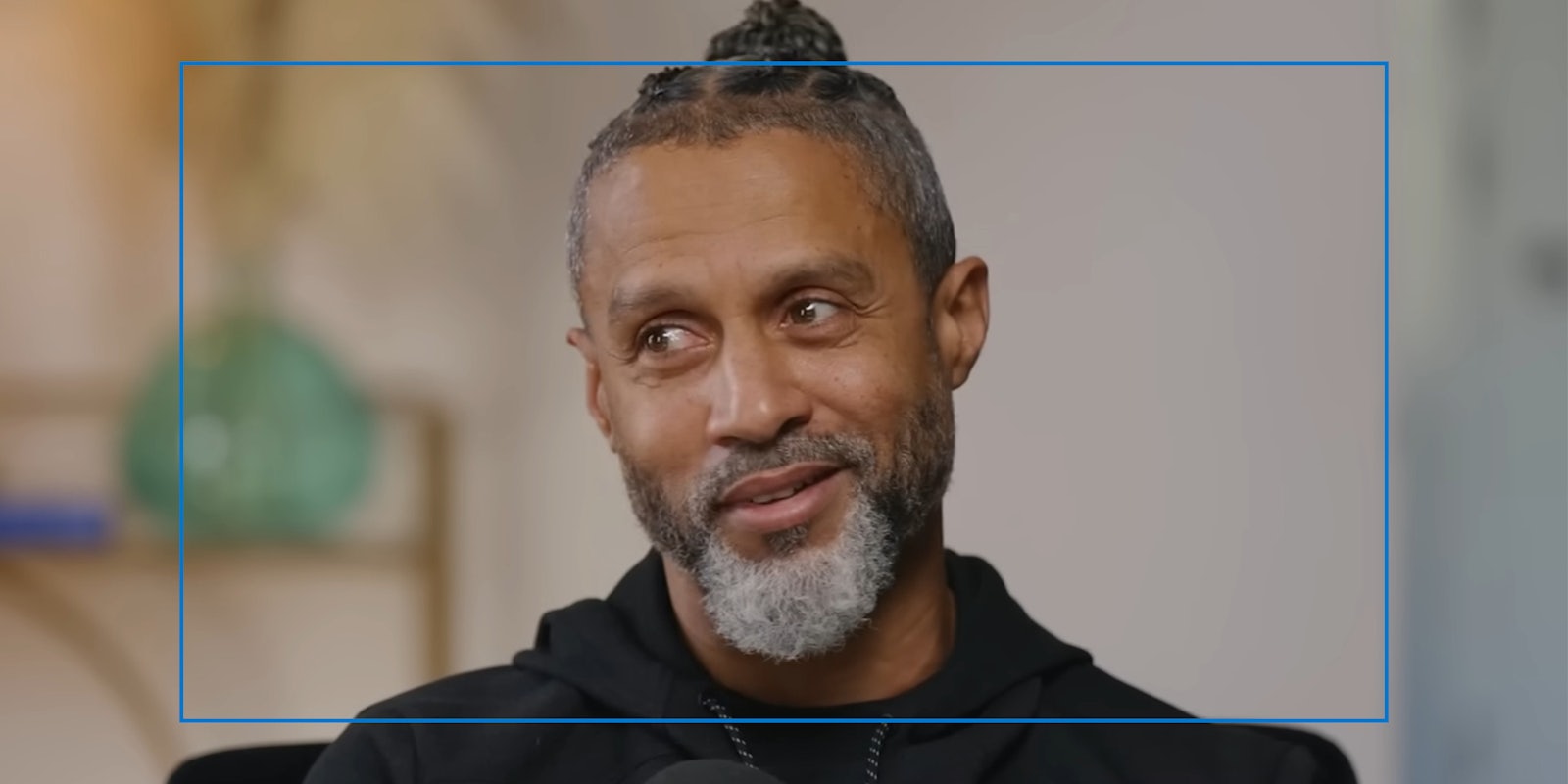

Before there was Colin Kaepernick, there was Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf.

That’s the premise of Showtime’s documentary Stand, about the former Denver Nuggets, Sacramento Kings and Vancouver Grizzlies player who originally came into the National Basketball Association as Chris Jackson—before his 1991 conversion to Islam and subsequent name change in 1993.

Stand, which went largely under the radar but enjoyed some critical acclaim, was released during Black History Month in February on Showtime. It covers a player who, from the late 1980s to the mid-1990s, was one of the most recognizable people in American basketball, selected 3rd overall in the 1990 NBA Draft, just one spot behind Hall of Famer Gary Payton.

Stand is a detailed depiction of Abdul-Rauf’s journey from a young teenager struggling with Tourette syndrome to being a promising young basketball talent, before going on to be involved in one of the sport’s most controversial episodes.

