By our third phone call, Steven Lloyd Sadler was a fugitive.

Facing federal charges for drug trafficking and distribution, Sadler decided he’d rather skip the trial and jail sentence altogether. He was pulling away from Seattle, where he was charged, and we talked for hours. He began that particular conversation on speakerphone, attempting to circumvent the state’s law prohibiting the use of cellphones while driving, but noisy interference forced him to pick up the call.

He shrugged as he put his phone to his ear, his other hand taking a firm grip on the wheel.

“I hope I don’t get pulled over.”

I’d spent hours talking to Sadler, one of Silk Road’s most popular heroin and cocaine dealers, before and after he made the decision to run. By late October, he was out on bond, seemingly as a reward for helping Homeland Security in a larger investigation into the infamous Deep Web black market.

The conditions of the bond were clear: Sadler wasn’t allowed leave the state of Washington. He was also strictly forbidden from dealing or using drugs.

“Hold on,” he cut in at one point. “I have to buy some cocaine, can I call you back?”

Five minutes later, he was back on the line, as chatty as ever.

At the time, there was no clear direction forward. Maybe he’d go to Las Vegas on a wild bender. Maybe he’d try to start his drug empire over in Los Angeles. Maybe he’d visit old friends in his hometown who didn’t know about his criminal enterprise.

Sadler talked through each potential scenario, as if working through them in his mind, looking for possibilities and pitfalls. In roughly 10 hours of phone calls over the course of several weeks, Sadler told me almost everything.

Then he dropped off the grid.

“I’m guilty,” Sadler admitted in our first conversation, several weeks after he was let out on bond.

Sadler was apprehended by Homeland Security on July 31, 2013, when 20 federal agents descended on his condo. Officers accused Sadler and his girlfriend, Jenna White, of running one of the most successful illegal drug operations in Silk Road history, aided by the veil of Tor‘s anonymizing software. Under the alias Nod, he ran the digital storefront: taking orders, making the all-important supply connections, and coordinating shipping. White, 20, reportedly handled much of the driving and mailing. A third person, who has thus far escaped prosecution, Sadler said, helped with operations.

The trio sold premium product, and a lot of it: 2,269.5 grams of cocaine, 593 grams of heroin, and 105 grams of meth in four months, according to the criminal complaint, but all signs point to a much larger operation.

The trio sold premium product, and a lot of it: 2,269.5 grams of cocaine, 593 grams of heroin, and 105 grams of meth in four months, according to the criminal complaint, but all signs point to a much larger operation.

For two months, Sadler served as a valuable federal informant against Silk Road and its founder, Dread Pirate Roberts. After he was finally arrested and taken before a judge in October, his name was plastered across the media landscape, as was his role as an informant.

Shortly after we published our extensive Oct. 9 story on Nod’s rise and fall, someone purporting to be Sadler sent me an email saying it “brought a smile to my face.” He wanted to tell his side of the story while he still could.

Within minutes, Sadler sent a photograph of his Washington driver’s license to confirm his identity. That was followed by court documents, including the discovery and evidence log, the search-and-seizure warrant, and access to hundreds of emails between Sadler and federal authorities from his time as a criminal informant.

Our conversations lasted hours. The first time we spoke, he was regularly interrupted by a friend pleading with him to shut up. Sadler laughed it off. He was facing a potential life sentence. What did he have to lose?

A warrant was reportedly issued for his arrest on Nov. 6, a week after he left his hometown of Bellevue, Wash.

“They’ll be pretty pissed off at me,” he said, referring to his federal public defenders.

In a strangely cheerful tone, at odds with the severity of his comments, Sadler told me how he lost almost everything: his freedom, his business, and his girlfriend. Sadler and White, who are facing the same charges, are now forbidden to speak to each other. They hear about the other only indirectly, through mutual friends.

Worse still, the reputation he spent years building on the Web has been tarred and feathered, his legacy reduced to that of a cheap crook and snitch.

“I don’t like the way society treated me as a bad person,” he said. “That really bothered me.”

“I excluded violence and cheating and all these things associated with people of that ilk,” he added. “I didn’t think people would have a negative impression of what I’d done.”

For the first 38 years of his life, Steven Sadler was drug-free.

