Southwest England is full of pastoral beauty – low, rolling hills, mesmerizing coastlines, and cliffs that rival the famed cliffs of Dover. Nestled in amongst these green valleys are countless little villages, each one with its own proud history stretching back thousands of years.

On cool autumn afternoons on the weekend, it wouldn’t be uncommon to see a drove of people in this part of the world filing into the pub to watch the Exeter Chiefs game.

And while you might expect the fans to be wearing a few Exeter shirts or the iconic white and red rose English jersey, you probably don’t expect a white man in a traditional Cherokee headdress. Or his children, chasing each other with inflatable tomahawks.

Yet, that seemingly incongruous image is one that’s been part and parcel of Chiefs support — and why some determined a change was needed, going online to bring England into an ongoing debate that some American franchises have grappled with in recent years.

Change agents

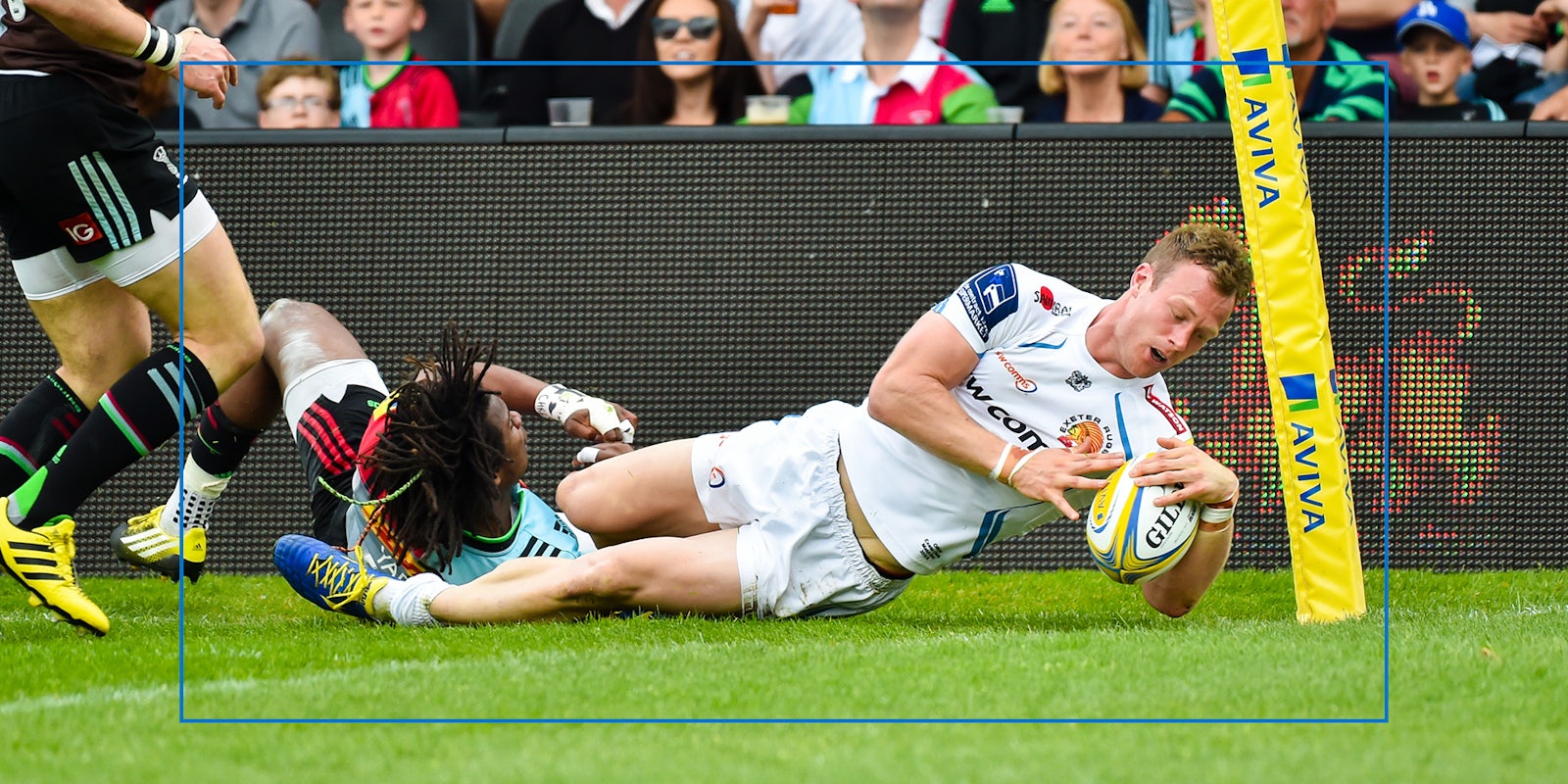

The Exeter Chiefs have come under fire in recent years, though not for their results.

Indeed, their teams are some of the most successful in England with their men’s team winning the Gallagher Premiership twice and crowned European champions in 2020, while their women’s team was league runners-up in 2022.

However, the Chiefs achieved all this success with overtly harmful and disingenuous branding featuring Native American imagery.

