2015 changed the Internet.

The Federal Communications Commission passed strong net neutrality rules, Congress passed the first major surveillance reform in a generation, the use of encrypted communications has expanded, and activists have harnessed the power of social media and data tools to shift the most significant debates in America today in new directions.

All of that didn’t just happen by accident. Scores of unsung heroes tirelessly fought to make the Internet—and, thus, our lives on it—better, freer, and more impactful.

It’s time we highlight the women and men who helped make that happen.

This year, we’ve expanded our definition of Internet freedom heroes to not simply include those who have fought for the issues that have traditionally fallen under that umbrella, like net neutrality or privacy—though there’s plenty of that, too—but also those who have used the freedom that the Internet provides to great effect.

From activists fighting for privacy and citizen journalists fighting against the Islamic State to attorneys, academics, lawmakers, and more, here are the people who helped make the Internet a better place for all of us in 2015.

“I’ll never forget the day that [the FCC] voted,” Gigi Sohn recalled of Feb. 26, the historic day when, thanks largely to Chairman Tom Wheeler’s political leadership and Sohn’s behind-the-scenes work, the Federal Communication Commission voted strong net neutrality rules into law. “There was supposed to be a pretty bad storm here in D.C. I came all wrapped up, wearing boots. … The joy in the building was remarkable,” she told the Daily Dot. And with good measure—the pressure to create real net neutrality rules was by orders of magnitude the largest public outcry the FCC had ever seen.

At the time, Sohn had been with the commission for 14 months. In reality, this was the culmination of some 15 years of work. Back in 1999, when she was a project specialist at the Ford Foundation funding NGOs that fought for Internet freedom, the notion that Internet providers shouldn’t be able to charge different rates for different types of traffic was called “open access.” Academic and futurist Tim Wu wouldn’t coin the term we now call it— “net neutrality”—until 2003.

From there, Sohn moved to become the head of Public Knowledge, a public interest group concerned with Internet freedom, which often meant fighting for net neutrality—and criticizing the FCC.

While activists feared Wheeler was too compromised a political figure to really fight for public interest—he had served as a telecommunications lobbyist and was named to his post after working as a fundraiser for President Barack Obama—his decision to hire Sohn was a clear sign of his priorities.

Only a few weeks after Sohn started, a court overturned a previous FCC attempt to enshrine net neutrality. It was a blow to the Commission—but now the commission had her on its side.

“I don’t think the chairman hired me because he thought the rules would be overturned and because he’d have to put new ones into law,” she said. “He hired me because he knew how important it was have somebody who had the respect of the public interest community and also the industry. He wanted somebody who was an expert substantively, but his main job was going to be communicating with the outside world—who was from the field, so to speak.”

“Obviously, there have been some serious bumps along the way,” Sohn said. “So to see it manifest itself in 2015 in this way, and to be working for the guy who did it, has obviously just been remarkable.” — Kevin Collier

Sen. Rand Paul has single-handedly elevated civil liberties to the presidential debate stage.

The Republican primary is full of candidates who talk tough on national security and warn that Americans will have to give up more of their privacy in order for the government to fight terrorism. Paul, the Senate’s libertarian privacy hawk, has rejected that argument, adapting his Senate crusade against government overreach into a potent campaign-trail narrative.

Paul protested the renewal of the USA Patriot Act, a sweeping post-9/11 surveillance law, for more than 10 straight hours on the Senate floor. He inveighed against what he called a surveillance state run amok in the floor debate over the USA Freedom Act, a major reform bill that ended a National Security Agency’s bulk phone-records collection program but did not go far enough for Paul’s liking. And he tangled with New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie over surveillance and the Fourth Amendment during the heavily watched first Republican debate, in an exchange that became the night’s most-tweeted-about moment.

The 2013 Edward Snowden revelations about the far-reaching U.S. surveillance state turned a once-obscure technology policy issue into a dinner-table debate. But the Snowden leaks lost their potency as Americans began to perceive a greater terrorist threat from ISIS. In a year bookended by twin terrorist attacks in Paris—in addition to a December shooting in San Bernardino, California—the pendulum swung away from privacy and back toward security. But Paul, who praised Snowden for doing “a service” to his country, isn’t giving up.

