Golf is often viewed as an elitist sport with its path rarely crossing into the realm of civil rights. An online push to save one golf course with an important history in the American South dispels conventional wisdom, and continues to play a role in a larger movement to preserve affordable courses for the less privileged to enjoy.

Occupying more than 140 acres of rapidly expanding Austin, Texas, the full-length, 18-hole Lions Municipal Golf Course opened in 1924. The facility sits on the Greater Brackenridge Tract, 503 acres bequeathed to the University of Texas by Col. George Washington Brackenridge in 1910.

While the university owns the land, the City of Austin has continued to lease it back for Lions Municipal since it took over the course’s lease in 1936. To this day, a full round of golf costs $35 on a weekend and $28 for weekday play.

With that leasing arrangement expired, the city and the university continue to discuss a new agreement. The SaveMuny community looks to rally public support for Austin’s effort to extend leasing terms. If the two sides cannot find common ground, the university would reclaim the land outright. While no one at the University of Texas publicly stated it would be the end of Lions, the people behind SaveMuny don’t see the Longhorns using the Brackenridge land for golf, regardless of its civil rights significance.

While the course remains popular with locals, its historical significance keeps it on the national radar. Lions Municipal is recognized by the National Parks Department as the first desegregated golf course south of the Mason-Dixon Line, breaking down the racial barrier in 1950.

But in 2022, the course’s location near the Colorado River makes it prime real estate for development. The struggle between the university, Austin officials, and the course’s supporters has one of golf’s significant social justice landmarks in peril.

World Golf Hall of Famer and two-time Masters winner Ben Crenshaw grew up playing Lions. He now co-chairs the Muny Conservancy and the SaveMuny.com online effort. Crenshaw reports that the University of Texas and local government are negotiating on zoning for other university-owned parcels in town, raising hopes that a compromise could arise to preserve all 18 holes.

“I grew up three blocks from Lions and split time playing there and at Austin Country Club from age 8 through my college years at Texas,” Crenshaw tells Presser. “I still play there occasionally to this day and enjoy going by to watch the kids learning golf at the Austin Junior Golf Academy or the high school teams that call Muny their home.”

As a Longhorn alum, Crenshaw insists he loves the university, but is disappointed this issue remains unresolved.

“We understand that [the University of Texas] owns the property and that it’s a very valuable piece of land,” Crenshaw explains. “But, the course is a civil rights landmark. It cannot become strictly a monetary consideration. This is a tremendous opportunity for the U of T to step up in the community.”

When contacted for a statement, representatives of the Austin Parks and Recreation Department referred any questions to the city attorney’s. The legal team did not respond.

Director of Media Relations and Issues Management for the University of Texas at Austin J.B. Bird did offer remarks that avoided direct mention of Lions Municipal.

“Among the many gifts to the university, the 1910 bequest of land from George Brackenridge is one of the most enduring and generous,” Bird says. “As with all gifts entrusted to us, we will continue to strive to be good stewards of the Brackenridge land for the benefit of the current and future generations of students we serve.”

Crenshaw reports strong community support for SaveMuny.com and hopes this long-standing tension is close to resolution for more reasons than simply saving a historically significant golf course.

“This is a recreational green space less than 2 miles from downtown visited by more than 100,000 golfers and non-golfers,” he says.

Lions Municipal isn’t the only public course under threat from today’s political climate. In January, California state government revisited Bill AB672—legislation proposed by Rep. Cristina Garcia (D-Bell Gardens) to close the state’s municipal golf courses to transform them into open spaces to house the homeless. That legislation was slowed in committee as of late January, but it sets the tone for how many legislators and community leaders view city-owned golf courses. And attacks on affordable public golf courses can remove opportunities for underprivileged players from urban minority communities to learn and play the game.

