No one expects to get cancer. Sure, you might have the “what if” moments, but you never actually think it’s going to happen. Until it does.

I was diagnosed with testicular cancer on Aug. 8, 2012. Two days later, I had surgery to remove the tumor; less than month after that, I started chemo. I had just turned 30 years old.

So much of our lives are shared on the Internet. Mine is no different. Even before I was diagnosed, I shared my work, mundane details about my life, dating—the essentials for a man in his 20s living in New York at the time. So when cancer showed its fugly face, I had to document it.

I’ve written a lot about my cancer, but I’ve never actually showed it. If our virtual footprints are a window into even a little piece of the person we truly are, then this is the virtual story of my cancer.

Pre-diagnosis

I’ve never been one to care about age. Turning 30 was just another birthday. If anything, it marked a change in a decade and reflected the direction I wanted my life to go in, more professional—hopefully personally fulfilling.

The pain started at the end of July, shortly after my birthday. Having just arrived in Los Angeles from New York, I didn’t have a doctor. I went to my friend’s doctor, which led to another doctor, and then another. The entire time I was cracking jokes. I wasn’t taking it seriously, yet deep down I knew something wasn’t right.

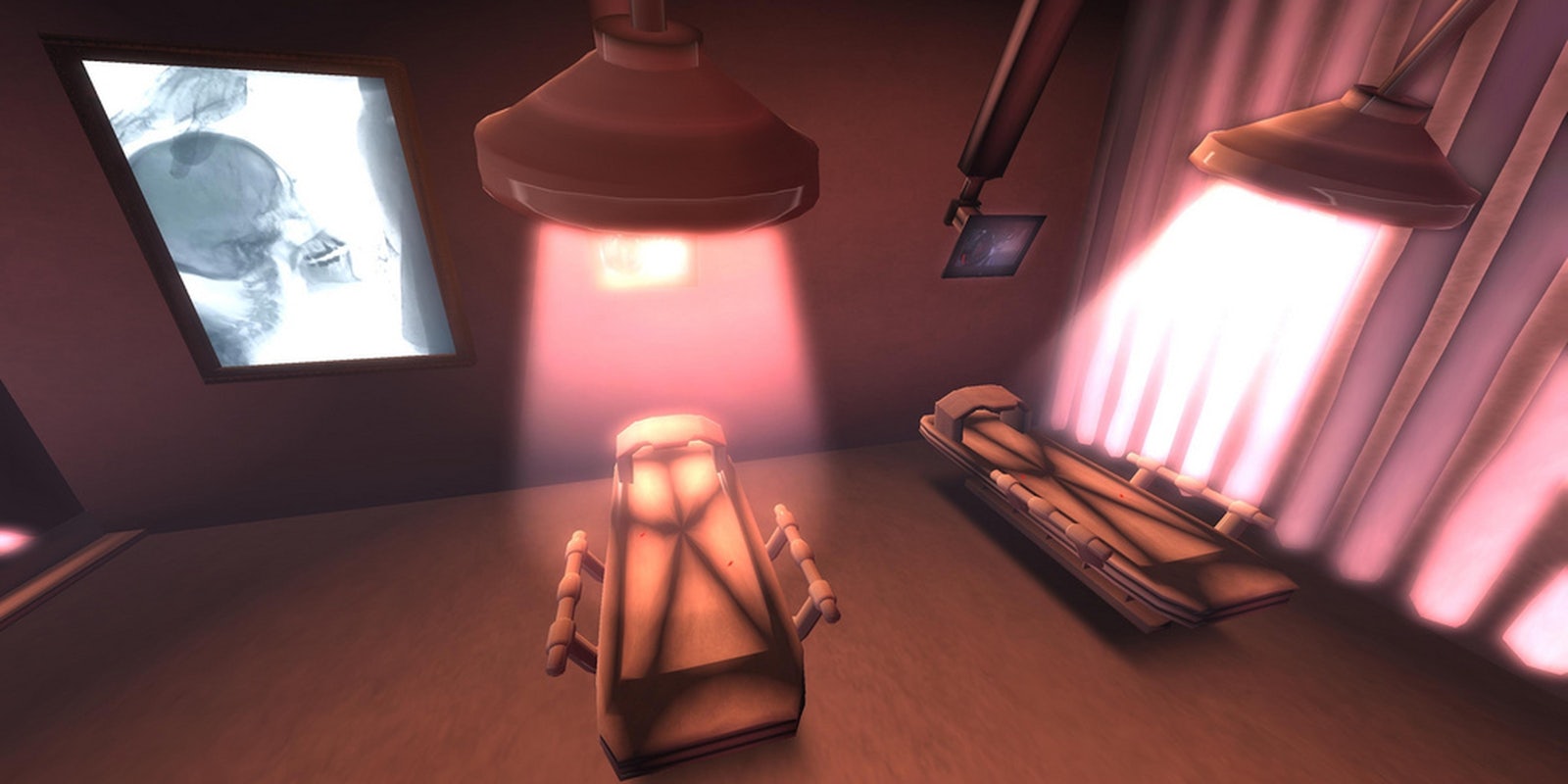

Surgery

The surgery happened less than 48 hours after the urologist discovered the tumor. I tried to make it funny, to keep up a good spirit, but deep down I was terrified about what it all meant. I didn’t know what was going to come after the surgery, and it scared the shit out of me.

