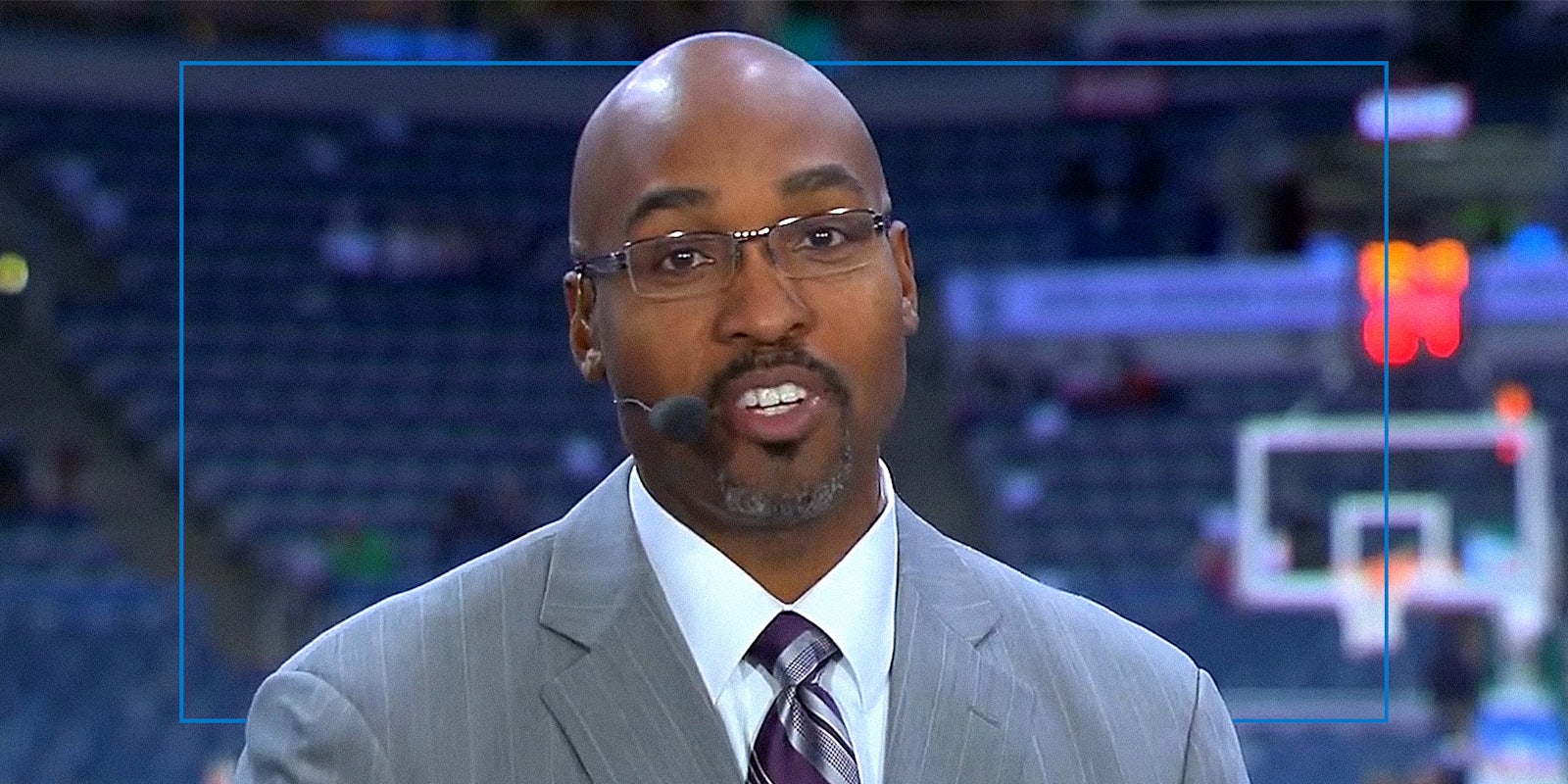

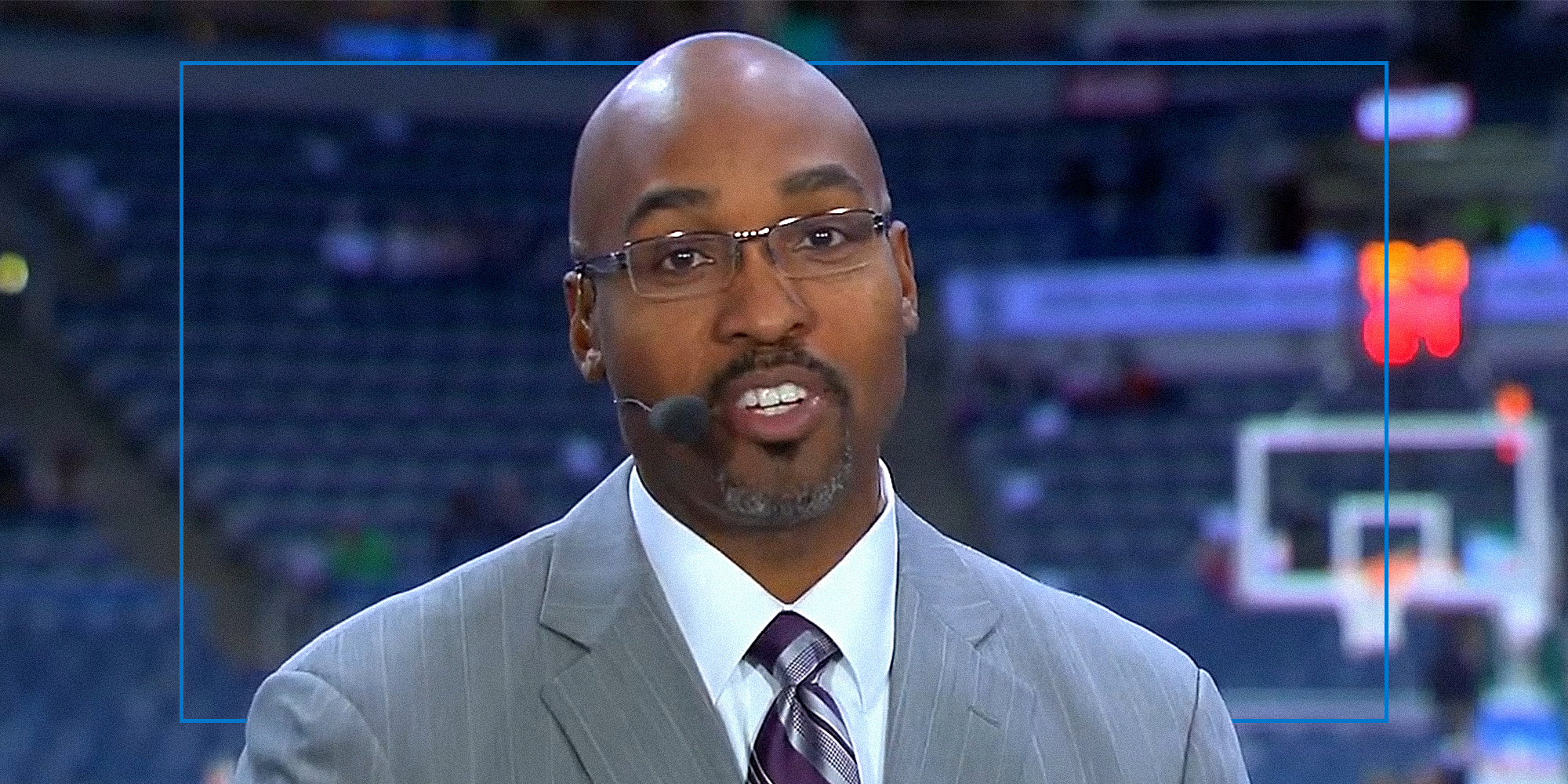

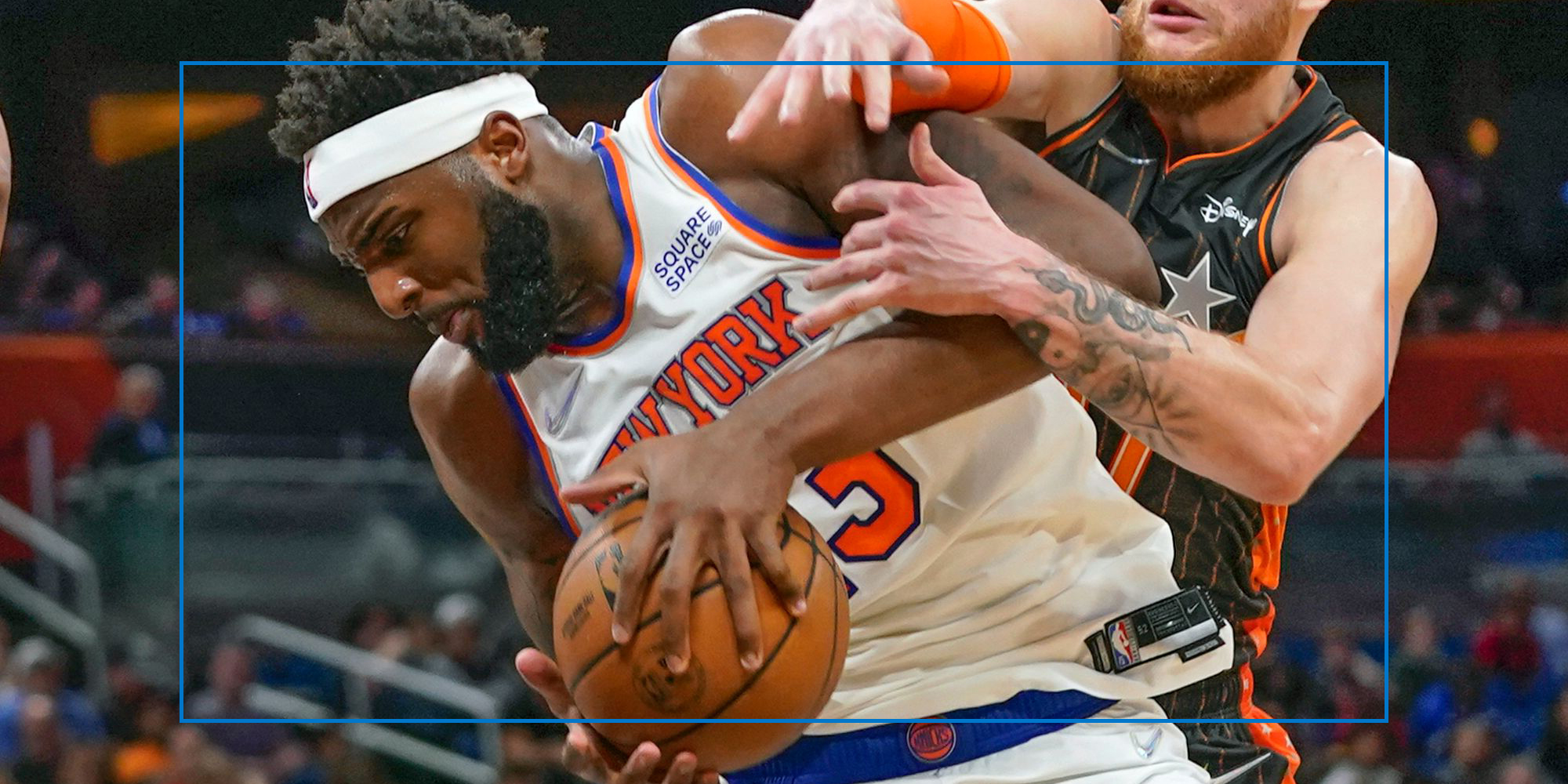

Leading into Tony Smith’s senior year playing basketball for Marquette University in 1989-90, then-incoming head coach Kevin O’Neill knew he had to center his rebuild of the program around the star player.

“I had a rule that nobody else could shoot the ball on any possession until Tony touched it three times,” the now-retired O’Neill says from his San Diego home. “If any other player asked why, I’d ask them: ‘If you were going into battle, would you want a sword or a spoon? Tony is a sword. You’re a spoon.’”

Smith delivered: He was responsible for almost half of that team’s points, assists and rebounds that season. After that, he enjoyed a 10-year NBA career highlighted by a six-year run with the Los Angeles Lakers. But after leaving American professional basketball and playing two years in Europe, it became clear to Smith his playing career had reached its end.