“It wasn’t just the logo that was the problem,” says Elizabeth Holloway, a lifelong Chiefs fan. “It was everything about their branding. Their store was the ‘Trading Post,’ they had bars called ‘the Wigwam,’ and this cartoonish mascot called ‘Big Chief.’”

Holloway and a few like-minded Chiefs fans wanted, in her words, “to be as proud of our team off the field as we were on it.” That feeling led to the launch of Exeter Chiefs for Change in 2020 — an online grassroots organization dedicated to eliminating Exeter’s racist branding and logo.

In just under two years, they were successful — at least in part.

In January 2022, the Exeter Chiefs announced that they were dropping Native American imagery in favor of Celtic Dumnonii imagery – a brand celebrating Devon’s local history.

This change wouldn’t have happened without the pressure online communities put on the club.

The roots of the Chiefs

The Exeter Rugby Club has played in Devon for over 150 years, making them one of England’s oldest teams. Storied though their history might be, it was not until rugby’s professional era in the late 1990s that the Chiefs were first christened.

According to Robert Kitson’s book, Exe Men, team owner Tony Rowe was at a loss as to what to call his team in the new era of professionalism until he was tipped off to an old Devon tradition of calling your starting 15 players the ‘chiefs.’ With a name in place, they commissioned an artist to create a logo, and the Exeter Chiefs were born.

After ascending to the Gallagher Premiership for the first time in 2010, people started taking notice of the team’s imagery and realized that it was problematic and perpetuating harmful ethnic stereotypes.

