed the university promoted Yates to an assistant professor position after she filed a formal complaint. Then there’s Riot Games’ Chief Operating Officer Scott Gelb, who remains with the company despite being accused of molesting employees and creating a hostile “fraternity mindset” that “disadvantaged women.” Gelb was only suspended without pay for two months, a relatively light slap on the wrist for such serious accusations. This is a pattern. If we want real, lasting change, we’re going to have to come up with ways to address the problem, not just discuss it.

Impact Justice’s Restorative Justice Director sujatha baliga criticizes the court of law’s use in punishing harm, as judicial systems simultaneously retraumatize the accuser while encouraging the accused to avoid telling the truth. Instead, she promotes restorative justice, which holds that all parties involved have the capability for growth and change. This plays out through a more communal approach where the accused admits to wrongdoing and shows signs that they understand the harm they imposed on others.

“Even without an admission of guilt from the person who harmed them, a survivor may still find some benefit from being able to say, face to face, ‘I don’t care if you deny it; I know you did this to me,’” baliga writes in an explainer for Vox.

Restorative justice is introspective. It treats harm as a communal experience that needs to be rectified beyond the two (or more) parties harmed. But it also begs the community, not just the immediate parties, to think harder about its most vulnerable and marginalized members.

Ryerson believes other people within the games industry should focus their energy on supporting those who need help to share their work or make ends meet. Granted, she isn’t an expert on restorative justice; she simply supports the idea’s application, particularly in the queer community. But her beliefs suggest something needs to change in how we approach abuse culturally.

“Not saying that you shouldn’t speak out about power abuses of course, not at all,” Ryerson said. “But people are at least well aware of Robinson or Conn now, so it’s not like there’s much else that can be done unless it’s by people who are working with them right now or something.”

Abuse in games isn’t just about a woke feminist ally or a queer games organizer. It’s about the systems that enable exploitation and abuse, and who benefits the most from their existence. If we want to take abuse in games seriously, we need to initiate the change we want to see. We each need to do the hard work that’s required, whether that’s listening to accusers, reflecting on and improving our own behavior, or supporting others when they need a helping hand.