“In my case, it wasn’t so much that I had to come to a big decision,” Smith says. “It just became clear no one was calling to bring me in as a player.”

Thus began a new chapter of life without active participation in the sport in which he’d been involved with since grade school. To grapple with walking away from their beloved sport while facing an uncertain future can be a difficult transition for athletes to make.

“I didn’t have a plan for what I was going to do,” Smith explains. “I knew I was going to do something with my life. I just didn’t know what. The difference back then compared to now is players give more thought to what they’ll do next, and there are more opportunities in media or podcasts to stay in the public eye now.”

Chasing down opportunities on his own, Smith considered coaching and dabbled in NBA scouting. Still, nothing felt right. It was the decision to return to his hometown of Milwaukee and finish his degree at Marquette where Smith ultimately found direction. That led to a broadcasting career and successful sports talk radio gigs.

“I was fortunate to have the time to try some different things and work with different people,” Smith adds. “My personality allowed me to see what came along, but there are some guys who struggle when they can’t find their way soon after playing.”

Jaime Komer, Chief Transition Guide for the advisory firm Athlete Career Transition, insists some athletes need time to adjust to life after sports.

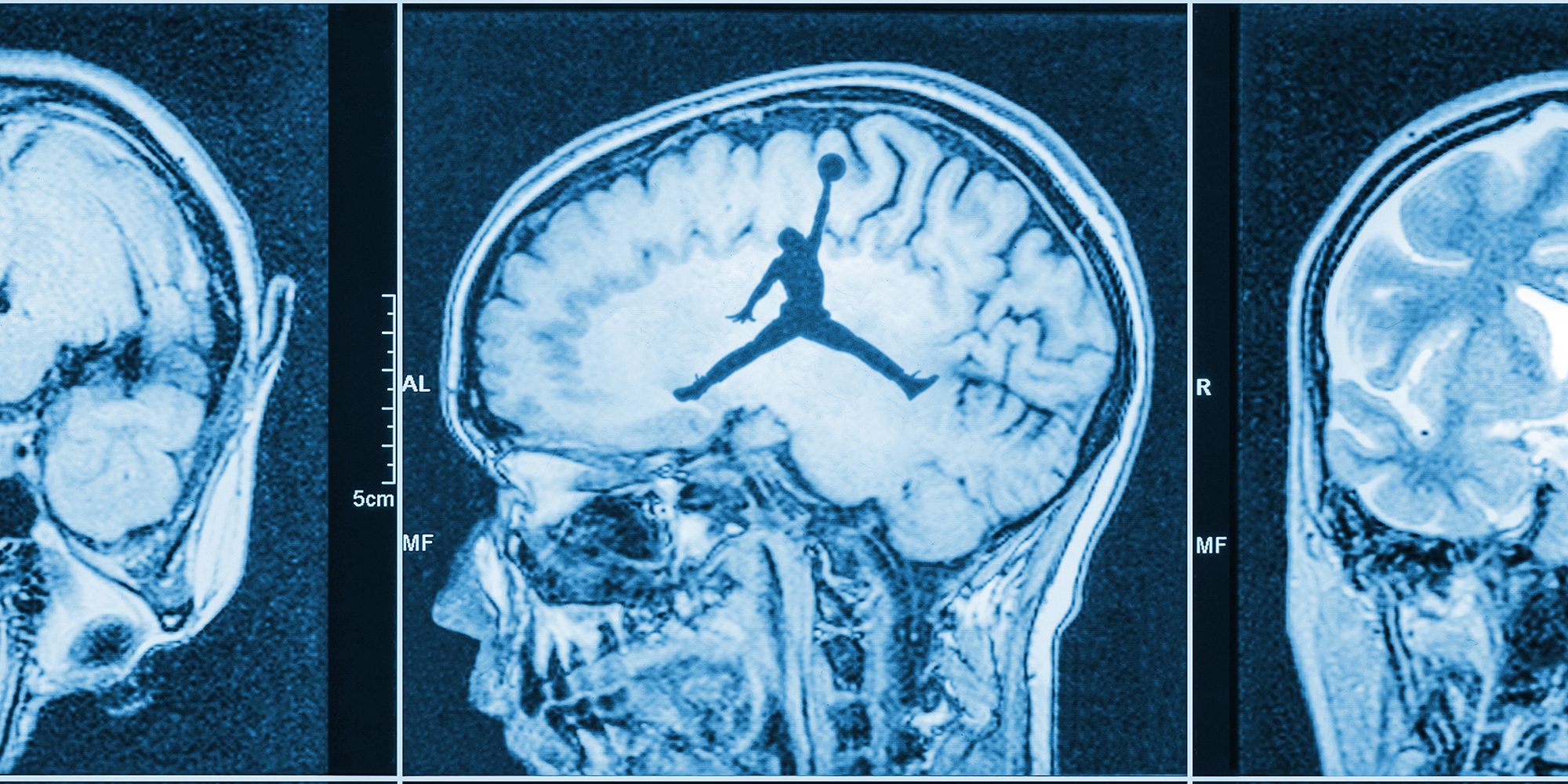

“As a pro athlete, you’re used to having a greater purpose you’re working toward that’s deeply connected with your identity,” Komer says. “One of the challenges is also one of the opportunities when retiring—the long term exploration into finding a greater purpose. This takes time and self-exploration.”

According to Komer, one of the biggest challenges for transitioning athletes can be assessing their relationship between identity and self-worth.

“As athletes, our identity, for the most part, has been based on what we do—our performances, wins and losses,” Komer explains. “With this focus on what we do versus who we are, we can find ourselves attaching our self-worth and identity to something outside of our control. If this isn’t a recipe for burnout, anxiety and chasing happiness, I don’t know what is.”

In her work, Komer encourages athletes to look to the long term as they have the opportunity to redefine their identities without dependence on external circumstances.

“This is what I call being a ‘human athlete,’” she adds. “It’s shifting your identity and self-worth from what you do to who you are.”

