After comedian Robin Williams committed suicide two weeks ago, fans took to the Internet to express their grief, as well as their admiration for his work. Whenever a beloved celebrity passes away, regardless of the cause, social media temporarily becomes a sort of memorial to that person, a chronicle of the ways in which they changed lives.

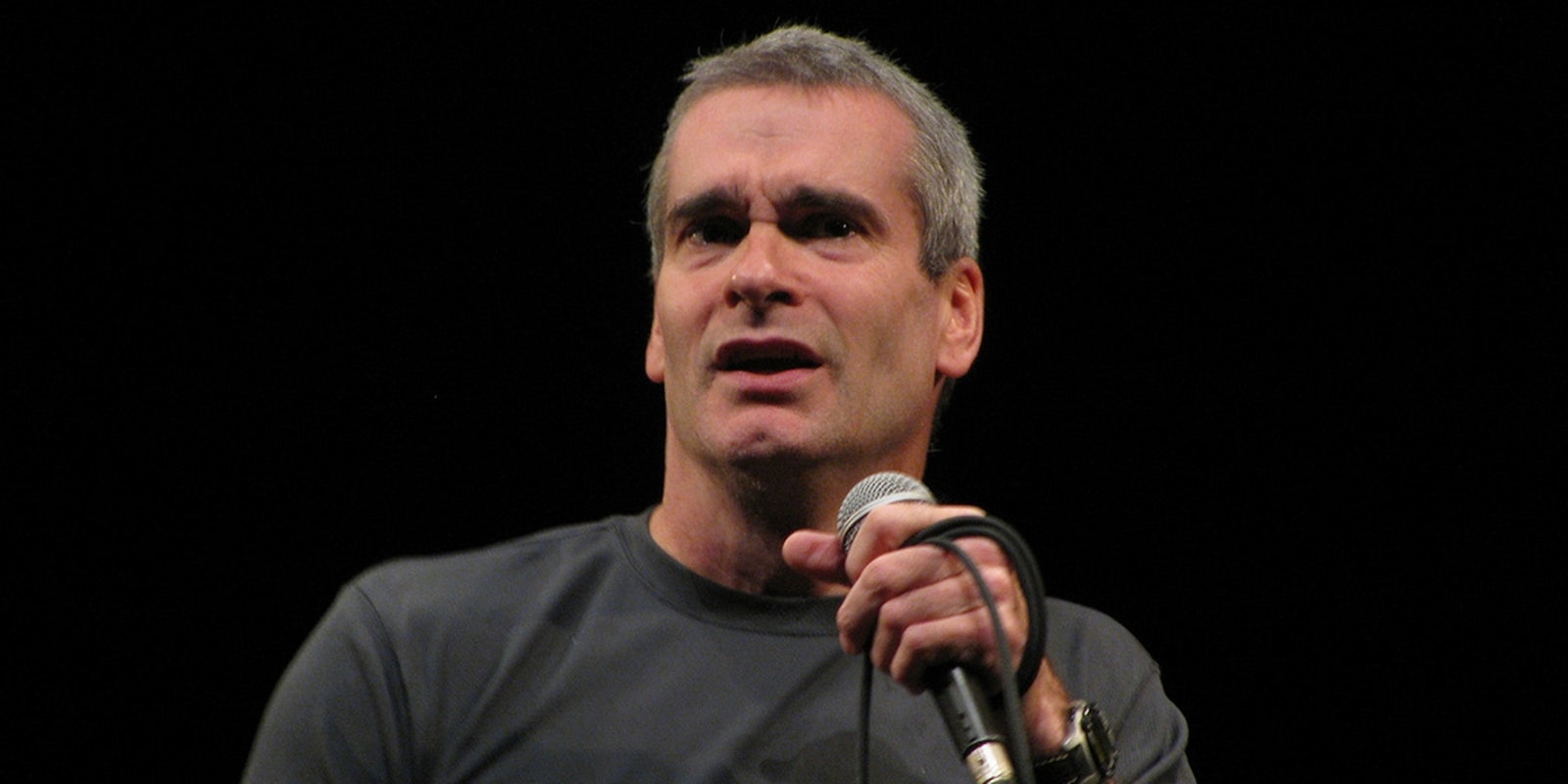

However, when the cause is suicide, a celebrity’s death also brings out lots of dismissive, inaccurate, or even hateful statements about people with mental illnesses. According to some, Williams was “cowardly” and “selfish” for committing suicide. Last week, Musician Henry Rollins wrote an op-ed for L.A. Weekly (for which he apologized over the weekend) in which he said that he views people who commit suicide with “disdain,” claiming that Williams traumatized his children. There was plenty of rhetoric about suicide being a “choice,” the implication being that it’s the wrong choice.

Comments like these not only misinform people about the nature of mental illness, but they are also extremely hurtful to those who struggle with it. As the Internet continues to respond to Robin Williams’ death, here are some suggestions for a better conversation about mental illness and suicide.

1) Do your research.

We all have a “folk” understanding of psychology, which means that we experience our own thoughts and feelings, interact with other people, and thus form our opinions on psychology. Obviously, noticing things about ourselves and the people around us can be an important source of knowledge about how humans work.

But it’s not enough. If you haven’t had a mental illness, you can’t really understand what it’s like to have one—unless you do your research. Depression isn’t like feeling really sad. Anxiety isn’t like feeling worried. Eating disorders aren’t like being concerned about how many calories you consume. Your own experiences may not be enough.

Before you form strong opinions about mental illness and suicide, you need to know what mental illnesses are actually like, what their symptoms are, what treatment is like, what sorts of difficulties people may have in accessing treatment or making it work for them. If you can make tweets and Facebook statuses about a celebrity’s suicide, you can also do a Google search. Wikipedia, for all its drawbacks, is a great place to start. So are books like The Noonday Demon and Listening to Prozac.

2) Never engage in armchair diagnosis.

Now that you have a good idea of what different mental illnesses look like, you should try to figure out who has which ones, right?

No, please don’t. Armchair diagnosis, which is when people who are not trained to administer psychiatric diagnoses try to do so anyway, is harmful for all sorts of reasons that Daily Dot contributor s.e. smith describes in a piece for smith’s personal blog:

