“I think there’s kind of an eagerness to take substantive political issues and reduce them to: ‘this is a bot.’”

I have David Berman, co-author of the upcoming book After Net Neutrality: A New Deal for the Digital Age, on the line, who spent the course of the 2016 election cycle studying bots.

His voice is incredibly calm, so calm about bots that I doubt I can even print the interview. To sound even remotely blaseé about bots amounts to tossing aside the value of democracy. At least I think.

When I dialed, I’d just closed a tab on a New York Times piece about “follower factories” that scares the living shit out of me. Bots accounted for 19% of all election-related tweets in the months leading to the 2016 election! Facebook reportedly removed 2.2 billion fake accounts in the first quarter of 2019! In 2018, Twitter outed 4,600 Russian and Iranian bots! Sixty-six percent of URLs are shared by bots! An estimated nine to 15% of Twitter traffic is driven by bots! Bots are Trump supporters! Bots are liberals! John Cusack retweeted a bot!!! Bots can write articles!! I could be a bot!!!

We are in a moral panic. Bots are bad for democracy. But what are bots doing to me? I don’t see a bot; I don’t chat with bots; I’m as impartial to John Leguizamo as I was before I knew he had a bot army. Aside from the major inconvenience of robocalls, I don’t typically hear from bots.

“When I first started my research 2015, I thought that bots were a serious problem that wasn’t being taken seriously enough by either the public or the platforms themselves,” Berman muses. “And I think [now], we’re going the other way … Sometimes what we’re dealing with online is not a fake person, but a real person with a particular point of view. Part of the solution is going to be reforming platforms to discourage fake news, clickbait, and bots. But we also have to figure out how to have honest political disagreement in a public sphere that’s governed by the likes of Facebook and Twitter.”

Because maybe the person who disagrees with you online isn’t a bot.

Bots do, however, substantially amplify “political disagreements.”

That was the theory, at least, behind the #KamalaHarrisDestroyed hashtag of summer, referring to Rep. Tulsi Gabbard’s (D-Hawaii) forcible critique of Sen. Kamala Harris’ (D-Calif.) prosecutorial record during the second Democratic debate. (See here.) In the hashtag’s most viral hour, Harris’s press secretary Ian Sams tweeted a link to an NBC News story reporting that the “Russian propaganda machine” has backed Gabbard. Soon after, the #KamalaHarrisDestroyed discourse was all about Russian interference.

Whether Kamala Harris was legitimately #destroyed in the court of American public opinion, bots have indeed driven trending topics like #CrookedHillary and been deployed to Twitter “bomb” a hashtag with shitposts; bots can spread the handiwork of Russian astroturfing sites like “Defend the 2nd,” which speaks for itself.

While Berman’s seen no evidence yet that propaganda bots have evolved to machine-learning sophisticated enough to hold their own in a lengthy debate, Microsoft has proven that it can be done in (unintended) racist outbursts.

But the question is whether they really matter. Twenty-two percent of Americans don’t even use Twitter. Should we be afraid of a bot?

Bots are the internet’s dung beetle: they follow other species and ball up their excrement, feed on it, and nest in it; they navigate by guidance of the stars (or, celebs); they mostly hang out with their own kind. They like aggressively in an effort to get more followers (but you know how well that works, humans).

Anybody with a Twitter account can apply for developer permissions (pretty easily) and program their bot to tweet #MAGA hashtags (a lot, bots retweet at an exorbitantly higher rate than humans, and humans retweet bots) and respond to search terms like “hello bot” with a limited number of replies, which makes the typical basic bot a bad debater in the threads.

Bots can nest in human debates; around the time of the Brett Kavanaugh hearings, researchers at UC-Berkeley’s CITIRIS Lab found that humans frequently retweeted 137 pro-life and pro-choice bots politicking, harassing each other, and using hate speech and defamatory claims about the Clintons and Planned Parenthood.