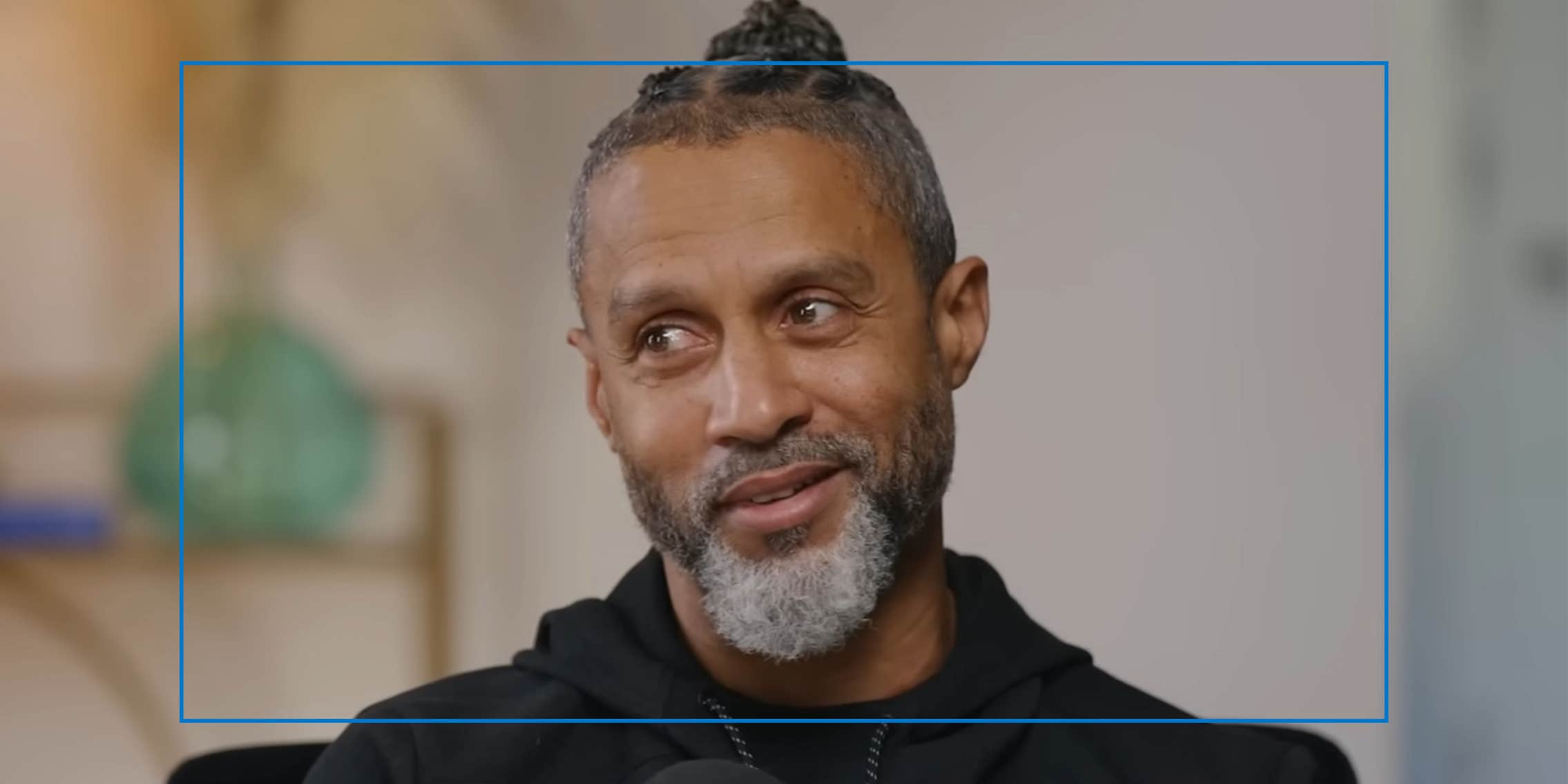

Lorenzo Alexander had a somewhat unusual career—he was drafted to the Carolina Panthers as an undrafted free agent out of Cal-Berkeley and spent 15 years in the NFL without any major injuries—yet still faced a similar challenge post-football. He says the struggle of retired professional athletes is often minimized due to their high earnings, but financial stability doesn’t make up for the loss of routine.

“Having the money doesn’t necessarily fill your day,” Alexander says. “The sport would fill most of the year. Now, there’s no practice to get you out of bed. You don’t have to lift. You have to get used to being around the kids. Your wife has to get used to having you around. You have to get used to not having those friends and teammates around you.”

By 2015, the former linebacker felt his NFL career was beginning to dwindle. A successful season extended his career for a fwew additional seasons, but Alexander eventually realized he was at peace walking away from the game and would make 2019 the end. At that point he was playing for the Buffalo Bills, and though they offered him another contract, Alexander opted to walk away.

“I had always been intentionally preparing for life after football,” he explains. “Being undrafted and on a couple of practice squads before discovering my niche was very humbling, and I felt my career could end at any moment. So playing 15 years was quite an accomplishment.”

Early on in his pivot from full-time athletics, Alexander prioritized developing order in his day so that he wouldn’t be overwhelmed by a sudden lack of structure. He swapped his team’s schedule for his phone’s calendar app so his days would always be planned out. That helped him immensely when it came to sorting through the excess of opportunities that presented themselves after retirement.

“Once I wasn’t playing, everyone wanted me to be a part of something,” he says. “I had to learn how to tell people no, and that took some time.”

Another hurdle the NFL veteran faced: After 15 years of tackling and fighting off blocks, he needed physical therapy, but lacked the priority access to team therapists he received while working in the league.

“Even though I no longer run through people for a living, the trauma and chronic pain is still there,” Alexander says. “Instead of addressing the problem the next day, I have to endure the pain and discomfort for days or weeks depending on availability.”

Alexander now maintains his own morning routine between visits to the chiropractor or physical therapist.

To help current players prepare for the issues Alexander encountered when he walked away from the game, he’s currently applying to serve young men on active NFL rosters through the Players Association.

“Unofficially, I had been doing that as a player rep and Players Association executive committee member, serving the men in my locker room by making them aware of the resources we have bargained for in collective bargaining agreements,” Alexander says. “This new opportunity will allow me to develop player leadership, improve player understanding of the business of football and inform them of challenges to be aware of in transition.”

See more stories from Presser – examining the intersection of race and sports online.