It covers his March 1996 suspension from the NBA, the penalty coming from taking a stance against refusing to stand for the National Anthem. His protest first began as a retreat to the locker room while the song played, and indeed, it was a few months before anyone noticed.

During a court-side television interview, he described the American flag as ‘‘a symbol of …tyranny… I think this country has a long history of that. If you look at history, I don’t think you can argue the facts.’’

This soundbite, which according to Stand was plucked from a longer commentary, provoked further debate, as some people considered his stance treachery while others were more sympathetic.

In the wake of the film’s release, some millennials and GenZers took to social media to show their dismay and bewilderment over Abdul-Rauf’s story—and immediately saw how closely related his story was to that of Colin Kaepernick.

Abdul-Rauf argued the U.S. flag and national anthem were symbols of the country’s longstanding history of racial oppression, informed by his then-new faith in Islam and extensive reading of political literature.

That wasn’t so far afield from the flack Kaepernick faced for his 2016 public protests — 20 years after Abdul-Rauf broke that ground.

‘Of course that caused the firestorm’

“Hey, this Mahmoud thing has really touched off some nerves,” said one caller on a Denver talk radio show hosted by veteran broadcaster Joe Williams, highlighted in the film. “I’m going to a game tonight, I hope when he’s introduced, everyone boos.”

In the documentary, Williams recalls that the media storm around Abdul Rauf’s actions came from his observations

“I noticed that Mahmoud was not standing for the national anthem,” he said remembering a game between Abdul-Raul’s Denver Nuggets against the Michael Jordan-led Chicago Bulls, “and I assumed everyone noticed that too. I remember the next day, I brought it up on air, no one had written about it and no one had talked about it. We brought it up and of course that caused the firestorm that you could imagine.”

The NBA would suspend Abdul-Raul on March 12, 1996, for one game, costing him $32,000 of his $2.6 million salary. They argued Abdul-Rauf had broken the rule requiring “players to line up in dignified posture for the anthem.”

A compromise was later reached, that allowed him to bow his head in silent prayer while standing during the anthem. But the protest became an indelible part of his story, much in the way it did for Kaepernick, though it didn’t sideline him in quite the same way. Abdul-Rauf would move to Sacramento after the ‘95-’96 season for two years, go to Fenerbahçe of the Turkish basketball league for two seasons, and then finish his pro career back in the NBA with the Vancouver Grizzlies.

While Kaepernick and Abdul-Rauf were both blacklisted, the outcome of their protests against the U.S. flag says more about how professional sports organizations respond to negative national media attention and the relationship the media has in shaping narratives on Black athlete protest traditions.

A compromise was later reached, that allowed him to bow his head in silent prayer while standing during the anthem. But the protest became an indelible part of his story, much in the way it did for Kaepernick, though it didn’t sideline him in quite the same way. Abdul-Rauf would move to Sacramento after the ‘95-’96 season for two years, move to Fenerbahçe of the Turkish basketball league for two seasons, and then finish his pro career back in the NBA with the Vancouver Grizzlies.

While Kaepernick and Abdul-Rauf were both blacklisted, the outcome of their protests against the U.S. flag says more about how professional sports organizations respond to negative national media attention and the relationship the media has in shaping narratives on Black athlete protest traditions.

‘There are symbols that represent a system’

Beyond the obvious comparisons, Abdul Rauf’s prayer salute, similar to Kaepernick’s kneel, opened up the debate on what it means to be an American patriot, particularly within public domains such as sports and entertainment.

It set the stage for competing narratives on the freedom of belief, speech, patriotism and race in a media spectacle not seen since Muhammad Ali refused his military draft obligations in 1967, or Tommie Smith and John Carlos’ Black Power salute during a medal ceremony at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City.

Director Jocelyn Rose Lyons, who made her debut with Stand, told Mike Muse on his YouTube interview show, “I am a very big advocate for leaning into the uncomfortable moments in the story. I feel that’s where the medicine is, it’s on the edges. Mahmoud’s story for me was one of courage, and how he faced those fires and transformed those into power.”

How American militarism is celebrated in public spaces, and how it’s shaped American identity from the Second World War on, is core to the discussion.

Sociologist Ivan Eland, in his essay, “Is Adulation of the Military really patriotic?” argued, “The US military and its opinion have acquired great prestige and are accorded hushed reverence in American society. The military and flag are worshipped as never before.”

This was an important point of contention for Abdul-Rauf, who explained in the documentary how his opposition to the U.S. flag was inspired by the likes of Noam Chomsky, who considers the concept of American exceptionalism, as he said in a 2010 interview, to be an essential yet destructive aspect of American foreign policy.