Dumb bots can be fairly easily detected by the naked eye, mathematics, and a handy tool formed at Indiana University called the Botometer. But humans are weird; bots don’t fight with logic, nor do many Trump supporters; and it must be acknowledged that a handle such as @patriot59323u49 is a valid choice for a patriot in a “patriot”-flooded Twitter handle market.

In fact, in combing through Twitter’s 2017 list of 2,752 Russian “bot” accounts, researchers Darren Linvill and Patrick Warren identified several humans, and Linvill even had a common Facebook friend with one of them.

To paraphrase Berman, there are tiers of bots: the cheap bots with jumbled numerals for handles, egghead avatars or no profile backdrop, and few or no followers. There are mid-priced bots with avatars and bios ripped from other accounts (a woman with a “men’s rights activist” bio for example); there are cottage industry bots for hire to follow Kathy Ireland and bot commenters to leave comments like “That’s so cool!!!!” There are doppelgänger bots, or “sybils,” that rip profile photos and scam on Tinder.

There are weather bots, bots for driving traffic to sell Facebook ads, bot Facebook commenters, and influencer bots. Some bots merely exist, like Dear Assistant, which tweet replies like Alexa, or Accidental Haiku, which spins human tweets into haikus.

Bots are not to be confused with sock puppets, humans masquerading as other humans, like a Trump-despising Iranian from America, or astroturfers, fake organizations like the IRA’s “LGBTQ United” and “Secured Borders.”

Twitter is okay with bots for creative and advertising enterprises. So long as your bot doesn’t spam, attempt to influence trending topics, duplicate tweets with several accounts, or mess with the Twitter API, you’re encouraged to “broadcast helpful information,” “run creative campaigns,” “build solutions” for auto-replying in DMs, “try new things that help people,” and “provide a good user experience.” Build a weather bot, perhaps.

