Directly in the heart of Moscow, near the Taganskaja metro station, you can meet Katrin. Just send her a message on a website called Dosug and grab your wallet.

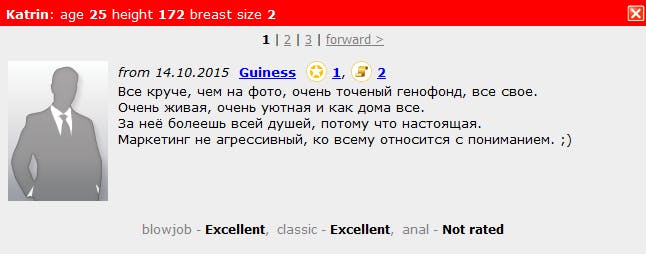

She’s a beautiful, 25-year-old Russian woman who could bankrupt you with her presence.

An evening with Katrin is relatively expensive: 15,000 rubles—about $228—for an hour of her time. But those kind of prices are increasingly common for sex workers in Russia. As the Russian economy and currency sunk over the last several years, the price of prostitution has spiked across the board.

But the sex is “excellent,” according to the reviews on her Dosug profile, so men pay the price.

Dosug (?????, translated as Leisure) is a Russian online brothel centered in Moscow but with operations all around Europe. It can be found on both the anonymous dark net as well as the normal internet, where the website is always trying to stay two steps ahead of Russia’s notoriously vigorous cyber censors.

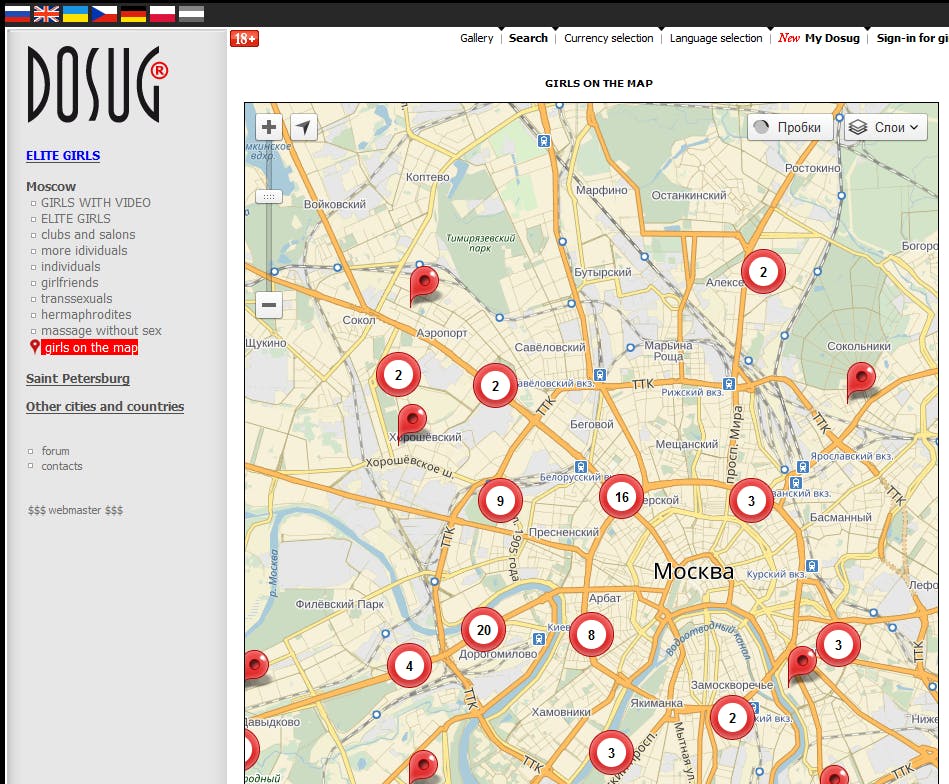

At over a decade old, Dosug serves as Russia’s biggest catalog of sex workers. Its existence means buying anything from a massage to sex is nearly as easy as ordering up a taxi on your phone. Dosug’s map of nearby available prostitutes looks an awful lot like Uber‘s map of available drivers.

Every business sells a product. Dosug’s is sex work 2.0.