As an information technology professional employed at big companies like Intelius across Seattle’s formidable tech sector, he’d worked in big data, information security, and systems administration for two decades.

By his 30s, though, Sadler said he had grown tired of the IT world—and his life. He laid much of the blame on his father, who impressed upon him the idea that possessions and money engender happiness. With Sadler’s six-figure income leaving him deeply dissatisfied, like Tyler Durden in Fight Club, drastic change was inevitable.

He found some solace in prostitutes, but “there’s no substance to that relationship,” Sadler said. “If there’s one regret in my life, it’s that I didn’t push more toward family bonds, real social connections, being less of a hermit.”

He found some solace in prostitutes, but “there’s no substance to that relationship,” Sadler said. “If there’s one regret in my life, it’s that I didn’t push more toward family bonds, real social connections, being less of a hermit.”

He tried pot. He liked it. Then he moved on to cocaine. After he heard about Silk Road on the tech community Slashdot, Sadler was soon buying drugs and befriending vendors online.

After a short time on the site, Sadler bought a costly vendor account from PaythePiper, an established Xanax salesman on Silk Road who wanted to retire, in an attempt to cash-in on the store’s positive reputation and customer base. Piper taught Sadler how to purchase pills from overseas and flip them for a profit on the black market, but the storefront didn’t last long. It’s against the rules to sell accounts, and Silk Road administrators shut it down after somehow learning about the transfer.

In May 2012, Sadler purchased his own vendor account, called Poundsign, and started buying supplies in bulk. For $1,000, he acquired 335 pills of Alprazolam (generic Xanax) from Pakistan. That’s about $3 per pill. He sold them for $6 each on Silk Road, a considerable markup on street prices. The profit was nice, but Sadler soon discovered that actually receiving his supply was the hardest part of the operation. Often, the pills would get lost in the mail or caught by customs. In November 2012, cops intercepted 900 tablets addressed to a post office box under the name Aaron Thompson. Police released the package, but no one came to retrieve it.

“I thought customs didn’t care,” Sadler recalled. “It turns out they do.”

He tried selling other pharmaceuticals, most notably Valium, but found demand was relatively weak. When shipping Xanax from overseas became too unsafe, Sadler decided to make the move to a surer product: heroin. He didn’t even use heroin when he began selling it, but he was able to buy the drug domestically.

Sadler created a new account to distinguish between his two operations. Overnight, he reinvented himself as Nod, a heroin kingpin.

Nod’s specialty was “bitchin’” black-tar heroin, as he put it in his pitch to customers.

To kickstart business, Sadler made 10 purchases from Nod and left himself positive feedback. He sold high-quality heroin at low prices to create hype. It wasn’t immediately profitable, but he was focused on the long-term potential. The customers who liked his stuff zealously went to bat for him, praising everything about his operation with equivalent of five-star Yelp ratings on everything from shipping and customer service to, of course, the heroin itself.

From the moment he became a vendor on Silk Road, Sadler was selling a premium product. As Poundsign, he was renowned for customer service. As Nod, he was likely the most reliable high-quality dope slinger around. He could afford to be.

Sadler bought a gram of black-tar heroin for $50. He sold it for about $220, a 440 percent markup.

Black-tar heroin. Photo via the Drug Enforcement Agency

“With heroin, you just get shit once in a while,” Sadler said. “You’re stuck with it.” While other dealers had no problem selling lower-quality drugs, Nod made a point not to—choosing to absorb the loss—and customers responded in kind.

“Silk Road was a value-added portal,” Sadler said. In essence, people were paying for the drugs but more so for peace of mind and quality. They wanted to avoid trouble, to find someone reliable.

“These people are typically professionals in the 30- to 40-year-old range,” Sadler confided. “They want to be treated with respect.”

“These people are typically professionals in the 30- to 40-year-old range,” Sadler confided. “They want to be treated with respect.”

Nod’s heroin “tastes delicious,” Nod’s first real customer wrote, “and still retains its potency and the initial surge of vinegar on the inhale but once its in your mouth/lungs for a second it just tastes very sweet.”

