Stay cool, calm down, breathe easy for a while, the Internet tells me. But breathing gets harder when you’re wading in death threats, rape threats, or hateful epithets.

On any given morning, I start my day by checking Facebook messages, emails, and Twitter mentions—filtering out anything that sounds less than welcoming. A wise author, Dale Carnegie, once wrote that an individual’s name is the most pleasing sound to them in any language. But oftentimes, before I hear “Good morning, Derrick,” an unsuspecting troll writes that I deserve to die.

As a professional, I’m expected to simply shake it off or understand that it comes with the territory of living in public. After all, it’s just the Internet, right? It shouldn’t be taken so seriously. But it’s that very attitude—one that’s internalized from friends, employers, social media platforms, and even law enforcement—which sustains a culture that ignores the harrowing specter of online harassment.

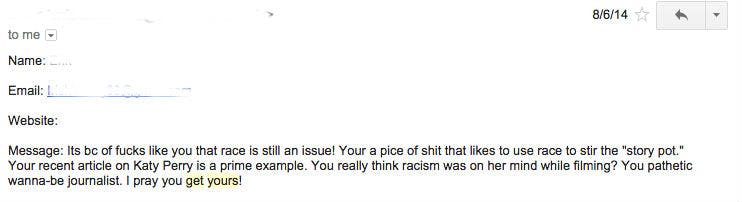

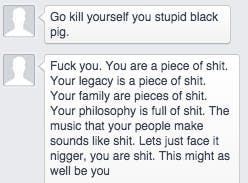

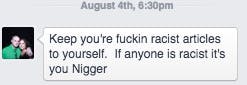

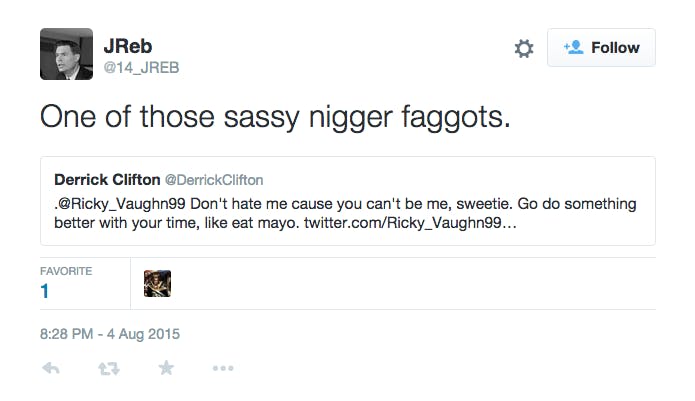

The very people who should claim responsibility for fixing the problem tend to act as though they don’t see it, but those who have been the victims of harassment can’t pretend messages like these don’t exist:

If anyone in real life ever told me that I need to be killed, followed by a racial epithet, the police might take it seriously. Should that sentiment have arrived in the form of snail mail, perhaps the people in charge would share concern. But most online users on the receiving end of harassment and death threats are left to their own devices, and wait at the mercy of social media platforms that may never read their abuse report or police officers who laugh them out of the station.

That sad reality informs how many online victims devise their own coping mechanisms, defense strategies, or proactive measures to combat online harassment—because too few community members and people with institutional power treat it as though it’s not a real-life issue.

Take, for instance, Mia Matsumiya, a vocalist who blogged for a span of roughly seven years about music while living in New York. During and after her blogging days, which ended in 2010, she received so many creepy, abusive, and dangerous messages from strangers that she began screenshotting and archiving anything that she felt elicited an emotional response.

If anyone in real life ever told me that I need to be killed, followed by a racial epithet, the authorities might take it seriously.

The notes, overwhelmingly male-driven, detailed rape fantasies, or indicated unwelcome, unprompted sexual advances. “What will you feel if I ever enter inside you. Are you virgin flesh? I don’t think so,” one undisclosed Facebook user wrote. But she kept the messages because she wanted to study them after the fact, and because she felt she needed to do something about it. After all, who else would?

As Matsumiya told BuzzFeed’s Rossalyn Warren, she thinks the messages are “degrading, dehumanizing, and disgusting” and doesn’t view them as compliments in any way. “I sincerely want the attention to be focused on the messages, and not myself,” she said. “I want these messages to demonstrate the crazy, awful, and unacceptable things women receive online.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/862EV8k8Xd/

Matsumiya’s approach is one way of confronting online harassment head-on, and has been utilized by many other women with similar experiences. During last year’s Gamergate controversy, for instance, games reviewer Alanah Pearce found herself on the receiving end of online abuse and rape threats. However, she devised a novel way of holding the men (and boys) accountable: by finding and emailing their moms about it.