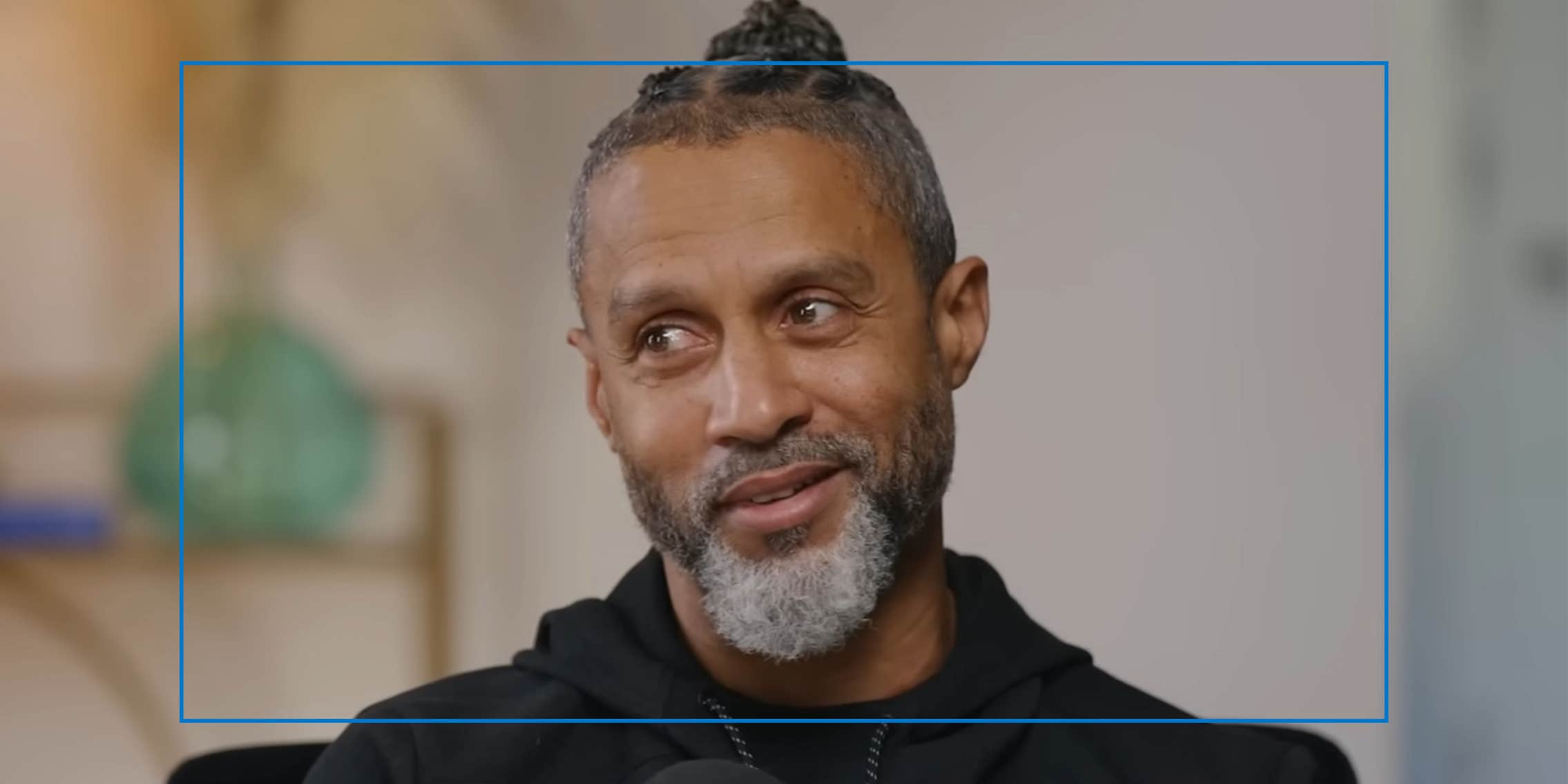

Rowe himself was at their first championship in 2017, appearing during post-match celebrations in Native American regalia, recalls Lee Calvert, co-host of the popular podcast Blood & Mud Rugby.

“That was actually one of the first Premiership games that was broadcast to the United States,” says Calvert. “It was a bit shocking, to be honest, to see him and a few others come out with headdresses on.”

“When I try to explain it to people here in the UK,” he says, “I tell them wearing a headdress is like wearing a British army uniform with medals that you never earned. People here are incensed by that, so why would they just accept it when Chiefs fans wear headdresses?”

Increasing online pressure

“When we started off, we never had a problem with the name ‘Chiefs,’” Holloway explains of Exeter Chiefs for Change’s mission. “This is a part of the country with a rich history of Celtic tribes and there was also a push to increase tourism to the area. We thought that a team that highlighted Devon’s identity would be a natural fit.”

But the Chiefs’ board of directors initially bristled at the notion of change.

“There was a board meeting,” Holloway recalls, “where we sent an information pack. We had research on the harm that imagery like this does, statements from Native American campaign groups, and even a local historian who had written about it a few years earlier.

“But at the board meeting, their only conclusion was that the mascot could be considered problematic, taking the ‘Not Your Mascot’ slogan literally and concluding that the rest of their branding was respectful.”

So, the ‘Big Chief’ mascot was removed, but the Exeter Chiefs for Change still had work to do.