Abdul-Rauf remarks, “There are symbols that represent a system, and we (Muslims) only stand for Allah.” Today, a new wave of sports activism is allowing athletes to leverage their high-profile roles to become key influencers for social causes online, which benefits them, in the long run, should they find themselves blacklisted.

In the absence of social media, personal branding for celebrities was shaped by one’s ability to practice political quietism in the full gaze of the press and conform to prevailing attitudes on how Black people should best navigate professional or corporate spaces in post-civil rights and neo-liberal world.

Abdul-Rauf came of age during the late ‘80s and early ‘90s when political protest in sports ebbed to an all-time low. As Joseph N. Cooper explained in his article, “Race and Resistance: A Typology of African American sports activism,” the decline in African-American activism within and outside of sports reflected the idea that the gains of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, affirmative action policies, and increased access to white-owned capitalistic spaces had been fully realized.

This was precisely why Abdul Rauf’s stance was so controversial. “White American politicians can speak all day long about America’s wrongs,” he said. “But, as I quickly learned, if a Black athlete making millions of dollars claims that America is corrupt, the sky will come crashing down on his head.”

In this era, celebrities and influencers have more room to stand for the causes that are important to them, and we, the public now expect them to make use of it.

‘He should be applauded for taking that stand’

In a TikTok video liked nearly 17,000 times, Abdul-Rauf said, “If it wasn’t for those types of people, the Muhammad Alis the Malcolm Xs that led me to Islam, and then reading stories about the Prophet and when Allah says stand up for justice … ”

@yaqeeninstitute Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf reflects on being Muslim during his NBA career and how he incorporates Islam into his life. Link in bio! #nba #islam #fyp #explore ♬ original sound – Yaqeen Institute

For Abdul-Rauf, mainstream media used the controversy to push problematic narratives about Islam, race, freedom of speech and patriotism. Therefore, the controversy surrounding Abdul-Rauf must be seen in a broader historical context of how mainstream media has been considered a religion of dissent and “otherness” in the U.S.

Zareena Grewal, an American Studies professor at Yale University, argued in a journal article exploring the Abdul-Rauf suspension that immigrant Middle Eastern expressions of Islam were capitalized by some newspapers to portray Abdul-Rauf’s position and Islamic identity as anathema to American ideals and values. These were mischaracterizations that became more prominent in the American press in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks.

One example was a caricature by cartoonist Drew Litton from Rocky Mountain News. Here, Abdul Rauf is shown as a foreigner or Middle Eastern immigrant throwing the American flag into a dirty towel bin.

In other cases, other Muslims of immigrant backgrounds were used in news reports to disavow Abdul-Rauf’s conflation of religiosity and politics in his protest.

In a 1996 New York Times article, Hakeem Olajuwon, a Nigerian-American Muslim basketball player for Houston Rockets, at the time, suggested Abdul-Rauf was mistaken for using his religious convictions to be openly antagonistic against the American flag.

In another video report, depicted in the documentary, Olajuwon says, ‘‘In general, Islamic teachings require every Muslim to obey and respect the law of the countries they live in. You know that is—that is Islamic teachings. You know, to be a good Muslim is to be a good citizen.”’

This points to ways in which African-American Muslims and immigrant (Black) Muslims negotiate their patriotism in relation to the state, which may inform their perspectives on dissent. However, Zareena also suggests Olajuwon’s acknowledgment of Abdul-Rauf taking on a different and valid religious perspective from his own was not always included in media coverage.

Ed Fowler of the Houston Chronicle reported that Olajuwon said: ‘‘(If) Abdul-Rauf is certain his interpretation is the only acceptable one, he should be applauded for taking that stand at the cost of a magnificent livelihood.’’

As interest grows in the memoir and Abdul-Rauf’s documentary, and as appears on television networks and via YouTube and Instagram to speak about his experiences, we are reminded of the privilege of social media, particularly for issues pertaining to freedom of speech and conscience.

Abdul-Rauf was a casualty of his time for this reason alone. But his stance remains the same today, as it did then when he gave in an interview with the New York Times in 1996.

“I understand sometimes people view the flag as a sacred ceremony,” he said then. “People fought for this country under the banner … I just felt in my heart that if I can’t do something, and as a Muslim, we try to perfect whatever it is that we do … if I couldn’t stand, if I couldn’t do it 100 percent, I felt don’t do it at all.”

Adama Juldeh Munu is an award-winning producer at TRT World. In the past, she has written for Al-Jazeera, Refinery 29, The Huffington Post and Black Ballad. Her focus is on race, Black heritage and issues connecting Islam and the African diaspora. You can follow her on twitter @adamajmunu.