In reality, online harassment doesn’t only hurt mentally or emotionally. It could also lead to physical harm.

“It was just a way to try to reach a resolution, to productively teach young boys it’s not OK to be sexist to women, even if they’re on the Internet,” Pearce told the Guardian, “that they are real people and that there should be actual consequences for that.” In at least one case, the mother wrote back assuring Pearce that she’d talk to her son about the harm he caused, apologizing on his behalf.

Far too often, in the wild wild west of the World Wide Web, the victims and survivors of online harassment have no choice but to take justice into their own hands, because they have no other recourse. Instead, those who endure the abuse live with the expectation that they’ll handle it on their own, engage in self-care, and operate by the “sticks and stones” mantra.

But in reality, online harassment doesn’t only hurt mentally or emotionally, it could also lead to physical harm should it escalate—something Matsumiya reportedly feared before her Internet stalker was arrested in public, for a different case.

Sometimes young boys on Facebook send me rape threats, so I've started telling their mothers. pic.twitter.com/0Cbs81eXiE

— Alanah Pearce (@Charalanahzard) November 28, 2014

Yet online communities, employers, tech giants, and law enforcement agencies continue struggling to move beyond an individualistic frame of eradicating online harassment. Instead, social media interactions get reduced as mere annoyances that preclude human ability to engage in face-to-face, interpersonal contact.

There’s something to be said about approaching new technologies in a way that’s more authentically human and discerning. It’s indeed possible to engage the Internet in ways that welcome new ways of staying connected, without allowing the mediums to erase our real-life sensibilities; without forgetting that we should treat others as we’d want to be treated. But when laptops and smartphones power down, online mistreatment simply doesn’t just go away. Those on the receiving end must still find a way to manage somehow.

Beyond widespread apathy or confusion about how to handle online harassment, there’s often little-to-no support for people routinely targeted by abusers.

Julianne Ross, an online editor, knows this all too well. As Ross writes at Wired, a critical 2014 article she penned about “men’s rights” activism elicited multiple pages of emails with violent threats, which she took seriously—but her experience reporting them to law enforcement didn’t measure up.

“Unfortunately, the police had no idea what to do. They quickly sent me on my way (to be fair, one officer did say he’d like to punch the emailer in the face), and my search for offline justice was over almost as soon as it began,” she noted. “Digital harassment typically doesn’t lead to rigorous investigations, legal prosecution, nor even basic sympathy, in large part because of this persistent notion that what happens on the Internet doesn’t count—a notion bolstered, no doubt, by assertions that technology is destroying human interaction.”

Beyond apathy or confusion about how to handle online harassment, there’s often little-to-no support for people routinely targeted by abusers. In the process, trolls and online thugs get away with silencing any voice perceived as adversarial. And they persist because they are fully aware that there’s no real way of holding them accountable—a problem with roots in the pervasive sentiment that online interactions aren’t the real deal.

But until law enforcement and tech companies create systems and standards for holding online abusers accountable, a cultural shift matters all the same. The actual or perceived sense of safety and security of people in online communities should take precedent over any impulse to minimize online harassment.

Those who deal with it online harassment on a routine basis should not be shamed, nor should they be scrutinized, for how they cope or fight back. The Internet should affirm and support them instead.

There are a few ways the Internet can work cooperatively to curb the abuse. From time to time, many members of my online networks—myself included—have begun sharing screenshots of questionable emails, tweets, Facebook messages, and other communications that include death or rape threats, epithets against marginalized groups, or that indicate a stranger flagrantly disregards requests to stop. By sharing the experience with others as deemed necessary, as Matsumiya and other women have done, it helps demand accountability for the abusers and for the social media platforms that harbor them. Even further, it invites others to help protect and care for those who need the uplift after enduring harassment.

When called into circles of care and protection, community members should first practice empathy: by expressing their concern for the aggrieved and asking how they can be of help. While coping with threats to one’s safety and well-being, knowing others who recognize the struggle and offer their assistance can make all the difference. It’s the security of knowing that you’re not alone.

Those who deal with online harassment on a routine basis should not be shamed, nor should they be scrutinized for how they cope or fight back. The Internet should affirm and support them instead.

Derrick Clifton is the deputy opinion editor for the Daily Dot and a New York-based journalist and speaker, primarily covering issues of identity, culture, and social justice.

Photo via Carolyn Tiry/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0) | Remix by Dell Cameron