The thing about armchair diagnosis is that it mutates. First it’s a ‘friend’ deciding that someone must have bipolar disorder because of some event or another. Over time, that’s mutated into an ‘actual’ diagnosis, repeated as fact and accepted. Everyone tiptoes around or gives someone sidelong glances and makes sure to tell other people. Meanwhile, someone is completely puzzled that other people are treating her like she’s, well. Crazy.

Whether the person you’re talking about is a celebrity or not, it is up to them whether or not to make public any information about their health. Mental health is part of health. While having a mental illness should never be stigmatized, unfortunately, it still is. People deserve to decide for themselves whether or not they are willing to disclose any mental illnesses they may have.

Even if someone commits suicide, that doesn’t mean we can come to any conclusions on which mental illness they had or didn’t have. First of all, not everyone who commits suicide could have been diagnosed with any mental illness just prior to it. Second, various mental illnesses may lead to suicide. Many online commentators, including journalists, simply assumed that Williams had depression. However, he may have also had bipolar disorder, in which depressive episodes are interspersed with manic ones. Williams himself never stated which diagnoses he had, so it’s best not to assume. Whatever he had or didn’t have, it is clear that he was suffering.

3) Remember that mental health is an issue of health, not morality.

A lot of the comments made about Robin Williams and other people who attempt or commit suicide have more to do with perceived morality than anything else. “Selfish,” “cowardly,” “weak”—these are all moral judgments. Author Jenny Trout illustrates how odd such comments would sound if made about any other type of illness:

If we’re going to throw out platitudes like ‘suicide never solves anything’ or ‘if he had only waited a day, things might have gotten better’ when someone dies from suicide, then we need to say the same things about people who die from other diseases. ‘He shouldn’t have died from heart disease. If he’d waited a day, things might have gotten better.’ ‘Having a stroke never solves anything.’ ‘Dying from cancer is the most selfish thing a person can do.’ We often blame patients for their illnesses, especially in cases where addiction, obesity, or sexuality is a factor, but somehow it strikes me as especially cruel in a case where the criticism is echoing the very thing that killed the patient in the first place. People who have committed suicide already believe themselves selfish, weak, and cowardly. Rarely does a person succumb to Leukemia specifically because they feel bad about what a Leukemia-having person they secretly are at heart.