They had grown a dedicated online Twitter following, created a petition gaining thousands of signatures, and were featured on several news sites and rugby podcasts, including Calvert’s Blood & Mud, helping to spread the word.

“We eventually approached the NCAI and brought this to their attention,” says Holloway, referring to the National Congress of American Indians.

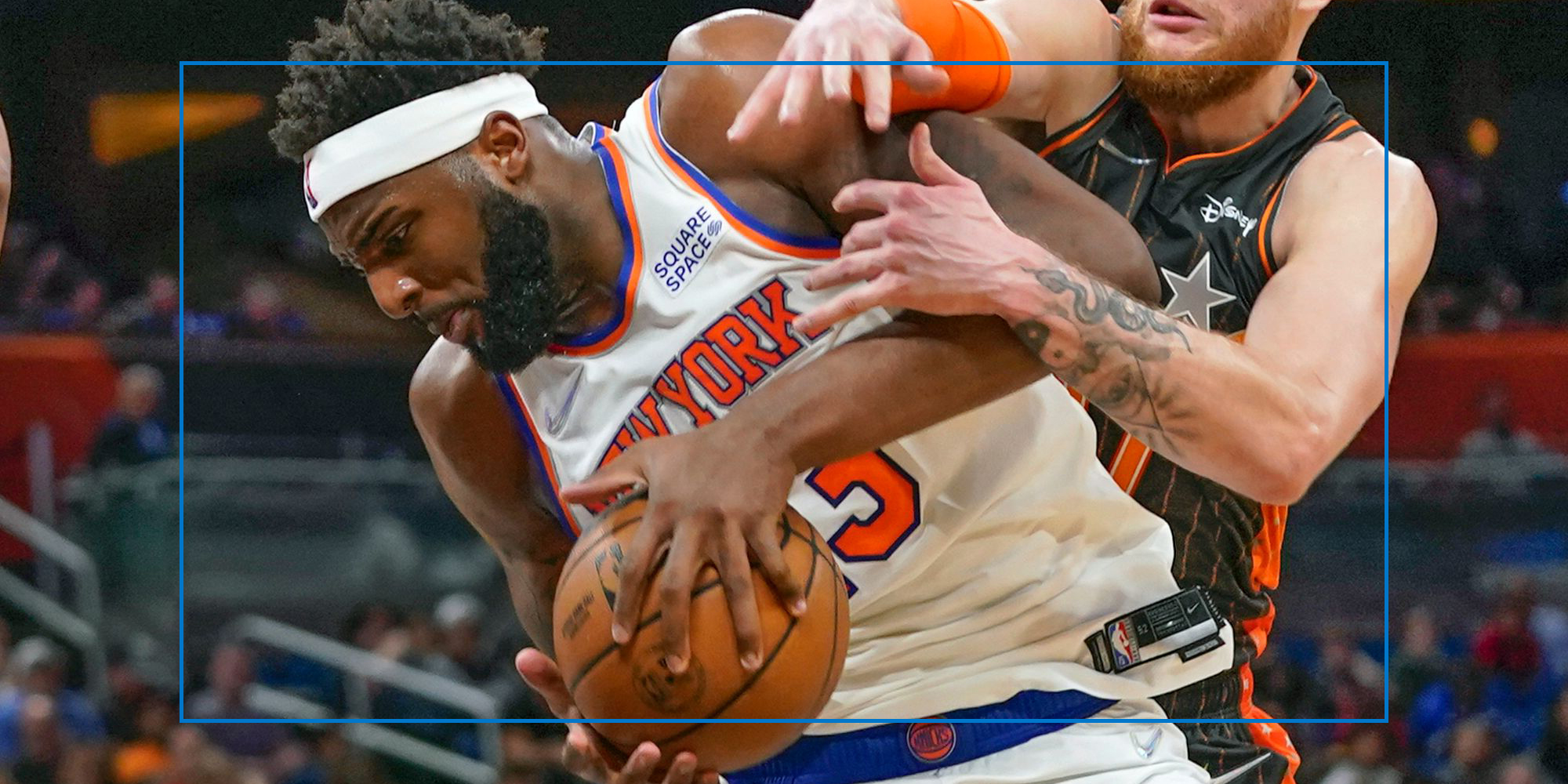