Whether or not he wins the Republican nomination in 2016, Paul’s privacy-minded criticism of surveillance policy in 2015 will have helped raise that issue’s profile to the summit of American politics. Every near-term victory for surveillance-reform activists will owe something to him. — Eric Geller

Matt Blaze has been on the front lines of the most important questions in computer security for over two decades.

Earlier this year, Blaze warned Congress that the state of computer security is “an emerging national crisis.” In the midst of an intensifying debate over the future of encryption, he argued that the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s insistence on backdoors in encrypted technology would “weaken our infrastructure” and ultimately benefit “criminals and rival nation states” rather than Americans.

This month, Senate Intelligence Chairman Richard Burr (R-N.C.) and Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) promised new legislation that would “pierce” through encryption. The impending bill makes Blaze an even more important figure when it comes to the future of the Internet.

In the early 90s, the National Security Agency developed the “Clipper chip,” a piece of hardware designed to provide a backdoor to encrypted computers, phones, and every other device a person might own. Only the government was supposed to be able to access the Clipper chip’s secret key.

In 1994, it was Blaze who published a paper exposing several of the Clipper chip’s profound insecurities that made it easy for any hacker to use it. More attacks followed, and the program was eventually abandoned, serving as the classic example of why experts like Blaze regard backdoors—intentional weaknesses in encryption technologies—as immensely dangerous.

What happened to the Clipper chip is a crucial piece of history to be remembered at a moment when the United States—and the entire world—is considering the future of encryption.

Blaze, an associate professor of computer and information science at the University of Pennsylvania, is stepping up to the plate in a big way, taking a vocal stand in the public square against proposals to add government backdoors to encryption technology.

“There is overwhelming consensus in the technical community that even ostensibly ‘secure’ backdoors put the systems into which they are incorporated at increased risk of outside attack and compromise,” Blaze wrote in the Washington Post. “At best, a backdoor greatly increases the ‘attack surface’ of the system and creates rich new opportunities for unauthorized exploitation of hidden (and inevitable) software bugs, to say nothing of the human-scale processes that manage the access.”

As we step up to a crossroads on the future of computer security, there are few more experienced and important voices guiding the way forward than Matt Blaze. — Patrick Howell O’Neill

Armed with little more than an Internet connection, a few dozen well-placed colleagues, and a desire to tell the truth, Mohammed Saleh may be ISIS‘s worst nightmare.

Speaking to the Daily Dot from a location outside of his native Syria, Saleh—a pseudonym he uses for safety—said that, in the months after the Islamic State invaded Raqqa, Syria, in early 2014 and declared it the capital of its growing caliphate, the city was effectively cut off from the world at large. The only link between Raqqa and the rest of that planet was its own social media channels, which the group used as a recruiting tool to attract people around the world to its cause.

Owing largely to ISIS’s brutality, Syria is one of the most dangerous places in the world for journalists. The Committee to Protect Journalists found that over 100 Syrian journalists have left the country, and many intentional media organizations have elected not to send reporters there, especially to ISIS-controlled areas. This gap has left an open space for ISIS to fill with propaganda.

Enter Raqqa Is Being Slaughtered Silently.

For the citizen journalists and anti-violence activists behind RBSS, that situation was profoundly dangerous. “There were arrests, beheadings, and crucifixions—a lot of things were happening in the city and we noticed that nobody was reporting about it,” Saleh said. “We made a Facebook page and a Twitter account. We started posting … [photos and videos] about [what] ISIS was doing to the city. We were posting photos, videos about daily life. Documenting their crimes … day-by-day.”

Their social media effort was the only on-the-ground news source in Raqqa and soon sprouted its own dedicated website. The group, which publishes in both English and Arabic, has written stories about spikes in food and energy prices, how the international bombing campaign against oil production facilities in the area is largely ineffective at dislodging ISIS, and how ISIS is shutting down Internet cafes as way to limit citizens’ access to information. In a nation that’s devolved into chaos, the site is one of the few consistent sources of information about what’s happening on the ground.

This journalism is important for both international observers looking for insight into the conflict and the citizens of Raqqa, who sneak access to the site to learn about what’s happening in their own city.