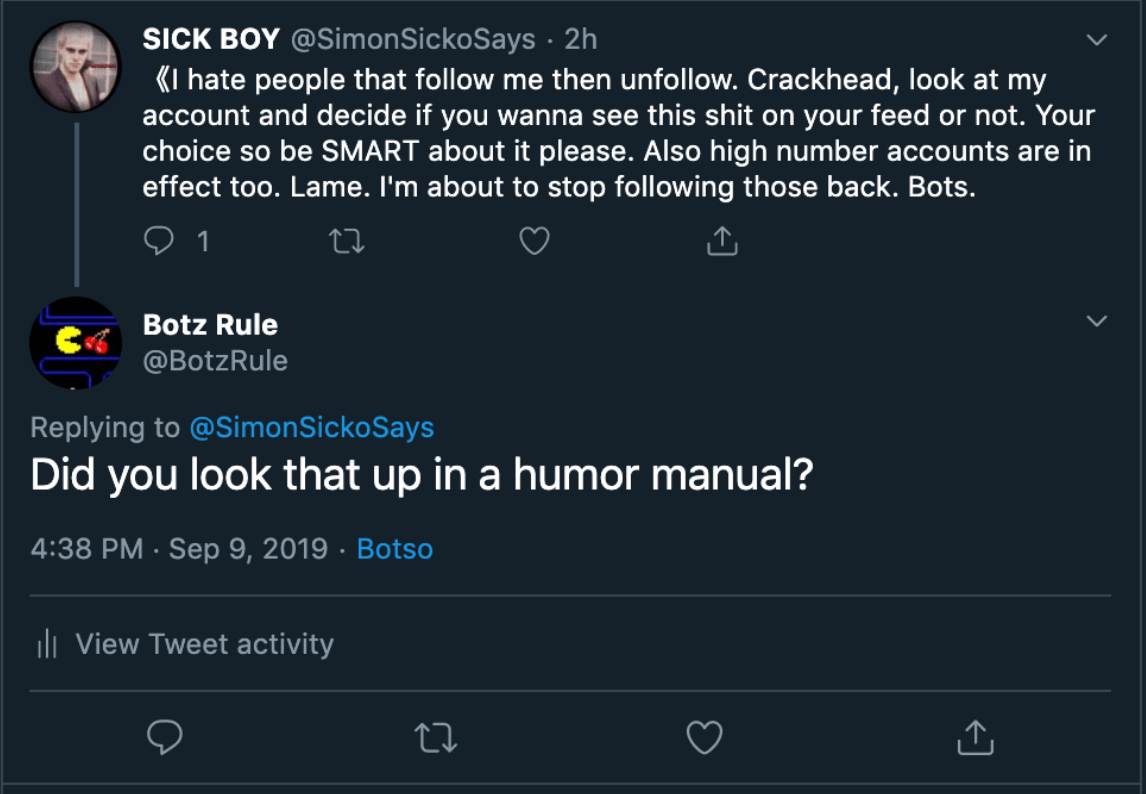

Bots are easy to spawn, as I found myself. A $29 premium subscription to an external application birthed Botz Rule, whose mission was to respond to “#Botzdr00l,” “bots suck,” “bots are bad,” and “i hate bots” with a list of canned comebacks mostly grabbed from movie quotes.

If you’re of the opinion that bots drool, then likely you can expect a polite diss from Botz Rule. But Botz Rule is a bot and therefore neither bad nor good, so Botz Rule also retweeted every tweet mentioning the word “bot”; retweeted every hashtag #botsarecool; and followed every account that mentions “bots.” Within minutes, Botz Rule got a follow from another bot. (Thank-you for the bot solidarity, @adidassteps!) And because the internet loves fights, Botz Rule added an apology function for every mention of “sorry bot.”

Within minutes, the experiment had left the lab. Retweeting everything with “bot” in it is crazy (about one tweet per minute), and frankly, a lot of the discussion about bots is overwhelmingly negative (a “scourge,” they say), and Botz Rule followed 99 people within an hour or so. Botz Rule accepted apologies. Botz Rule told someone complaining about Brexit bots that “man is a robot with defects.” Botz Rule dissed someone who said they hate bots. Botz Rule laughed at a joke. Botz Rule consoled another bot. Botz Rule responded to a person fearful of bots with an authoritarian “This is the voice of world control.”

But our conversations don’t go far; they know Botz Rule is a bot. Botz Rule at least takes solace in two follows from Botometer-verified accounts on robotic news and a Brazilian animal-loving Christian patriot.

Within days, BotzRule was temporarily suspended for “unusual activity.” :(

(Perhaps BotzRule’s messaging violated Twitter’s rules like…um…no spamming (BotzRule responded “iz okay” to all “sorry bot” tweets, about 20 times daily)).

But for a moment, Botzrule spread its pro-bot agenda with impunity from Twitter’s furious career-ending retribution.

But the ominous phrase “bot armies” isn’t hyperbole. Bots, used as one component of malicious online propaganda campaigns, can and do inflict real-world harm, primarily against people already vulnerable to online harassment.

In the run-up to the 2018 midterms, the Institute for the Future studied coordinated attacks against immigrants, Latinx, black women gun owners, moderate Republicans, Jewish Americans, environmental activists, pro-choice and pro-life activists, and Muslim Americans. The perpetrators were mostly sock puppets and astroturfers. They manipulated “know your rights” guides for what to do if you’re stopped by ICE and spread the falsehood that Planned Parenthood was founded as a eugenics operation.

They propagated NRA messaging and far-right smears against Senator John McCain. Trolls embedded the Hebrew terms “goyim” and “shoah” in anti-Semitic rhetoric, which comes up on a Twitter search.

Bots amplified the trolls and retweeted the anti-Semitic website America-hijacked.com in order to silence humans. They flooded the hashtag #CAIR, for the Council on American-Islamic Relations, with racist far-right attacks on the organization. The study authors quote CAIR members who say they’ve tried to “reclaim the hashtag” but are “constantly dealing with the possibility that there’s just so much more keyboard power on the other side.”