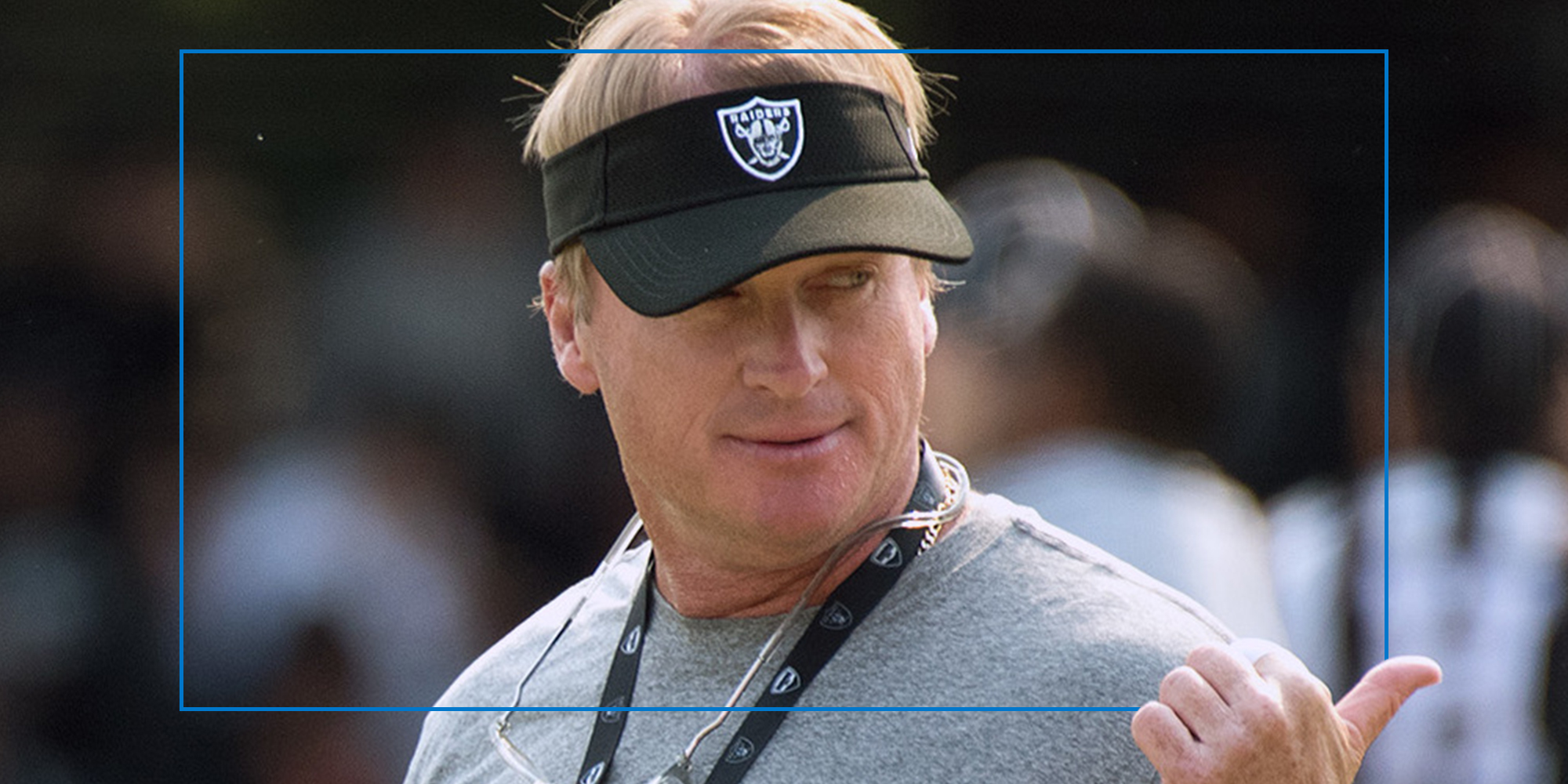

“We knew that they had already run campaigns to change the branding of American sports teams,” she recalls, including rebrands of both Major League Baseball’s Cleveland Guardians (the Indians for much of their century-plus tenure) and the National Football League’s Washington Commanders (even more problematically, dating back to the 1930s all the way to 2020, the Redskins).