Since its inception, RBSS has been targeted by ISIS. They’ve been accused of blasphemy and had bounties put on their heads. Numerous members of the group, their friends, and family members have been shot or beheaded by ISIS for their work, including three people living in neighboring Turkey.

The group had over a dozen reporters secretly collecting information in Raqqa and covertly sending what they found to writers and editors outside the country, who assemble and post it online. This division of labor is one way RBSS works to keep its members safe from discovery.

“The citizen-journalists who work from inside Raqqa are risking their lives every day to report and send information to their colleagues outside the country,” Reporters Without Borders told the Daily Dot. “Yet they gave themselves the mission to report the life and monitor violations in Raqqa under ISIS’s control to raise awareness and inform the world about the reality of the ground.”

Despite the risk, Saleh remains resolute. “We will not stop. We will continue to expose them, to post everything bad about them, all the crimes they are committing against the civilians,” he insists. “Maybe we’re fighting in words and they’re fighting in bullets, but we think that every word from us is equal to one bullet from them.” — Aaron Sankin

As a leading technology policy expert, Colin Crowell has championed the use of social media as a tool for human-rights workers, journalists, and whistleblowers to bring live content to the world.

As vice president of Global Public Policy at Twitter, he’s been a vocal opponent of the U.S. intelligence community’s “collect it all” mantra, throwing the full weight of one of the world’s most powerful communication platforms behind reforms that, as he once put it, “protect the right of free expression and reflect global norms with respect to individual privacy and security.”

Recognized in April by the Constitution Project for his leadership on First Amendment and privacy issues, Crowell urged U.S. lawmakers to ensure “government law enforcement and intelligence efforts are transparent, subject to effective oversight, and that rules are narrowly-tailored to meet the legitimate needs of the government in protecting its citizens.”

As head of Twitter for Good, the company’s social responsibility program, Crowell’s leadership has been integral in shaping Twitter’s philanthropic initiatives around the world. His team has worked tirelessly to educate young people about online safety; tackle bullying, extremism, and hate speech; and offer tools to better humanitarian aid during emergencies and devastating natural disasters.

And just today, New Year’s Eve 2015, Crowell announced that Twitter would reinstate Politwoops, a Sunlight Foundation project that keeps politicians accountable by republishing their deleted tweets.

Once referred to by the Washington Post as “one of the most influential tech policy operatives you’ve never heard of,” Crowell was a senior advisor to the chairman of the FCC before joining Twitter in September 2011. Described by former colleagues as ardent defender of U.S. consumers, Crowell’s hand in molding the nation’s communications laws cannot not be overstated. — Dell Cameron

Estelle Massé stood before the European Parliament to explain the future of human rights.

Just weeks earlier, 130 people died in terrorist attacks in the heart of Paris. France adopted a spate of new surveillance laws over the past year. The latest burst of violence provoked a state of emergency and talk of taking new steps to enact restrictive laws in the name of stronger security.

Massé, a 26-year-old Frenchwoman from Normandy who works as a policy analyst with the civil liberties advocacy organization Access, argued that Europe’s legislators should resist the urge the pass countless sweeping security laws that openly curtail the rights of European citizens and, in many cases, demonstrably would not have stopped the attacks in Paris.

“We have learnt the hard way that fast-tracked, short-sighted legislation harms users’ rights, undermines legal certainty, and weakens the basis of our societies,” Massé said. “Consider the government reactions to previous attacks—including those in Mumbai in 2008 and New York in 2001. … Years later, we are still trying to roll back many of those hastily made decisions.”

Well before the current fight over surveillance, Massé had already made a deep and lasting mark on Internet freedom in Europe.

She began her time at Access working on, and then helping to lead, the effort to pass groundbreaking legislation protecting net neutrality in the European Union. It worked. She’s now pushing for strong protections when the law is implemented. She’s also fought legal and political battles against dragnet data retention across Europe as the continent adopts more aggressive surveillance laws.

With the deep impact felt by recent terror attacks, her December 2015 testimony to the European Parliament may be her most powerful moment yet.