Nod’s reviews were so good that he was accused of faking them. (He did, of course, make earlier purchases from himself, but posting phony reviews on the forums—as with eBay or Amazon—is seen as a much worse offense by most Silk Roaders.) To boot, he learned how to game the system with some some sleight-of-hand editing. For example, he’d create a listing for one gram of cheap, top-notch heroin, and then sell it in high volume so it’d rise through the ranks. When it reached the top, he’d update the listing to push even larger, more expensive quantities.

All of a sudden, big bricks of Nod’s finest product were at the top of Silk Road with a ton of great reviews, selling like mad.

By December 2012, Sadler’s year-old operation was having major problems. Police had intercepted a number of his packages, and he had lost his cocaine connection—a dealer apparently ripped him off for thousands of dollars—leaving him unable to meet his customer’s demands.

“Losing the money is a problem but not a big deal,” Sadler said. “Losing the connection is what really hurts.”

Much to the disappointment of his clientele, Sadler took a noticeable break as he searched for a new supply line. Later that month, Sadler spoke with another Silk Road cocaine vendor named Magic Moments. Nod proposed a partnership in which he handled marketing and sales while Magic used his functioning supply chain to ship cocaine to his customers.

“It didn’t go through because he had the ethics and organization of a street dealer,” he said. “He couldn’t see past his face.” Magic, Sadler claims, ended up ripping another Silk Roader off for about $7,000.

“It didn’t go through because he had the ethics and organization of a street dealer,” he said. “He couldn’t see past his face.” Magic, Sadler claims, ended up ripping another Silk Roader off for about $7,000.

Still, Sadler was convinced that working with fellow Silk Road vendors was the key to maximizing his success. He found a new connection in Los Angeles, a man some believe to be Michael Shapiro, a 28-year-old from California. While extent of their relationship remains unclear, Sadler confirmed to me what court documents had said: Shapiro was the intended recipient of an intercepted shipment of $3,200 in September 2012.

Sadler spent most of January 2013 in Los Angeles getting set up to sell hard drugs. By February, he was turning $105,000 monthly in profit, mostly off of cocaine, a drug with an enormous customer base on Silk Road, but it came at a steep price.

Sadler’s attempts to collaborate only worked on paper. After all, he ran a great marketing operation and was selling premium product. If he could collude with other cocaine dealers to set prices even higher, he saw no reason why more profits wouldn’t follow.

His messages to other cocaine dealers quickly leaked to the public, causing ire with sellers and buyers alike.

“There’s a ton more money to be made cooperating than by competing,” Nod wrote in the leaked documents. “Let’s help each other get rich!”

Dread Pirate Roberts, the leader of Silk Road, quieted the controversy. It was impossible to create a cartel on a truly free market in any case, Roberts said, a truth Nod realized as his potential collaborators leaked his offers and continued to try to undercut his prices.

“I thought I was on to something,” Sadler reflected. “I made a list; it got a little over the top. I had a lot of good ideas and I was trying to throw out anything. I was brainstorming. It didn’t go well.”

He paused.

“But it didn’t hurt sales at all.”

As anyone who’s ever seen Breaking Bad can attest, pushing drugs is only half the equation. You still have to launder the profits.

Silk Road runs on Bitcoin, a digital cryptocurrency popularized by the Deep Web for its anonymous nature. It’s traded like gold, with a fluctuating market value. Some people use tumblers to obscure the transaction chain, making Bitcoin “as anonymous and private as cash,” the Electronic Frontier Foundation once proclaimed.

But Sadler still needed a way to transfer his influx of bitcoins into cash without linking it to his bank account.

First, he stole identities. From his work at Intelius, a public records business, Sadler said he had access to social security numbers, drivers’ license numbers, mothers’ maiden names, and other information that, when combined, could be used to set up prepaid credit cards in the names of other people. To lessen risk, Sadler targeted Poland, which essentially doesn’t require a real individual to open prepaid cards. An unidentified Polish man sold Sadler, he claims, more than 120 Polish bank debit cards.

First, he stole identities. From his work at Intelius, a public records business, Sadler said he had access to social security numbers, drivers’ license numbers, mothers’ maiden names, and other information that, when combined, could be used to set up prepaid credit cards in the names of other people. To lessen risk, Sadler targeted Poland, which essentially doesn’t require a real individual to open prepaid cards. An unidentified Polish man sold Sadler, he claims, more than 120 Polish bank debit cards.