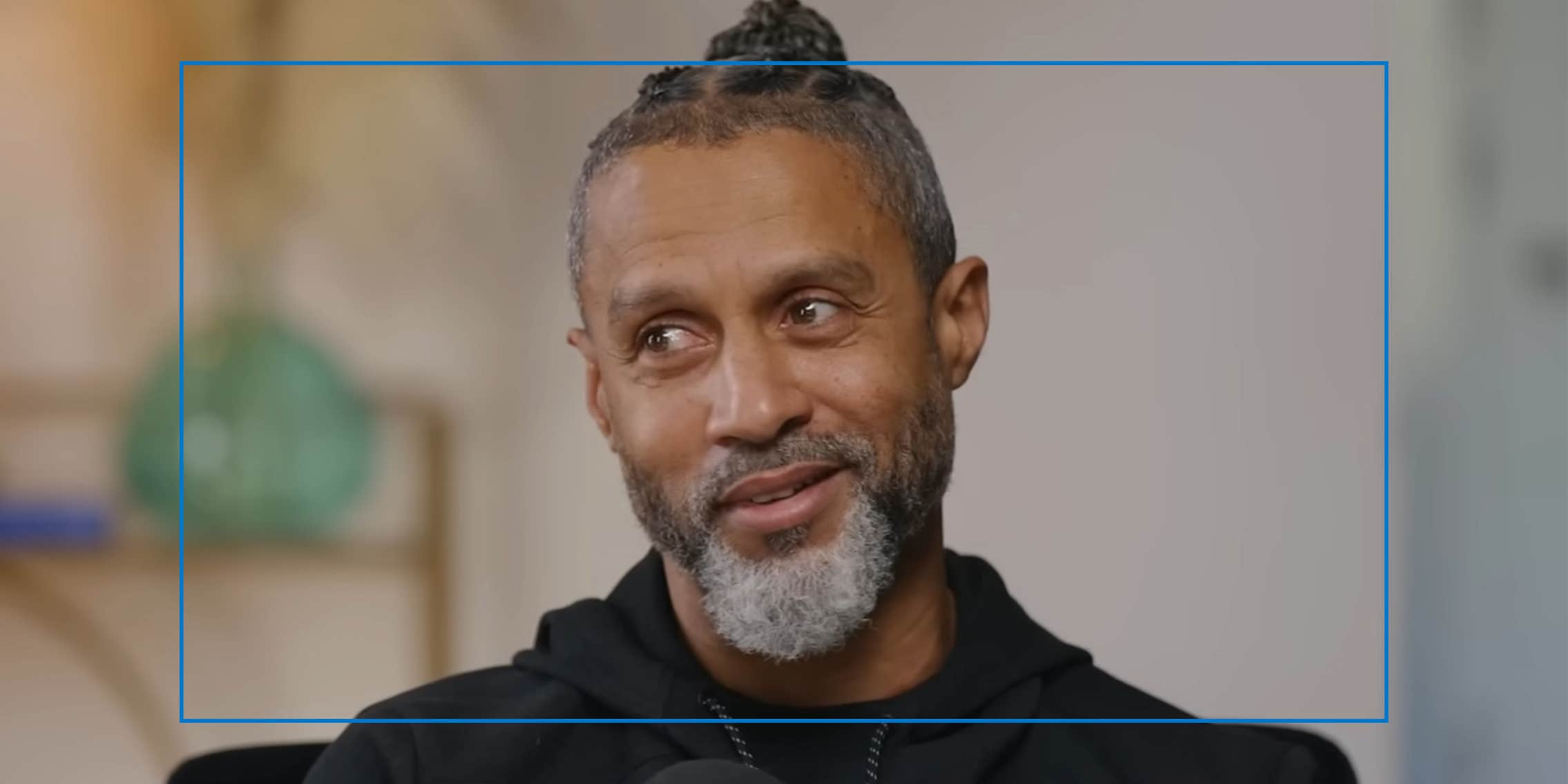

Ken Bentley is CEO of the Advocates Pro Golf Association Tour, a non-profit organization with the mission to bring greater diversity to the game of golf. The APGA Tour Board operates player development programs and mentoring efforts for inner city young people. He already has concerns that minority communities are less likely to try golf because the game is too expensive to play, considering the cost of equipment and greens fees—and closing municipal golf courses won’t help matters.

“We need golf to look like America,” Bentley says. “We need to make the game welcoming and affordable to more players on more courses, not fewer.”

Bentley highlighted an ongoing effort to create entryways into the game for African-American youth as minority-centric First Tee, United Golfers Association, and Youth on Course partner to allow all juniors between 6 and 18 years old to play golf rounds for $5 or less on more than 1,200 courses across the U.S. Most of those courses fall under the muny banner.

Bentley and the PGA reports that more than half of the young people brought into the game by First Tee in 2021 were non-Caucasian. And First Tee is expanding its reach to more low-income Title 1 schools and into underserved urban communities.

Since private courses and country clubs are often a good distance from these targeted economically challenged communities, the city or county-owned municipal courses often host efforts to bring African-American kids to tee boxes.

A champion of the game for the privileged and the common citizen alike, Robert Trent Jones, Jr. designed and built more than 270 courses in more than 40 countries on every continent except Antarctica. The enthusiastic architect of bucket list golf destinations such as the Makai Golf Course Princeville, Chamber’s Bay, University Ridge, the Founders Club, and the Links at Spanish Bay, he stays involved with real-world and online efforts to preserve public golf.

Jones insists that any concept of municipal courses being a drag on any community in general is nonsense. He sees munis as essential in bringing men and women of all ages and ethnicities together.

“When the game of golf was conceived, both pauper and prince played it together,” Jones says. “It’s a game that knows no social boundaries, whether it’s at some of the most elite courses in the world or at your local municipal. Even St. Andrews itself—the home of the game—is a municipal golf course.”

Jones reminds anyone who doubts the value of a muny that such a facility is created and maintained by and for taxpayers as a valued resource.

“At the end of the day, a golf course is a park—and a park serves as the lungs of its community,” he says.

Back in Texas, Crenshaw realizes the battle at SaveMuny.com hinges largely on Austin’s economic realities.

“While the City of Austin is aware of the historical significance of the course, money is a factor for them, as well,” he says. “But, great cities save their great spaces, and we’re hoping Austin uses their leverage and steps up to save the course.”

ESPN+ celebrates Black stories.

Stream the Black History Always Collection.

See more stories from Presser – examining the intersection of race and sports online.