“As many French, I felt helpless in front of these attacks and acknowledge the need for reforms. Changing our way of life in response to these attacks would make us live in fear, not freedom. We must respond by being more vigorous in defense of our values and principles. Today, more than ever, we need leadership to address our security challenges. The answer must be one that upholds human rights. If not reformed, the surveillance measures already adopted in the EU will continue to interfere with users’ right to privacy and freedom of expression.”

Our safety is not the only thing that needs fierce protecting, Massé argues. We must also fiercely “protect our most cherished values and human rights.” — Patrick Howell O’Neill

A few years ago, ‘revenge porn’ wasn’t even something that happened. Now, the scourge of nonconsensual pornography is so common in the U.S. that its victims often feel terrorized by the Internet.

But as emerges a villain, so rises an opposing superhero. Or, in this case, three superheroes.

Holly Jacobs, Mary Anne Franks, and Carrie Goldberg make up the core team at the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative (CCRI), a nonprofit that has become one of the nation’s most powerful forces behind a new wave of Web-focused legislation in the mere two years since it was launched in August 2013.

CCRI isn’t just leading the fight against perpetrators of an emerging crime—which typically consists of an ex-partner posting intimate nude or sexualized photos of a woman online without her consent—they are also helping to write and update the laws that are used to prosecute them. Over the past couple of years, 26 U.S. states passed laws criminalizing nonconsensual pornography. Mary Anne Franks, a law professor at the University of Miami and CCRI’s legislative powerhouse, helped create eight such laws in 2015 alone, along with the first federal revenge porn bill.

While Franks travels the country crafting legislation and consulting with leading tech companies to help them update policies regarding revenge porn (something Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, and Google all did this year), her CCRI colleagues are fighting on the ground. Founder Holly Jacobs fields daily correspondence with revenge porn victims who reach out for help via CCRI’s “End Revenge Porn” Web campaign and hotline, writes op-eds, and speaks with the media about the personal impact of revenge porn. Attorney Carrie Goldberg handles an impressive caseload as one of the only lawyers in the country expertly versed in the emerging legal field where digital privacy law intersects with harassment and abuse.

“When I first started coming in contact with other victims of nonconsensual pornography,” Jacobs told the Daily Dot, “it felt as if I had been suffering and wandering alone in a dark and terrifying space for three years and had finally stumbled upon others living in the same nightmare. We had a lot of ‘Me too!’ exchanges with one another regarding the details of our experiences, the emotions we felt, and the reactions we’d encountered from family and friends.”

Much of the success on the legislative front is due to Franks’ relentless work, and in 2016 she plans to increase her work with state legislators while also helping to ensure the passage of the federal bill.

“In all of my work, I continue to challenge elitist and sexist interpretations of free speech and privacy,” Franks told the Daily Dot, “that ignore the silencing and surveillance effects of online harassment on women and minorities.”

Goldberg’s superpower allows her to “paralyze trolls” and “conjure protective force fields around trauma victims,” she told the Daily Dot. She also wins cases—and as CCRI’s only practicing attorney, she brings a “down and dirty litigation perspective” to the board. In 2015, Goldberg worked with victims (of revenge porn, sexual assault and harassment, and related issues as pertaining to online abuse) in 21 criminal cases in addition to her usual roster of family court cases. There were big wins: for a teen victim going up against a major tech company, for three Title IX cases against high schools, in a murder trial that involved what Goldberg called a “rape tape.”

“Many of my clients are indeed victims of revenge porn and/or sextortion,” Goldberg said, “But my average case tends to be more involved than just removing naked pictures from Facebook or a revenge porn site.” — Mary Emily O’Hara

In 2004, Nick Merrill ran smack into one of the most powerful surveillance tools in the United States government’s arsenal.

Merrill, who was then president of Calyx Internet Access in New York, received a National Security Letter (NSL) demanding private customer records along with Merrill’s unequivocal silence about his receipt of the letter. He wasn’t able to tell even his family or lawyers about it.

Since 9/11 and the passage of the USA Patriot Act removed virtually all oversight of the FBI’s use of the letters, the National Security Letter has become a popular and dominating tool used over 300,000 times, according to the Electronic Frontier Foundation. Vast information is demanded, silence is required, and challenges are nearly nonexistent. It’s easy to see why law enforcement likes the letters.