Like many other illnesses, depression and bipolar disorder can be fatal. When that happens, it’s unquestionably a tragedy, and, like other potentially fatal illnesses, it is sometimes preventable. But part of the horror of mental illness is that its symptoms often make seeking help difficult or even impossible. This has nothing to do with the “strength” or “bravery” of the affected person. It is a terrible thing that can happen, and we should fight it, not by shaming and denigrating people with mental illnesses, but by advocating for more accessible, more effective treatment.

4) Avoid assigning blame.

Virtually none of us has an easy time dealing with the fact that sometimes terrible things happen to good people seemingly at random. Mental illness and suicide is no exception. That may be why it’s so tempting to assign blame when someone commits suicide—if not on the person who died, then on their family who didn’t urge them to get treatment, or their partner who didn’t love them enough, or their friends who weren’t supportive enough, or their therapist who wasn’t good enough, or their psychiatrist who prescribed them a medication that didn’t work.

Blaming people is tempting and understandable, but it isn’t helpful. Sometimes, even the most loving spouse or the most supportive friends or the most talented therapist can’t help someone. Sometimes family members don’t know enough about mental illness to know that they need to urge someone to seek treatment. Sometimes the psychiatrist prescribes a medication that worked for everyone else they’ve prescribed it to who had similar symptoms, but this time it just doesn’t and we don’t know why. It sucks, but sometimes it’s nobody’s fault.

5) Privilege the voices of those who have experienced mental illness most directly.

I’m not the only one who’s noticed that people are often more willing to listen to—and to talk to—the friends and family members of those with mental illnesses, rather than the people with the mental illnesses themselves. I get it. It’s often uncomfortable to be exposed to the perspective of someone who is battling mental illness. The things they say don’t always make sense unless you already understand mental illness fairly well.

People who are close to those with mental illnesses have important things to say, as well as their own needs that we should address. Mental health professionals, too, have valuable knowledge and experience. But if you want to understand what mental illness feels like and how it affects the lives of those who have it, you need to listen to those who have it.

In practice, this means that online conversations about mental illness should never ignore those who actually deal with it on a constant basis. If you’ve never experienced mental illness and you find yourself in an argument about it with someone who has, it’s probably a good idea to listen more than you speak.

6) However, keep in mind that everyone’s experience of mental illness is different.

One unfortunate thing I noticed a lot in the wake of Robin Williams’ suicide is people saying things like, “Well, I was depressed too, but I didn’t kill myself.” The implication being, of course, that they are somehow superior to Williams because of it.

Mental illnesses vary in severity even if the diagnosis is the same, and they also vary in their responses to treatment. Unlike many others who suffer from mental illness, Williams would have had access to all the therapists and medications he wanted. While it is unclear whether or not he took advantage of that access, a small minority of people with mood disorders like depression are not responsive to any treatments.

People with mental illnesses cannot necessarily speak for others with mental illnesses, even if it’s the same diagnosis. The fact that other people experience depression or bipolar disorder and do not commit suicide does not make Williams any more “weak” or “selfish.” We cannot know how it looked from where he was. We do know, though, that mental illness can skew someone’s perception so severely that it feels impossible for them to continue living.

Psychiatry and mental health care are still in their infancy as fields of medicine. It is my hope that, years or decades from now, we will look at tragedies like Williams’ death and wish we could somehow send our newfound knowledge back in time. For now, we can help by arming ourselves with the best science currently available, pushing back against stigmatizing behavior like calling suicidal people “selfish,” and discussing these issues with a little more compassion. Yes, even though it’s the internet.