“They wrote an open letter requesting the Exeter Chiefs change their branding to something that was not harmful to Native Americans and sent it to them before the next board meeting.”

The letter from the NCAI, along with mounting pressure from social media backlash led the board of directors of the Exeter Chiefs to finally make a decision: the brand redesign would be implemented in July 2022.

Not without hiccups

The shift hasn’t been without its hiccups. While the old logo has been removed, the Tomahawk Chop, a chant that Exeter used in the past, has still been played through the stadium’s PA system despite promises that it was retired.

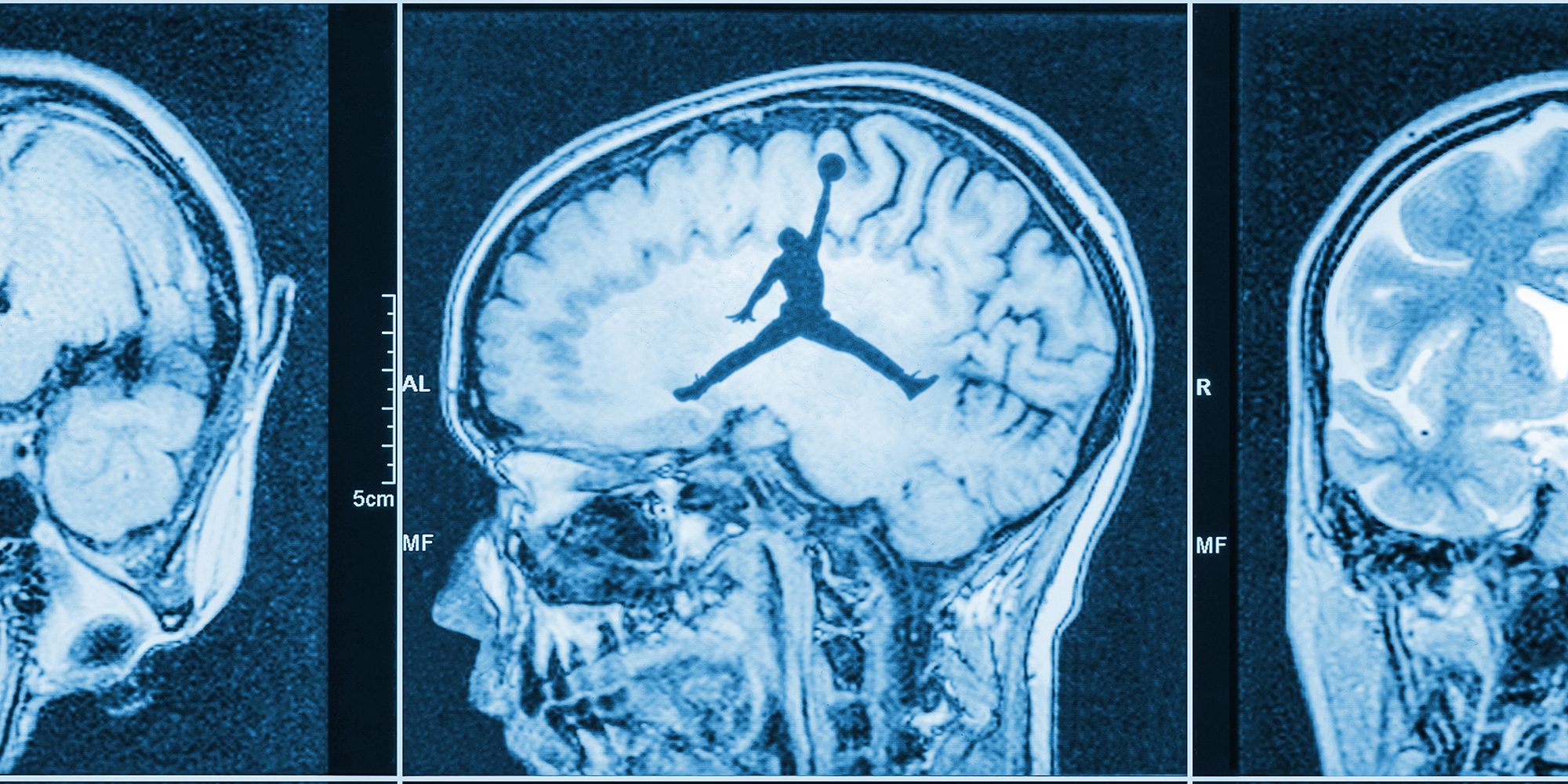

The chant, created in the 1980s by the Florida State Seminoles, has an accompanying ‘chopping’ motion and is used as a hype-up song, encouraging the team to ‘scalp’ their enemies, invoking harmful stereotypes of the Native American ‘savage.’

Lydia Berman, branding expert and founder of Creative Stripes, a UK-based marketing agency, understands that the Chiefs rebrand can’t be a once-off event and will require the club to make a constant effort.

“Attempting to undo decades of racist caricature imagery will not be changed overnight with a new logo,” Berman says.

“Fans need to feel engaged with the change. That takes time to filter through. With sports in particular, fans carry their attachment to colours, phrases, and styling as much as their passion towards the sport overall.”

This rings true, particularly with the Tomahawk Chop still leading the teams onto the field.

While the Exeter Chiefs have been reached out to since the rebrand to address these concerns, each message is met with “no one from the club will be making any further comment” on the rebrand, from media and communications officer Mark Stevens.

The future of rugby

While many have seen this as a positive step for more empathy and understanding in rugby, many fans, unsurprisingly, have seen it as liberalism run amok.