And then came Merrill.

Merrill defied the order of silence and asked the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) for help. As a result, he became the first person to challenge NSLs in court. Just this month, his legal efforts resulted in a federal judge ordering the public release of exactly what the FBI was demanding from Merrill’s company as part of the National Security Letter he received.

The answer was big. The FBI wanted the target’s complete Web browsing history, records of all online purchases, and the IP addresses of every person his customers ever corresponded with.

There was no warrant or court oversight over the powerful letter. Instead, all it takes is an agent’s signature promising that the information will help an unspecified investigation.

“Internet users do not give up their privacy rights when they log on, and the FBI should not have the power to secretly demand that ISPs turn over constitutionally protected information about their users without a court order,” Merill said in a statement. “I hope my successful challenge to the FBI’s NSL gag power will empower others who may have received NSLs to speak out.”

Merill’s long legal war meant years of forced silence. But with a key battle won, he took the time to speak out vocally on why a lack of oversight and balances has resulted in vastly expanding FBI surveillance power.

“The FBI has interpreted its NSL authority to encompass the websites we read, the Web searches we conduct, the people we contact, and the places we go,” Merrill said. “This kind of data reveals the most intimate details of our lives, including our political activities, religious affiliations, private relationships, and even our private thoughts and beliefs.” — Patrick Howell O’Neill

Alison Macrina was working as a librarian at the Watertown library in Massachusetts when the revelations of Edward Snowden shocked the world. “I was like, ‘Oh my god, this problem is bigger than anyone could have imagined,” Macrina told the Daily Dot. “And maybe there’s something that we in libraries can do about this.”

With the help of the Massachusetts American Civil Liberties Union, Macrina started teaching a computer privacy class for her patrons. That’s when the idea for the Library Freedom Project was born. “I very quickly realized that I needed to scale up what I was doing. The computer privacy classes were super popular at my library,” Macrina said. “I figured it was something I could teach to other librarians”

This January, Macrina scored $244,700 in grant funding from the Knight Foundation. Since then, she’s visited libraries around the world and has taken on a major government agency looking to stifle Library Freedom Project’s work.

In addition to teaching classes that empower librarians to inform their patrons about security and privacy in the digital age, Macrina teamed up with the Tor Project and long-time Tor volunteer Nima Fatemi to start putting Tor exit nodes and Tor software in libraries. The Tor network encrypts users’ traffic and routes it through layers of nodes around the world. Exit nodes, the computer where Tor traffic exists into the open Internet, are considered one of the most important—and potentially dangerous—parts of the network.

“So Nima and I were like ‘Yeah, Tor nodes in libraries, this is really a great choice,’ because … libraries are democratic institutions in their communities and sometimes the best examples of them,” Macrina said. “Libraries have spent decades fighting for privacy and speech and intellectual freedoms. So the symbolic nature of it is really there. And the practical side is that libraries are also educational centers.”

The Library Freedom Project started the pilot program for their Tor relay project in Kilton Public Library in New Hampshire, and was quickly met with opposition. Not from the board of directors, who unanimously approved the project, or the libraries patrons, but from the Department of Homeland Security and the local police.

“The library, understandably, was really shaken by this,” Macrina said. “This was never something that was in our threat model when we got started.”

The Kilton Public Library temporarily took down the Tor relay node after their meeting with the local police. At the next library board meeting, over 50 patrons came in support of the project, holding signs like “DHS is not the boss of my library!,” according to Macrina. The relay was reinstated, to the cheers of its supporters.

In the coming year, the Library Freedom Project plans to expand its quest to revolutionize the library in the digital age and further inform librarians around the world about digital privacy and security. — William Turton

At the beginning of 2015, the fate of net neutrality in the United States stood in a precarious balance. It seemed that any day the Internet would be governed by a new set of rules meant to benefit the country’s wealthiest and most powerful media and telecommunications companies, leaving the cards stacked against small businesses and fledgling startups.

Among those speaking out against this new form of high-tech discrimination, few were more vocal than the National Hispanic Media Coalition (NHMC), an organization that saw the death of net neutrality as particularly threatening to communities of color—Americans historically under- or misrepresented in the mainstream.