Which, coincidentally, was what I focused on to get through the surgery. Instead of fearing death or side effects, I was concerned about shitting on the operating table. The nurses and doctors reassured me, but it wasn’t enough. I woke up from surgery drugged, groggy, and convinced they were judging me.

Pre-chemo

There’s no one way to prepare for chemo. The biggest decision I had was where to do it: Los Angeles, New York, or in St. Louis, where my family lives. I ruled New York out immediately; there was no way I was doing chemo and then taking the subway. I considered St. Louis seriously, and also considered how hurt my family would be if I chose Los Angeles, fearing they’d take it as a rejection. In the end, though, I decided to stay in L.A., where most of my life is based, in order to maintain some independence and normalcy. To this day, I still feel guilty about this decision, but I know it was for the best.

There’s a chemo class that breaks down exactly what’s going to happen to you. Mine was led by an annoying nurse practitioner that kept a feather tied in her hair. As she spoke to me (or rather, down to me), I imagined the feather magically transforming, Harry Potter–style, into a bird that would poke her eyes out. My reaction to this nurse was just a precursor to how I would respond to the rest of the medical community in the very near future.

I didn’t want to seriously think about having kids, so on the strong suggestion from mother, I decided to freeze my sperm. I’m glad I did; chemo officially killed my chance at having children. Just another thing cancer takes.

Chemo

Describing chemo is like trying to remember every detail of a dream. It’s foggy, but you know things happened.

Everyday is different, yet also exactly the same. You feel new things at every moment, yet everything around you is happening just as it did the day before. The nausea feels new, but it was there yesterday, too.

When people ask me what chemo was like, I say, “Imagine being sleepy and hungry all the time, but never able to sleep or keep food down. Then make that last for months.”

Nurses would talk to me about things that I didn’t care about, doctors would attempt to get to know me, secretaries would act as if they remembered me, yet all I wanted was to be left alone. I said this often, but it rarely sank in. It was almost like being in prison. Another inmate/patient across the room would visually acknowledge how annoyed I was as the nurse told me about her kid, for the fourth time that day. I did time, man, and all I wanted to do was escape.

I still attempted to live a somewhat normal life. I wasn’t working because of my chemo schedule (five days a week, six hours a day), but I stayed busy. For example, I rested about four to five times a day. Watched a ton of movies. Wrote all the time. Even made time for Halloween, a personal favorite gay holiday.

Side effects

You’d think you could hop right back into your life post-chemo, but that’s not the case. I tried, don’t get me wrong, but in the end I failed miserably.

Let’s start with the teeth. Pre-chemo, I had to have a few teeth removed because of possible infection during chemo. So as soon as I could I started the process of getting teeth put back in. As you’ll see, it wasn’t as easy as screwing it in (nor as cheap).

I also went back to work. I made it three months at the job before my breakdown. I cried every day, wouldn’t eat, avoided friends, had frequent panic attacks. Eventually I was diagnosed with PTSD. I left work and went back to treatment, this time for my brain.

I needed to feel, truly feel, what had happened to me. My life was completely uprooted, before I had a chance to even ask questions I was getting cut open, then filled with poison. How was I supposed to process all that?

Another factor was my relationship status. Even though I had friends and family around me, I’m single, and didn’t have anyone to intimately share the experience with, someone to emotionally release the things that I was feeling. Instead I bottled them up, until I couldn’t deny them anymore.

Getting back to me

After a lot of therapy and a regular dose of anti-depressants, I slowly began getting back to a life. I say “a life” and not “my life” because I don’t know what the latter terms means anymore. I don’t want to go back to the person I was at the beginning of this piece, the freshly 30-year-old with dreams. Something big happened to me and changed everything, I needed to acknowledge that.

I got back to writing, performing, socializing. It was rough and continues to be a struggle, but I’m making it happen. Honestly, it’s exciting.

Now

The biggest question people ask me now is, “So are you in remission?” That’s probably the hardest question for somebody with cancer to answer. I’m not receiving the treatment I once did, but I’m being monitored. I won’t be declared free of cancer until five years have passed. If nothing pops up before then, then I’ll be in remission. But because I have hair and look healthy, this isn’t what people want to hear.

Fortunately, it’s not about what people want to hear. Cancer isn’t about making others feel good about their own mortality or outlook on like, it’s a thing, a chemical thing that happens to people. It’s not a fight, or a struggle, or a battle, there are no winners and losers. Some live, some die. Those that die didn’t lose, or give up, or God forgot about them, it’s just the cancer was too much and it killed them. Literally killed them.

Am I a survivor? Well yeah, but so are you. Everyone is. The fact that you’re alive means you’ve survived. Guess what? That’s it. The meaning to all of this. It’s about living, being alive, right now, in this moment. We’re all survivors.

H. Alan Scott is a writer/comedian based in New York City and Los Angeles. His work has been featured on the Huffington Post, Thought Catalog, OUT, xoJane, The Advocate, MTV, Logo, WitStream and Time Out. He really wants you to follow him on Twitter at @HAlanScott.

Photo via Torley/Flickr (CC BY S.A.-2.0)