The process went something like this: Sadler would convert his bitcoins to fiat currency and deposit them into his prepaid cards. He’d then withdraw the money from 20 different cards at a time at walk-up ATMs. With this method, cashing out cost 14 percent in fees and 20 percent more in man hours to complete the process from start to finish.

“120 cards is a ridiculous amount of labor,” Sadler said. It was so bad that in September 2012, he almost quit the business entirely.

Soon, Sadler stumbled on an alternative. A personal friend of Sadler’s wanted to buy bitcoins to purchase MDMA on Silk Road. She offered $12,000 in cash. There were no fees to worry about. Transferring coins this way was obviously a much preferred situation. From there Sadler found LocalBitcoins.com, a website that connects Bitcoin traders and buyers—either in person or online—for a low fee.

The site moves quickly. Within a few seconds of joining the service’s chat room, users are typically bombarded with messages asking if they are selling bitcoins. To avoid fees and legal issues, bitcoins are sold for less than market value, which helps traders use the site to to make a living. It’s a popular service in tech-friendly cities like San Francisco.

“Any Silk Road vendor not on LocalBitcoins is losing a lot of money,” Sadler said.

Soon Sadler was doing $8,000 deals out of a suitcase in a local Starbucks. When he outgrew the local market, he found a new LocalBitcoins buyer in Las Vegas: Mark Russell, a preacher and student of the Reformed Theological Seminary. Russell, who remains an active buyer on LocalBitcoins but could not be reached for comment, requires a minimum order of $5,000, with a fee starting at 5 percent.

Russell and Sadler first began trading in January 2013, Sadler said, with small trades in Las Vegas casinos. While Sadler said that some traders were “car salesmen, slimeballs who will do anything to pull one over on you,” he described Russell as polite, intelligent, and honest. Sadler said he made his biggest ever single trade when Russell gave him $84,000 in a briefcase in the bar of the Cosmopolitan casino, a spot chosen for its security. After all, no one is going to run out of a casino holding cash without being stopped.

Sadler claimed he was eventually making $70,000 per month on cocaine alone at Silk Road.

Sadler wasn’t satisfied. He was creating something resembling an empire, ensuring his legacy.

“I could have done more,” he said, “with a better work ethic or more motivation.”

Simple mistakes and poor timing sealed Sadler’s fate.

His partner and then-girlfriend, Jenna White, took sealed product packages to dozens of post offices around the Seattle area as a security precaution. After authorities intercepted packages in September 2012, post office clerks were able to identify White as the blonde woman responsible for them. She bought an unusually large volume of stamps and her handwriting was identical to that found on the packages containing heroin caught by police, according to the complaint. She parked directly in front of cameras at post offices, making it easy for authorities to identify her face, car, and license plate number.

White and Sadler, lovers separated by a 20-year age gap, became business partners in a highly profitable, highly risky drug operation out of their condo. At White’s determined insistence, Sadler said he gave her more and more responsibility in the operation. The relationship turned toxic, as the mixing business and pleasure often does.

The couple broke up on July 29. Soon, White was carrying boxes of her belongings out of the condo they shared. What neither knew at the time was that the cops were already watching closely. When police saw White on the move, they assumed the couple was making a run and obtained a warrant. They were arrested two days later.

The couple broke up on July 29. Soon, White was carrying boxes of her belongings out of the condo they shared. What neither knew at the time was that the cops were already watching closely. When police saw White on the move, they assumed the couple was making a run and obtained a warrant. They were arrested two days later.

Homeland Security, however, had its sights on a much bigger target: Dread Pirate Roberts. A few hours after he was first arrested, the agency asked Sadler to become an informant.

“No,” he quickly responded, “of course not.”

Then agents searched his home and found drugs, supplies, and well-kept records that Sadler thought might remain hidden. The drugs, according to the evidence log, were stashed in the ceiling, next to various paraphernalia and documents.

“I didn’t think they’d find all the drugs,” he told me. “They did, and I was fucked.”

It didn’t take long for Sadler to flip. Agents said that if he cooperated, they’d leave the criminal complaint against him sealed so that no information would be made public. Soon, he was officially cooperating with Homeland Security, using his acclaim as a vendor on Silk Road and a friendly relationship with Roberts to help track down the founder of the Internet’s most notorious black market.