At a hearing on Capitol Hill in January, Jessica Gonzalez, NHMC executive vice president and general counsel, urged the U.S. House of Representatives to step aside and let the Federal Communications Commission establish rules to preserve the Internet as an all-inclusive and democratizing force.

At the same time, lawmakers were determined to pursue their own deceptively-titled “net neutrality” legislation that, as Jessica testified, could have irrevocably stripped “our country’s expert communications agency of authority to protect consumers on the communications platform of the 21st century and pour cement on the still vast digital divide.”

Needless to say, the defense of net neutrality put up by Jessica and NHMC was integral to ensuring affordable and open Internet access for generations to come.

In June, Gonzalez was on the Hill again, this time testifying before a U.S. Senate subcommittee on the importance of Lifeline, a subsidy that helps to provide low-income Americans with landline and cellphone service. The program is part of a larger effort to close what’s known as the digital divide, a gap into which millions of Americans without consistent phone or Internet access fall.

“I know firsthand how life-changing it can be,” said Gonzalez, crediting Lifeline with helping her find a job, and ultimately earn a law degree, after being laid off from a teaching job in 2004. “It is past time that the federal government took serious steps to address the affordability of broadband for low-income families,” she testified. “Tomorrow is too late. We must act boldly, and we must act now.”

Gonzalez originally hails from Los Angeles where NHMC, now the country’s leading media advocacy and civil rights organization for the advancement of Latinos, was founded in 1986. She currently lives there with her husband and their two children. In September, she was recognized by Slate as one of the “Women Who Won Net Neutrality.” — Dell Cameron

In August 2014, following the fatal shooting of 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, at the hands of a police officer, DeRay Mckesson and Johnetta Elzie rose to prominence as activists in the Black Lives Matter movement. This year, they made it count.

The duo used social media to engage and connect people while they protested the death of Brown on the frontlines of the Ferguson unrest. But protesting was only the beginning. Over the past year and a half, they have not only fought for freedom of information on the Internet—they used its power for change.

The dynamic duo harnessed the power of online information to organize, mobilize, and to create solutions to the issues surrounding one of the most pressing debates in America today: police violence.

“We’ve seen in the movement as a proof of the power of an open Internet to allow for issues that would otherwise be invisible to be rendered visible,” Mckesson told the Daily Dot.

“We’ve been able to spread information,” he added, “to amplify messages and to connect with each other in ways that changed both the national conversation about race, policing and identity, and that are starting to lead to changes.”

Their work eventually coalesced in the form of We The Protesters, one of the most significant activist groups in the BLM movement.

“I didn’t even call myself an organizer,” Elzie told the Daily Dot in September. “I didn’t even know that was a thing, never really cared about it.”

Elzie used the reach of social media to crowdfunded money for supplies for protesters and documented with Mckesson what was happening in Ferguson as it unraveled.

“I can only imagine if the Internet was prohibited in any way in August of 2014 or since then,” Elzie told the Daily Dot in a recent phone interview. “Social media is definitely the driving force in making a bigger difference in this moment versus other moments in black history when black folks have resisted. It was so easy before to pretend that these crimes of injustice aren’t happening.”

Their activism didn’t stop on Ferguson streets in 2014. Mckesson and Elzie, along with Brittany Packnett and Samuel Sinyangwe, created Mapping Police Violence, a grassroots platform addressing the failures of government agencies by reporting comprehensible data on police killings by city and race.

The grassroots effort led to the release of a report on police killings in 2015, which found at least 1,152 people killed by the police, a disproportionate number of them black.

Mapping Police Violence is only one platform created by We The Protesters. They launched Campaign Zero in August, another grassroots effort. The platform highlights presidential candidates’ policies on police violence and focuses on a 10-part solutions plan from activists and research organizations.

Next, We The Protesters had a meeting with Muckrock, an organization that helps people file Freedom of Information Act requests. Armed with that knowledge, Elzie and Mckesson began compiling a database of police union contracts, highlighting how these contracts can fail to hold police accountable.

“It was this idea that no one had ever had before,” Elzie said. “They were just so excited, and we were excited to work together.”