Uber revolutionized hailing cabs on your phone. Silk Road forever changed buying drugs on the dark net. Websites like Dosug take a page from both to bring the world’s oldest profession into a high-tech, low-life 21st century.

Dosug was created by Konstantin Rykov, a 37-year-old Russian internet entrepreneur and politician who, until 2011, served as a legislative deputy in President Vladimir Putin‘s United Russia party and worked in the Duma Committee on Science and High Technologies.

Rykov, who first learned about the internet in a 1995 state-sponsored trip to the United States and fell deeply into IRC chat networks, is a one-of-a-kind beast who fits strangely well into the wonderland circle of Kremlin influence and ideology.

Starting in the 1990s, Rykov built a kingdom of popular websites beginning with fuck.ru, an obscenity-laced website that flaunted Russia’s rules while he operated under the psuedonym Jason Foris. He expanded into website design, advertising networks, book publishing, television, and eventually hundreds of other internet projects, according to his own count.

Among other news websites, Rykov runs ?????? (Sight), referred to around the Western world as a mouthpiece of Putin’s Kremlin. He dubbed Russia’s annexation of Crimea as the “Russian Spring.”

But it’s Rykov’s collection of porn, erotic, and prostitution sites, among others, that sets him apart.

“I make in a night as much as Yandex makes in a year,” Rykov told a Russian journalist in 2011 when discussing his internet empire. Yandex, Russia’s version of Google, is a multibillion dollar company. During that interview, Rykov listed websites to his credit including Dosug.

Not much about the inner workings of Dosug today is clear. While Rykov founded Dosug, it’s not definite that he’s still running it. Neither Rykov nor Dosug’s current operators responded to requests for comment.

When I asked Dosug’s social media team if they had anyone who spoke English to talk with a reporter, they assured me, “most of the girls on our site are polyglots, try them if you want, but they prefer doing some interesting things over talking.”

Listing prostitutes online is nothing new. Sites likes Craigslist, myRedBook, and Backpage are just a few iconic names in a long, global list of websites that have been advertising sex work for years.

Until 2015, however, none of those sites used the Tor network.

Often synonymous with the dark net—the sites, services, apps, data, and files not indexed by search engines like Google—Tor masks users’ identities through encryption and a unique routing scheme that makes it difficult to connect you to the sites you visit and the things you do there. It also enables so-called hidden services, sites that are only accessible with the use of a specialized Tor Browser designed to grant privacy, anonymity, and security far beyond the likes of Chrome or Firefox.

A wide range of people use Tor, including journalists, human rights activists, soldiers, governments, criminals, and terrorists.

In a bid to beat Russian censors—who had already taken down dozens of other versions of the site—Dosug leaped over to the dark net. It’s had a home there ever since, even after Dosug re-established itself on normal websites by doing business from countries like the Czech Republic, where prostitution is legal and lazily regulated, and Cyprus, where the laws on prostitution are vague and often unenforced.

Being close to the Kremlin doesn’t automatically grant you favor when it comes to internet censorship. German Klimenko, Putin’s own internet advisor, runs a BitTorrent tracker that’s offered pirated content. The site has been blocked at times during copyright disputes.

Dosug has existed and thrived in one form or another for 17 years. Last year’s move to the dark net was just another evolution necessary to survive and thrive.

The move is immediately reminiscent of the dark net markets famous for selling drugs, guns, and data around the world in exchange for bitcoins. The godfather of those sites, Ross Ulbricht, was a fiercely politicized activist when he created Silk Road in 2011. But unlike those markets, Dosug takes dollars, rubles, pounds, and euros. Bitcoin is nowhere to be found.

“Bitcoin is no so popular in Russia for payments,” Anton Nesterov, a Russian programmer, explained, “and I don’t think that Russian customers of sex workers are Bitcoin evangelists. They moved to .onion [the dark net domain] not because they are cypherpunks, but because their main site was blocked in Russia.”

The women on Dosug have their own section of the site where they can place ads, check messages, and do business with Dosug’s tens of thousands of visitors. Videos, user feedback, and heavily Photoshopped pictures guide customers who grade every single thing that goes on.

For Dosug, the dark net is a back-up plan that allows it an out against Russian censors empowered by a 2012 law that created a national internet blacklist.

For Rykov, the site is but one strange line on his résumé among many.