“It was interesting,” Sadler said. “People always talk on Silk Road about how to find the servers, and this was my chance to do it. It sounded like fun, and it would affect someone I didn’t have a problem with harming.”

Sadler’s job was to send a constant stream of carefully crafted messages to Roberts to work his way into the founder’s confidence. The ultimate goal was to administer a Silk Road server or, using a staff position, to find a financial trail to follow.

This wasn’t the first time Sadler and Roberts considered working together. Early in 2013, months before any law enforcement became involved, Sadler offered to help Silk Road deal with its considerable growing pains. The site had dealt with a week of downtime following a nasty distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack, and Sadler had some ideas that he thought could help Silk Road. No deal transpired, but the line of communications had been established.

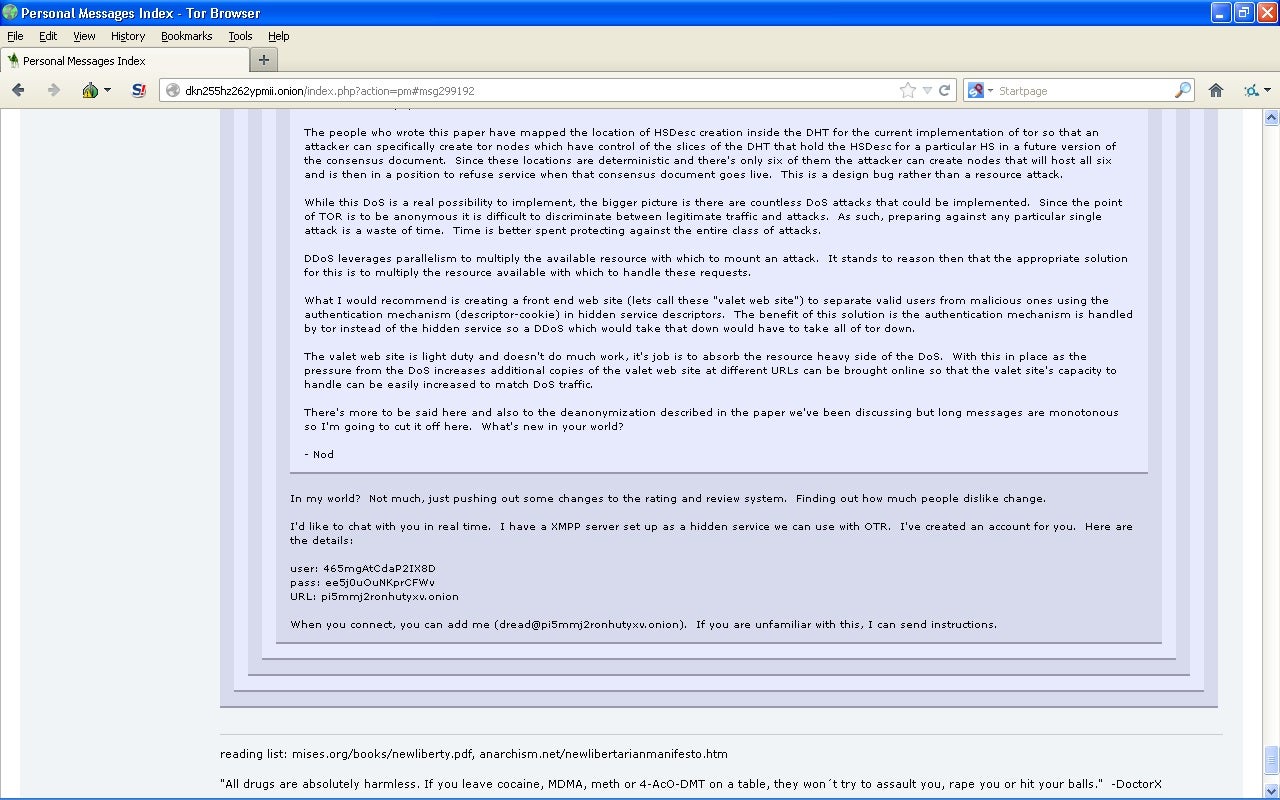

Homeland Security wanted more than talk. Sadler, overseen by federal agents, began regularly communicating with Roberts about Silk Road’s security and scalability issues. In particular, Roberts was concerned about vulnerabilities described in a 2013 research paper, called “Trawling for Tor Hidden Services,” which claimed a hypothetical attack on Tor that could de-anonymize a service in eight months. Sadler said the police believed it would take four months of computing power. He thought it could be done in even less.

Through police intermediaries, Nod and Roberts allegedly discussed Silk Road’s security at length.

In his early correspondence with law enforcement, Sadler laid out what he thought of Roberts.

“DPR is not a tech star,” he wrote in an email to police on Aug. 14. “The person currently working on it is not progressing fast enough and is not giving him enough insight. DPR previously fronted that he wanted to move slow (‘very slow to trust’) but the picture this message paints is he [is] thirsty for help. This quick shift of posture indicates he is really eager and will let us right in the front door.”

He continued: “The rate at which the walls are falling gives me a feeling that this will be successful. The way this is likely to unfold is he’ll have me working on this new system and I will be able to locate the system once inside. The system will not be at DPR’s house, it will be at a hosting facility somewhere. If the hosting facility can be made to cooperate there is a good chance of locating DPR as he connects to that system.”

Sadler did his early work with Roberts “in good faith.” By mid-September, they had negotiated a wage: $100 per hour to analyze potential risks, a figure low enough to be accepted and high enough to not provoke suspicion. Sadler said it was a justified trial period and that, if both parties liked the setup, they would renegotiate in three months. The trial also allowed Sadler to circumvent Roberts’ request to reveal his identity for security purposes.

An screengrab of a conversation between Roberts and Nod.

Through a Homeland Security intermediary, Sadler and Roberts exchanged hundreds of private messages on the Silk Road forum. In an attempt to become a routine in Roberts’ life, Sadler sent message after message, stopping just short of asking “How’s the weather?” He always asked questions in his messages, making it so that Roberts had reason to communicate back.

It worked. Sadler said that Roberts even spoke to him about administering servers for a new criminal enterprise unrelated to Silk Road, although he never went into much detail.

Note: Roberts mentions “this other project.”

Sadler was making real progress toward uncovering Silk Road’s servers, and he seemed to be gaining favor with the authorities he was collaborating with.

“We went from being adversaries to being very friendly,” Sadler continued. “Our guards went down.”

While he worked, Sadler believed that although “no one said it out loud,” his cooperation was meant to buy him leniency and maybe even a get-out-of-jail-free card.

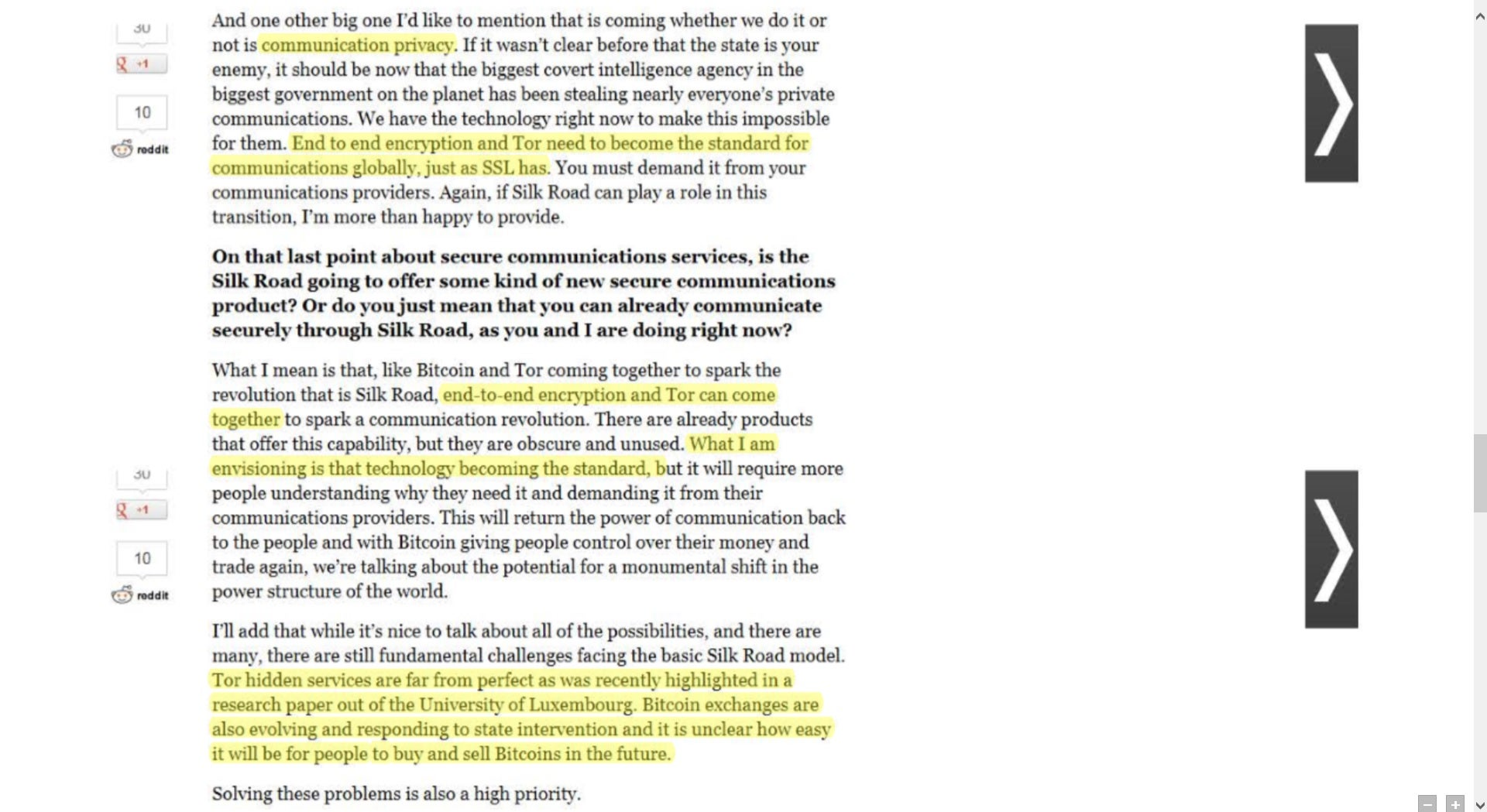

In emails between Sadler and law enforcement and forwarded to the Daily Dot, agents often sent pictures of other Silk Road suspects in the Seattle area, asking if Sadler recognized them. In August, when Dread Pirate Roberts’ Forbes interview was published, police sent a copy of the article to Sadler with highlights, notes, and questions about security issues.

The notated PDF file allegedly sent from Homeland Security officers to Sadler.

The Daily Dot reached out multiple times for comment from the federal prosecutor’s office as well as from Sadler’s defense lawyer. We have been declined each time.

Over the course of hundreds of emails and dozens of meetings, Sadler became candid with the cops as they worked toward a common goal. That was “a very good time,” he said. “I really enjoyed that.”

On Oct. 2, Ross William Ulbricht was arrested in the science-fiction section of a San Francisco public library, accused of being Silk Road’s Dread Pirate Roberts and of narcotics trafficking. It wasn’t Homeland Security, the department that Sadler had worked with, however, that made an arrest. It was the FBI in a separate investigation.

The FBI claimed that Ulbricht was speaking with an informant when he was caught. Sadler said it wasn’t him and doesn’t know who it was. In fact, when it comes to other police investigations into Silk Road, Sadler hasn’t said much at all.

With Ulbricht behind bars, Sadler suddenly became less useful to Homeland Security. The criminal complaint against him was unsealed. He was arrested and put on bond to await trial. The unspoken agreement Sadler anticipated was gone. He felt betrayed.

With Ulbricht behind bars, Sadler suddenly became less useful to Homeland Security. The criminal complaint against him was unsealed. He was arrested and put on bond to await trial. The unspoken agreement Sadler anticipated was gone. He felt betrayed.

“Oh,” Sadler said when asked how his life has changed since Oct. 2, “it’s gotten much worse.”

Sadler was kicked out of the condo where he had lived for seven years. He was called a danger to society by neighbors and has been unable to get a job, despite being “a very skilled computer programmer.”

In the aftermath of Silk Road’s demise, Sadler’s arrest made news around the world. Soon, his cooperation with police was revealed in a report by the Smoking Gun. Rumors have circulated that Sadler was involved in a National Geographic Channel show called Drug Inc., which featured Silk Road vendors in Seattle, while others accused him of giving away lists of customers and ratting out fellow vendors. Sadler denied those allegations—”It might have [been] Seneca, been another Seattle-based dealer I’ve met,” he said—though the police report indicates various documents were removed from Sadler’s apartment, including a list of shipment addresses.

Sadler’s bond agreement came with several conditions. He couldn’t leave the state of Washington, possess weapons or drugs, or contact anyone he worked with, including ex-girlfriend Jenna White. Sadler’s also subjected to random urine analysis and had to call into a computer system seven days a week to report to the police.

Not that any of that mattered to Sadler. He used methamphetamine and heroin in the lead-up to a court appearance and in express noncompliance with his bond conditions. He told me he skipped out on a urinalysis appointment he was instructed to attend. Soon afterward, he stopped calling the computer system. Despite repeated calls from his attorney and pretrial officer, he’d essentially gone off the grid.

“To your face they smile and act nice,” Sadler said, “but if they locate me, I’ll be burned at the stake.”

When Sadler went on the run, it wasn’t clear where he’d end up.

He claimed to have his car searched by professionals to see about a tracking device, and our phone calls were increasingly erratic. He said he was buying and using cocaine during several of them.

Sadler was made aware of the warrant for his arrest by his attorney, according to emails he forwarded to the Daily Dot. We could not independently confirm the warrant, despite multiple calls to the federal prosecutor and defense attorneys assigned to the case. On Nov. 13, Sadler said the U.S. Marshal’s Office visited his residence and discovered that he had moved on Oct. 31.

The way he sees it, Sadler was lied to by his pretrial officer and Homeland Security, which seemingly gave him little or no credit for his assistance leading up to Dread Pirate Roberts’ arrest. Despite emailed assurances from his attorney, Michael Filipovic, Sadler doesn’t feel like the Bureau of Prisons would take steps to protect him as a known informant.

“If you do a search for articles about this on the Internet and look in the comments, you will see the public perception is that I turned in all my customers and they are very angry,” Sadler said he told his attorney. “There is even a price on my head. There’s a phrase ‘snitches get stitches’—when I go to prison I am going to get harmed.

“So here I am, cooperating as best I can, and not only did I not get credit, people want me harmed and killed on the outside, and people will harm me or kill me on the inside.”

“So here I am, cooperating as best I can, and not only did I not get credit, people want me harmed and killed on the outside, and people will harm me or kill me on the inside.”

I last heard from Sadler on Nov. 6. in what was more than our 100th email. He told me enjoyed our “lectures” and laid out a plan for future lessons that included “Drug quality assessment, how drug dealers on the street work, drug weights, drug dealer lies, customer service, management and handling, mailing, marketing and branding, competitors to Silk Road, buying drugs online, handling yourself around drug dealers, and electronic security.”

The truth is that I enjoyed the lectures as well. They were the most interesting and informative phone calls I’ve ever made. I found myself looking forward to them and keeping my phone close by, just in case.

But then two weeks went by without word from Sadler. It had been longer still since he touched base with his family or friends, whom he pushed away during his rise as a Silk Road vendor.

“I’ve lost most of my social support,” he once told me. “When your mom calls, you can’t really tell her what you did that day.”

The future looked bleak. He had few options, nearly all of which included endlessly running with one eye always on the rear-view mirror.

“I’ve been in a pretty tough place,” he told me the last time we spoke. “It’s been a pretty tough time for me.”

Late on the night of Nov. 19, I received an email from Bobby Sadler, Steven’s father, telling me that Steven was in custody. He’s unhappy about being incarcerated, Bobby said, but he’s in good health. Bobby was unsure of just how his son ended up in jail.

When Steven called his father, he requested that I send him a copy of this article to read.

“Steve believes you will send me that article. If you do send me a copy of that article, I will e-mail it to Steve as he requested,” Bobby explained. “Since Steve’s incarcerated, the corrections officials read all his correspondence including incoming and outgoing e-mails. He believes there is nothing in the article I requested that will hurt his criminal defense case.”

Illustration by Jason Reed