We recently launched The Police Union Contract Project. Learn how they block accountability https://t.co/FbQpkPKN5b. pic.twitter.com/NytIhkOAkr

— deray (@deray) December 11, 2015

The result is the Police Union Contract Project, created to “check the police.” According to Elzie, the platform definitely drew an huge reaction from supporters—and the police.

“The police or whoever handles the union contracts or giving them out, they were instantly on alert like, ‘There’s this group of people pulling contract after contract after contract,’” Elzie said. “But they couldn’t keep that from us.” — Deron Dalton

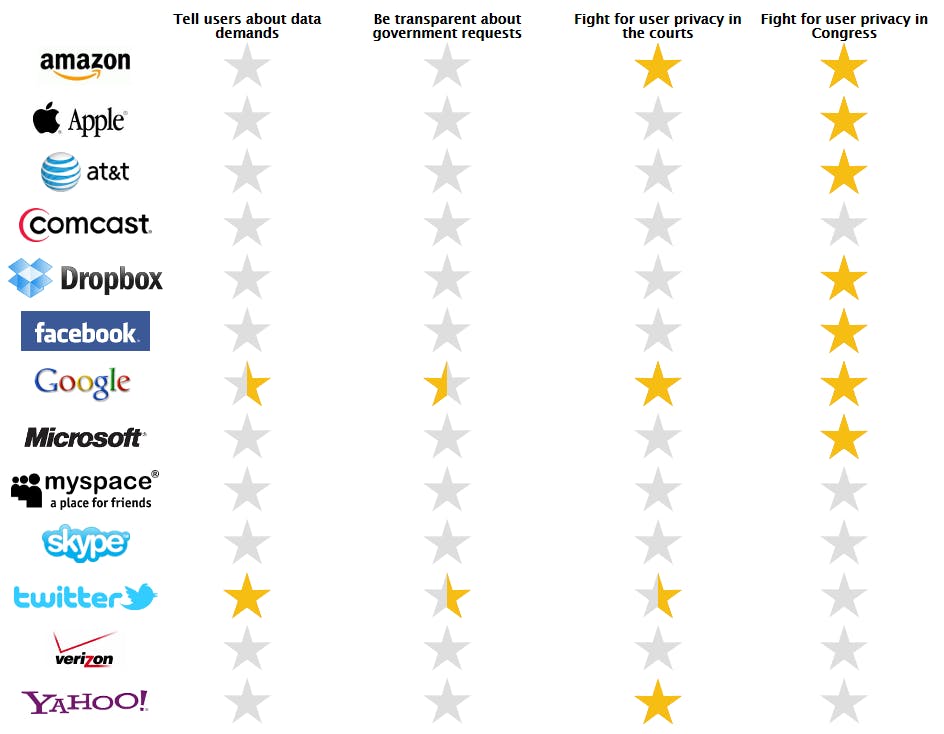

When the Electronic Frontier Foundation first launched its annual Who Has Your Back? report back in 2011, the goal was relatively straightforward: Show Internet users how well high-profile companies protect their data from the government. If a social networking site wanted to prove how strongly it fought to keep your data safe from the prying eyes of government snoops, the Who Has Your Back? report was the way to do it.

“We have to trust these providers with our data and so the question that we had is: Are they actually deserving of that trust?” Nate Cardozo, an EFF staff attorney who compiles the report, told the Daily Dot. “Are they doing everything they can and should in order to protect our data when the government comes knocking?”

In the report’s first year, the EFF only evaluated companies on four criteria and the results weren’t particularly encouraging.

Over the next four years, the report has filled with gold stars as much of the tech industry has developed an increasing commitment to fighting for users’ rights.

Cardozo notes that, every year, an increasing number of companies, such as California-based ISP Sonic.net, are working with the EFF to actively change their policies as a way to maintain high scores.

The report is actively pushing companies to do better.

When cloud-storage service Dropbox took heat for appointing to its board of directors former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, who had spoken positively about government surveillance efforts, the company suffered a backlash from people who feared the move meant a greater willingness to acquiesce to all government data demands. Dropbox was able to push back against those criticisms by pointing to the perfect score it received on the report as evidence of how seriously the company took its responsibility to guard user data—making it more attractive to both users and potential employees.