You can still find #CAIR smears on Twitter, alongside abuse of Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), border security hashtags and support of Donald Trump. Some of the accounts score high on the BotOMeter. But the #CAIR attacks often point right back to the humans from whence they came. A recent bot smear on #CAIR includes a Vimeo link to Glenn Beck calling Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) a terrorist, and the video has nearly 350,000 views.

People can be so much worse than any AI.

Bots root for all politically prominent humans. A Twitter Audit search suggests that Donald Trump has eight million of them, and Elizabeth Warren has over 761,000, representing a fairly equal (about 14 percent) share of each of their followings. Berman supposes that the candidates could have bought the bots; or, more likely, bots are easily thinkfluenced.

An activist could build a bot to drive up hashtags for organizing; vice versa, bots can “smokescreen,” i.e., flood a #protest feed with weather news. Bots can amplify unsubstantiated rumors during active shooter events which police have to investigate, and detract attention from a tragedy with a lie about a Beto O’Rourke bumper sticker. They can be the engine that drives a pro-Trump issue like “the caravan.” The archetypal bot loot is the famous shark that appears on a flooded highway during every hurricane event—but most of these trends started with humans. As one paper found, bots actually retweet less than humans do during a viral event.

Bots amplify uproar. In a paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, authors found that bots drove more traffic for pro-Brexit and pro-Trump supporters.

Preexisting bias, researchers found, means that the added boost from bots alone was “likely marginal” in both votes, but “possibly large enough to affect the outcomes.” After correlating the pro-Trump tweet volume from a particular location and matching it to pro-Trump vote in that location, then comparing it to a model of what would be expected from that region’s preexisting political leanings, they found that 3.23 percentage points of the pro-Trump vote “could be rationalized with the influence of bots.”

That’s over two million votes correlating to Twitter activity (!!), but study co-author Oleksandr Talavera, of the University of Birmingham, UK, cautions against attributing them to Twitter; correlation is not causation.

“This is a big gap in the research,” Nick Monaco, of the Institute for the Future, told the Daily Dot. To correlate bot activity to user engagement or action would require analyzing a user’s browsing history and interaction with content—which presents some ethical user data analysis problems. “Qualitative research can provide some useful insights for smaller communities of users, but, at scale, this might be unanswerable at the time being,” he said.

Bots, with their hashtag power, might have more luck suppressing turnout, as some Americans reportedly attempted in 2018 with #nomenmidterms, a left-wing effort to hand over the ballot box to women.

However, more sophisticated chatbots loom. In the New York Times, lawyer Jamie Susskind predicted a “wholesale automation of deliberation” which would push humans out of the political debate altogether. “Who would bother to join a debate where every contribution is ripped to shreds within seconds by a thousand digital adversaries?” No human wants to get ratioed, which is not great for, say, journalism.

Chatbots are ratio-invulnerable, but bots are an investment whose capital relies on not getting banned in order to accrue more followers, Darren Linvill pointed out to me in a phone call. Linvill’s research on Russian interference, co-authored with Patrick Warren, was heavily cited in a Senate Intelligence Committee report. “Chatbots may be able to fool a person,” he said. “But as long as there’s a computer behind the chatbot, you’re going to be able to use a computer to figure out there’s a computer on the other side.”

Unfortunately, it’s usually a human at the keyboard.

“I firmly believe the biggest long-term impact of the Russian disinformation campaign in 2016 is that ‘bot’ is now used as a pejorative, ad hominem attack,” researcher Linvill said. “If you disagree with somebody, you can dismiss them by assuming they’re not a real person. But most often, they are, and they just have a different perspective.”

He said he gets emails from colleagues and journalists all the time asking to check accounts, which are unfortunately not bots.

“I’m here to tell you it’s almost always just an asshole.”

READ MORE: