Earlier this month, fans of Bitcoin—the world’s most popular digital currency—were caught in a whirl of panic as one group threatened to corner the market for new bitcoins.

GHash.io, a Ukraine-based collective of Bitcoin miners, recorded a massive spike in its computing power. Almost overnight, an organization that didn’t exist as recently as last summer, suddenly controlled 42 percent of all the world’s ability to create bitcoins.

Reading influential forms like Bitcointalk.org and Reddit’s r/bitcoin page that day, one would be forgiven for coming to the conclusion that the development signaled the imminent collapse of the Bitcoin economy. Some went as far as advocating for commencing a distributed denial of service attack (DDoS) on GHash, aimed at temporarily crashing the group’s servers, as a form of protest against the organization’s dominance.

The fear was over something called a “51 percent attack.” An entity that controls over half of the processing power on the entire Bitcoin network can use that power to engage in a whole mess of shenanigans, like getting away with spending a single Bitcoin an infinite number of times, or preventing other Bitcoin users’ transactions from going through. At 42 percent, GHash was short of the full amount it would need to cause serious trouble, and the group has since taken steps to drop its processing power down to an even less threatening level.

The collective backlash to the incident, however, is indicative of a creeping unease about powerful mining pools. The pools are a group of secretive organizations not only responsible for the creation of nearly every Bitcoin that comes into existence,but also for organizing the more than 60,000 Bitcoin transactions that occur every single day.

The largest Bitcoin mining pools are multimillion dollar businesses, and their operators have become some of the most powerful individuals within the world of cryptocurrency. Their seemingly inevitable rise may be one of the best examples of how a system held up by its techno-libertarian boosters as joyously anarchic and decentralized is becoming increasingly formalized, structured, and dare we say, corporate.

How Bitcoin mining works

Jeff Garzik may be the textbook definition of a Bitcoin early adopter. After reading a Slashdot article about the currency in mid-2010, he dove head-first into the world of virtual currency. He joined Bitcoin’s core development team, a small group of programmers who worked tirelessly to improve the technical integrity of the Bitcoin network. In the early days, he sent software patches directly to Satoshi Nakamoto, the enigmatic and pseudonymous creator of the currency who later vanished without a trace.

“I was one of the first people in the U.S. to get specialized hardware for Bitcoin mining,” Garzik boasted with a sly chuckle. ‟At first, I was able to use it to mine with some success, but eventually it would take me four weeks before I ever solved a block. And that was if I got lucky.”

“I was one of the first people in the U.S. to get specialized hardware for Bitcoin mining,” Garzik boasted with a sly chuckle. ‟At first, I was able to use it to mine with some success, but eventually it would take me four weeks before I ever solved a block. And that was if I got lucky.”

The difficulty Garzik faced in mining on his own, even in those early days using the most cutting-edge hardware available anywhere, is a perfect example of why solo mining was bound to become a fool’s errand.

Nakamoto’s 2008 essay outlining the the concept for Bitcoin wasn’t the first time someone had proposed creating a decentralized virtual currency, but it was the first time anyone had come up with a good solution to the problem of double spending. If a Bitcoin is, in reality, just a file sitting on a hard drive somewhere, what’s to prevent someone from making five copies of that file and then sending it to five different people, disingenuously telling each recipient their copy is the only one? Without a way to independently verify the legitimacy of each transaction, the element of scarcity necessary to attach a real-world value to a string of ones and zeroes flies out the window. Bad money chases out the good and the virtual currency becomes instantly worthless.

Nakamoto solved this problem by creating a public ledger, called the blockchain, into which every Bitcoin transaction in existence is recorded. Adding new pages, called “blocks,” to that ledger requires computational heavy lifting from computers connected to the Bitcoin network. In order to entice people to do this work, Nakomoto proposed a process of validating transactions, dubbed ‟mining,” where all computers on the network running a specific piece of software compete to solve a complex mathematical equation. The first person to publish the correct answer “discovers” the block and gets to collect the brand new bitcoins.

Because there’s a limited amount of space in each block, such that the entire worldwide Bitcoin network can only handle seven transactions each second, people can tag on an additional fee on their transactions to entice miners to put their transaction in the next available block and avoid possibly having to wait. These additional fees are added onto the bounty received by the person who discovers the block.

Mining is a zero-sum game. While every mining computer connected to the network is trying to solve the next block, only one of them will actually be rewarded for accomplishing the task. The result is a technological arms race, with miners aiming extremely specialized, extremely high-powered computer systems at the problem in an attempt to get there first.

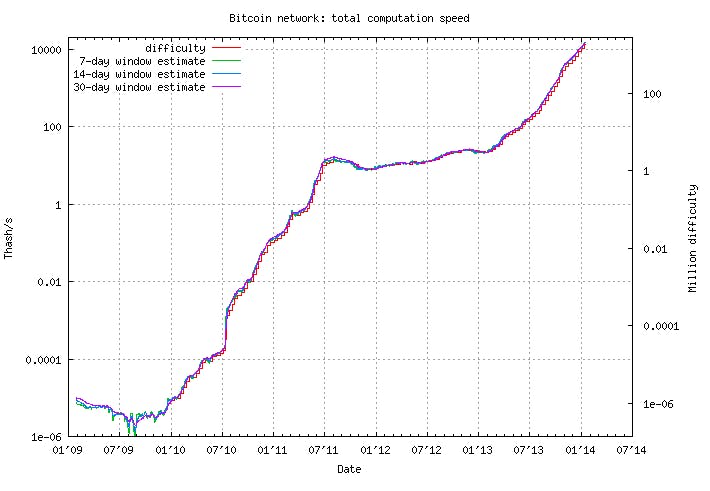

As more computing power is put to the task of discovering new blocks, the difficulty of the problems those computers are required to solve rises correspondingly:

Chart via bitcoin.sipa.be

As the price of a Bitcoin increases, mining becomes more attractive as a money-making activity, which leads to more people wanting to get into the mining game. But as more people join the network, mining becomes more difficult, necessitating people to spend more on mining hardware, which further increases difficulty of mining. This cycle goes on forever until the field becomes so competitive that it’s difficult to get a return on any investment in mining hardware.

The solution to this problem is collective action—hooking up with a large group of other miners to form a pool.

“Mining bitcoins is analogous to buying lottery tickets. Solving a block is like winning the lottery because a lot of it is essentially random,” Garzik explained. ‟Having more computer power is like buying more lottery tickets. Joining together in a pool is like a whole bunch of people throwing their lottery tickets into a big pile and divvying up the spoils if anyone the group comes up with the winning number.”

Since running the equipment required to effectively mine Bitcoin (and keeping it cool enough to prevent overheating) requires a large amount of power, pools allow miners to maintain a steady flow of income and make a rational cost-benefit analysis of whether mining is going to be a money-making or money-losing proposition.

The realization that pools were the ideal way to structure mining hit the Bitcoin community in a wave. The first pool, a French operation dubbed Slush’s Pool, opened for business in late 2010. The following year saw the creation of 18 more.

“Pools are an inevitable result of the way Bitcoin was set up,” Garzik said. ‟If you want a steady income stream, you have to organize mining this way.”

The necessity of Bitcoin mining pools

When Peter Leurs started Triplemining with a few friends in 2011, the primary goal wasn’t to make money.

Just as being rewarded with freshly minted bitcoins is merely an inducement to convince people to actively maintain the network, Leurs argues his Belgium-based mining pool is a labor of love aimed at protecting the network, rather than a pathway to earning virtual millions:

“We currently operate our pool as a hobby, and we do it out of ideology,” he told me. “We’re not making any profits on our pool, we can barely pay for the five servers we are currently operating to run the pool (and that’s excluding the backup servers). We are putting tons of energy in handling support mails and working on our servers just to keep our pool up and running. We’re all doing this unpaid and after our full-time day jobs. Other pools are ran by people doing this as a full-time job as they earn enough of profits by running the pool (or indirectly by selling related services). We are doing this as a hobby, to ensure that Bitcoin remains properly protected.”

“We currently operate our pool as a hobby, and we do it out of ideology,” he told me. “We’re not making any profits on our pool, we can barely pay for the five servers we are currently operating to run the pool (and that’s excluding the backup servers). We are putting tons of energy in handling support mails and working on our servers just to keep our pool up and running. We’re all doing this unpaid and after our full-time day jobs. Other pools are ran by people doing this as a full-time job as they earn enough of profits by running the pool (or indirectly by selling related services). We are doing this as a hobby, to ensure that Bitcoin remains properly protected.”

Triplemining only has about 1,000 users actively mining on a regular basis, but they’re able to discover a block every few days. At the current exchange rate, that single block could be cashed out for just over $22,000 U.S. Divided a thousand ways, that’s not a huge amount of money—not enough to retire on, certainly—but it covers the cost of running the machines and justifies having to wake up at 4am every so often when the system crashes.

While Leurs’s pool is essentially a passion project, there’s no mistaking the larger pools for anything other than big businesses hungry for growth with an eye toward the bottom line.

‟The pool size matters. The larger the pool, the more blocks will be found, and the more stable your payouts will be,” Leurs explained. ‟However, in the long run, the chance of finding a block is equal for everybody, and all pools should reward the same payout on average in the long run. There is a minimum critical mass, however, if your pool is too small, then people will abandon it if it doesn’t find any blocks in a reasonable time.

“Most people want daily payouts, so larger pools do attract more people. This is unfortunate, as more diversity in the pools is better for Bitcoin in the end.”

Since the mining software allows individual miners to switch between pools with a click of the mouse, it’s simple for people to move from one pool to another. GHash, the pool whose power was so enormous it posed an existential threat to the currency, is less than six months old. GHash grew so quickly thanks to its relationship with another company, Cex.io.

The success of Cex, which is run by the same people who manage GHash, is predicated on the assumption that there are a lot people out there who see Bitcoin mining simply as an investment vehicle. If all you want to do is spend money on a mining rig and then reap the rewards, a lot of the technical challenges that come with it suddenly seem like unnecessary headaches. Cex lets people effectively rent mining hardware they never have to see or actively deal with. If someone hires Cex to mine in their name, the only problem they’ll have is how to spend their money.

As both the value and public profile of Bitcoin has skyrocketed over the course of 2013, an ever-growing number of people suddenly saw Bitcoin mining as the closest they’d ever get to legally printing their own money. Cex turned out to be the simplest way to get there. Until the uproar earlier this month, when the massive backlash forced the company to change its exclusivity policy, all of Cex’s processing power was poured directly into GHash.

Leurs worries that services like Cex could destroy Bitcoin’s individualistic ethos. ‟For me the real problem is …[Cex]. People rent hashing power, so they basically give a lot of money to one company to obtain a large quantity of mining power,” he said. ‟Should GHash ever misuse their position, people can respond by changing their miner not to point to that pool, quickly punishing them for their abuse. However, with Cex, all the mining power is centralized in their data center. Should they ever decide to abuse their … power, there is much less we can do, as the [mining power] is under their direct physical control. I therefore strongly recommend for miners to not rent hash power, but run their mining rigs themselves.”

Leurs insists he isn’t accusing Cex or GHash of any wrongdoing because, at the end of the day, their business model depends on a very large number of people putting their trust in the security of the Bitcoin network. Any action that compromised that network would only damage Cex in the long run. However, in light of prior accusations that GHash engaged in double-spending shenanigans at a Bitcoin gambling site, there’s a sense that further centralization of mining operations creates a larger opportunity for someone to cause trouble.

While the 51 Percent Attack is a well-known problem in the community, there’s already evidence that miners will start streaming out of a pool as soon as it comes perilously close to hitting that magic number. However, some have speculated a far lower processing power threshold is necessary for a pool to start seriously undermining the system for its own personal gain.

Last year, a pair of Cornell computer scientists described something they called a ‟selfish-mine” attack. Using a complex strategy of selectively waiting to notify the network about the blocks they’ve solved, powerful pools can game the system to earn a significantly greater share of new bitcoins than their computer power would typically allow. This trick basically leads other pools to waste time attempting to find blocks that have already been located, while the “selfish miner” reaps all the rewards.

While author Emin Gun Sirer admits there’s no hard evidence anyone has actually attempted this tactic, a group’s ability to successfully carry it out grows as its size increases. ‟Above 33 percent, selfish miners do not need to race against the other pools; their sheer size means that they themselves will be able to follow up on their own blocks and earn excess profits,” he explained.

GHash and Cex didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

This tight-lipped attitude is common among mining pools, especially toward the larger end of the spectrum. The Daily Dot reached out to over a dozen groups but only received responses from two of them. ‟I think that there is really no incentive for these pool operators to talk to the media,” speculated Daniel Cawrey, a contributing editor at the indispensable cryptocurrency news site CoinDesk. ‟For many countries, mining is in a gray area policy-wise, and these pool operators are doing quite well financially staying out of the limelight.”

The future of Bitcoin mining

Despite having just scored a major victory for Bitcoin miners across the United States, Russ Smith wasn’t particularly enthused about his own future as a virtual currency creator.

Last year, Smith, who runs the consulting firm Atlantic City Bitcoin, sent a letter to the U.S. Treasury Department asking for clarification on whether individual Bitcoin miners had to register as money transmitters. In December, the Treasury responded by declaring miners were not money transmitters and therefore don’t have to jump through a litany of hoops like carrying high levels of insurance and subjecting themselves to regular audits. Many smaller miners feared the costs of meeting these requirements would put them out of business.

Last year, Smith, who runs the consulting firm Atlantic City Bitcoin, sent a letter to the U.S. Treasury Department asking for clarification on whether individual Bitcoin miners had to register as money transmitters. In December, the Treasury responded by declaring miners were not money transmitters and therefore don’t have to jump through a litany of hoops like carrying high levels of insurance and subjecting themselves to regular audits. Many smaller miners feared the costs of meeting these requirements would put them out of business.

Even so, in an interview a few weeks later, Smith admitted he had strongly considered getting out of the mining game altogether. Despite the regular income pools provide, he complained that breaking even on mining is an increasingly difficult proposition for anyone but the largest players. “More people who have struck out on their own in Bitcoin mining recently have lost money recently than made money,” he said with a sigh.

He added that securing the specialized equipment necessary to compete has become a hassle. “It’s very hard to get Bitcoin mining hardware these days, you pretty much have to build it yourself,” he said. ‟The companies have no incentive to deliver units that they can operate themselves. Many companies didn’t deliver at all and some have disappeared with the money…. Why should a vendor sell you a piece of equipment that they can just plug in themselves and start making money?”

In a sense, miners like Smith are victims of their own success. Through mining, they’ve maintained the health of a network that needs their hard work to survive. In return, they’ve been rewarded with an asset that’s quadrupled in value in the past six months alone. But that increase has brought an influx of new people who see mining less as an opportunity to make history than as a way to make money. These new entrants have professionalized the industry to a point where it’s barely recognizable to the handful of gearheads who plugged their home computers into the system back when Bitcoin was a secret club known only to a select few.

To hear Cawrey, the CoinDesk editor, tell it, the rise of the pools was an unavoidable result of that professionalization. ‟While it’s making the network more powerful … the level of concentration of these major players is a concern,” he insistsed. ‟Years ago we had a lot more banks in the United States than we do now and that consolidation has created a lot of problems. I’m not saying its a perfect analogy, but I’m afraid something like that could happen to Bitcoin.”

Illustration by Jason Reed