“A lot of these companies … view each other as competitors,” Cardozo said. “This is a functioning market, and the companies have come to realize that the market demands they respect privacy. The market demands that they treat users and user data with respect. The market now has a metric.” — Aaron Sankin

It often feels like there’s a sound barrier between Washington, D.C., and the corners of the Internet inhabited by privacy experts. Over and over, you hear the same calls from people like FBI Director James Comey or Senator Tom Cotton (R-Ark.)—the U.S. must mandate, by law, that any American company that offers encrypted communications has to have backdoor that lets the government peer inside the protected digital walls.

But Congressman Ted Lieu (D-Calif.), one of four members of Congress with a degree in computer science, knows what cryptographers have said since the beginning. “It is simply not possible to design an encryption system for only the so-called ‘good guys’ have a backdoor access key,” Lieu told the Daily Dot. “Once you weaken that encryption system with a backdoor access key, then not just the good guys, who have it, but potentially any hacker or terrorist can figure it out as well.”

Lieu has stressed this more than any sitting member of the House, and made headlines when he furiously told Comey during a hearing to “just follow the damn Constitution.” Because for him, it’s not just a technical issue—it’s a moral one.

“I believe in the Constitution of the United States, and the Fourth Amendment is pretty clear,” Lieu said. “It basically says that government shall not engage in unreasonable searches and seizures unless the government has a specific warrant for you.” Lieu stresses that he found it a clear violation of Americans’ civil liberties when Edward Snowden revealed the NSA was accessing Americans’ phone records in bulk without a warrant.

“Privacy is one of the defining issues of the 21st century,” he added. “With the amount of technology that’s in our daily lives now, it’s going to continue to be an important issue, and I think we need to make sure that the Fourth Amendment is respected whether people are using pen and paper or using computers.” — Kevin Collier

Since the 2013 revelations of Edward Snowden, an increasing number of everyday people feel the prying eyes of government surveillance as a constant threat to their privacy. That’s where Open Whisper Systems comes in.

Encryption is a mathematical algorithm that scrambles the content of your messages, making it so the intended recipient is the only person who has the key that can unscramble the message. Just five years ago, encrypted messaging was a mess. One of the only real options was an encryption protocol called Pretty Good Privacy, or PGP. And it was just that. Pretty good, but not great. It was cumbersome, difficult for technically disinclined people to use, and knowing the identity of the person you were messaging wasn’t always clear.

Open Whisper Systems has changed the game, making state-of-the-art encryption accessible to everyone and dead-easy to use. In a time where lawmakers are falling over themselves to regulate encryption roll back privacy protections, Open Whisper Systems have launched a new era of privacy online.

Open Whisper Systems was founded by Moxie Marlinspike, the former head of product security at Twitter and an encryption expert. The most popular messaging app in the world, WhatsApp, recently implemented the encryption developed by Marlinspike and Open Whisper Systems. (Facebook purchased WhatsApp for $22 billion dollars and the app isn’t open source, so it wouldn’t be privacy advocates first choice when it comes to communicating securely.)

Open Whisper Systems has received glowing endorsements from the academic computer security world and the world’s foremost privacy advocates. “After reading the code, I literally discovered a line of drool running down my face,” Matthew Green, cryptography professor at John Hopkins University told the Daily Dot. “It’s really nice.” Last year, they received some of the highest praise from Snowden himself when he declared that people should “use anything by Open Whisper Systems.”

The company’s flagship product, Signal, is a free instant messaging and calling app with zero learning curve. Download it, and you can start sending encrypted messages or hold an encrypted phone call with anyone else that also has the app. It really is as easy as it sounds.

Signal is open source, which means a community of experts can review the code and the encryption underneath, ensuring there haven’t been any backdoors secretly placed by nation states or malicious actors. They’re funded entirely by grants and aren’t looking for investment from venture capital firm, because doing so may compromise on the security and privacy of their users. The team recently released a beta version of the Signal desktop app, expanding the ways people can send encrypted messages. — William Turton

Correction: Facebook bought WhatsApp for $22 billion.

Illustration by Max Fleishman