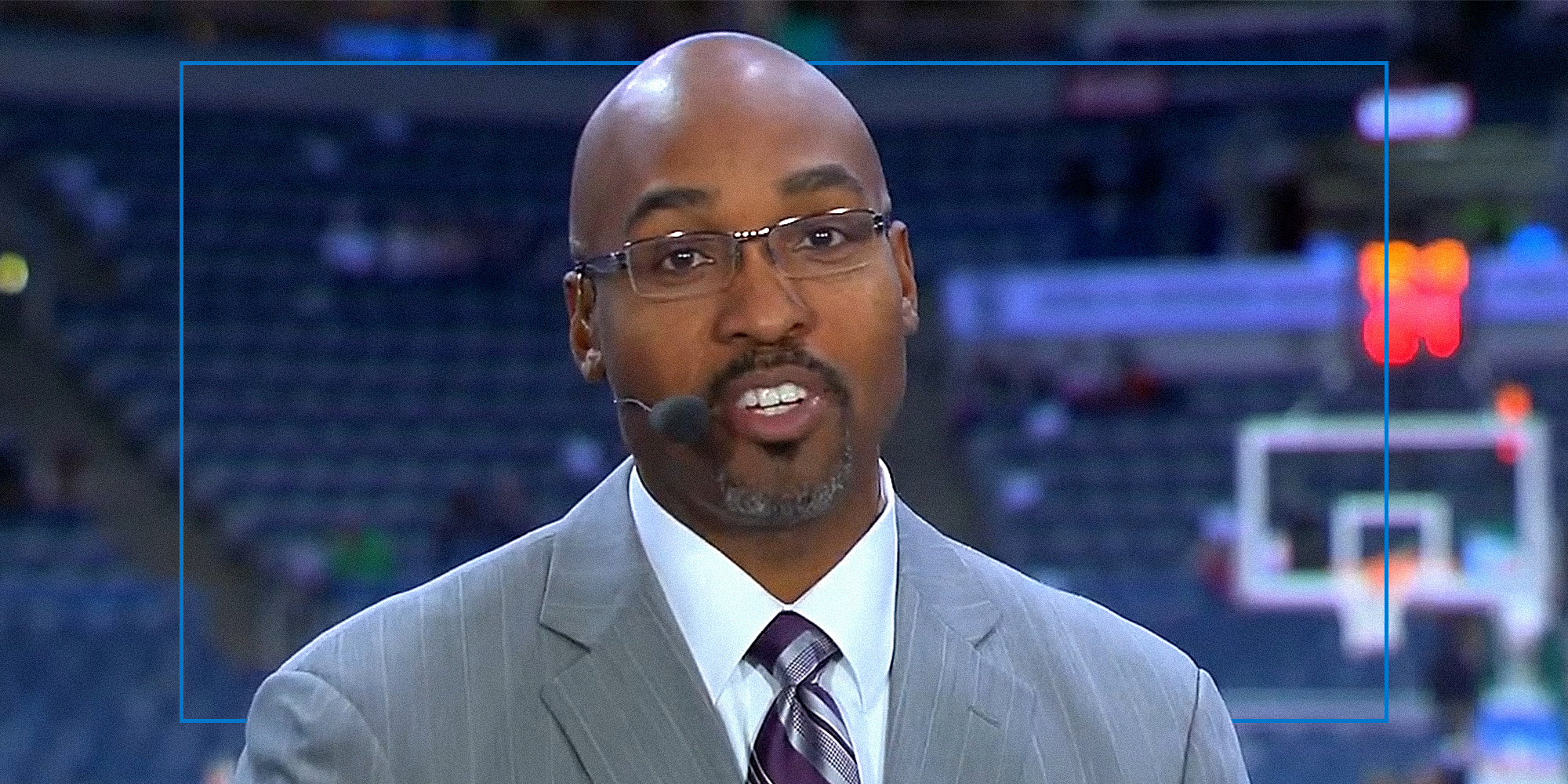

“The general pushback that we got from some listeners,” Lee Calvert says, “was that this was just ‘wokery,’ and that we should be finding something else to be concerned about.”

The Exeter Chiefs branding controversy is a microcosm of a larger issue in rugby, an extension of the belief that ‘rugby values’ make it better than other sports.

Rugby union in the UK has had some particularly bad press recently, with Scottish fullback Rufus McLean pleading guilty to domestic abuse this past December, and the Welsh Rugby Union’s corporate culture of sexism and racism exposed by the BBC in a Jan. 23 report.

“There’s this belief that everyone who plays rugby is a ‘top bloke’ or a ‘good rugby man’ and that somehow, if a person is linked with rugby, they can do no wrong,” Calvert says. The same is often said of rugby teams.

The Chiefs, however, have set an example by doing the right thing – though it will be impossible to know whether it was done with genuine concern or purely for optics.

In the end, Holloway is still showing up for Chiefs games at small pubs in Devon when visiting home. There, she’ll get the occasional snarky comment, along the lines of ‘look what you’ve done,’ as the team sprints out wearing new logos across their chests.

There may be fewer headdresses, but the Tomahawk Chop is still pumped through the PA system, and flags featuring old, harmful imagery are still flown with pride.

Holloway knows that the fanbase is not going to change overnight, and Exeter Chiefs for Change’s mission has now altered somewhat. Instead of changing the Chiefs’ branding, their goal is now perhaps more difficult: To change the hearts and minds of holdout fans.

Chris Jaworski is a freelance rugby writer based in Johannesburg. After moving from Canada to South Africa in 2015, Chris learned his rucks from his mauls (after years of playing gridiron football) and a new love was born. He supports the Lions, the Springboks, and the Canadian National Team (old habits). He can be found most weekends on Twitter (@TheRugbyCat) ranting about rugby.

See more stories from Presser – examining the intersection of race and sports online.