Who am I IRL (in real life)? Male, white, bespectacled, Oxford shirt, mid-20s, organ donor.

But in another, truer sense, this is also me:

— Cooper Fleishman (@_Cooper) February 11, 2014

And this:

What is “me irl”? It’s tough to define, but I’m sure you’re getting the hang of it. It’s not an ugly, #nofilter selfie at 7am, when I’ve got a morning deadline and a hangover-induced bloodlust for Gatorade and bacon. It’s more of a dramatic representation of the lunacy of my life—our life, our shared experience—on the Web.

Me on the Internet, 1999–2014 RT @gxrdiner: he just keeps getting angrier pic.twitter.com/CxtYDw6Wr2

— Cooper Fleishman (@_Cooper) January 26, 2014

The meme, if you can call it a meme, is profoundly silly, relentlessly self-deprecating, and delightfully open-ended. It’s Homer Simpson ringing a doomsday bell with a sign that reads “The End Is Near.” It’s a miniature horse with a pizza on its back. It’s a little kid wearing a shirt that says “Booty Is Life.” It’s a guinea pig in a tiny wagon, a depressing “Area Man” headline, a bottle of Hendrick’s, Pooh Bear staring at his pudgy belly, a skeleton, or a stock-photo model with a ’90s-era keyboard and a sweater that says “Geek.” Confusingly, “me irl” can also just be you, in real life, without a shred of irony. Anything goes.

me irl pic.twitter.com/gAWZs0HTp5

— Lana Berry (@Lana) March 5, 2014

me irl pic.twitter.com/bFt8q7twA7

— Jessica Misener (@jessmisener) April 29, 2014

Me IRL: pic.twitter.com/CPBVGFFHhT

— David Weiner (@daweiner) March 7, 2014

Me IRL https://t.co/ohwycL8NGB

— Anthony De Rosa (@AntDeRosa) February 23, 2014

me irl making some #content pic.twitter.com/GMeqd31QXj

— alfred (@digimatized) February 25, 2014

If you trace “me irl” back far enough—through the annals of Google history, past the modern eras of Twitter and Reddit and even the anarchic mid-2000s funhouses of 4chan and Something Awful—you’ll find the meme’s moment of origination. It took some digging, but I found it—what I believe is the very first true “me irl” published on the Internet. And it’s a doozy.

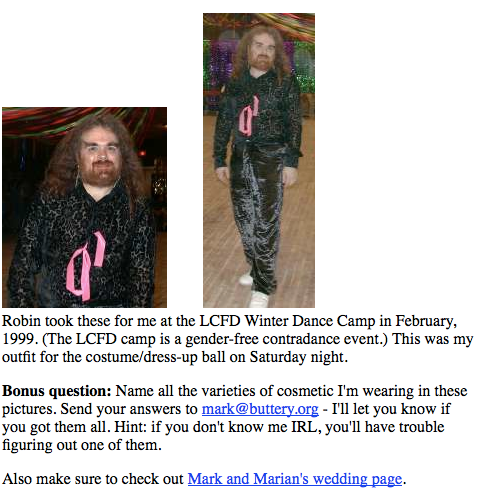

Mark’s Picture Gallery, 1999.

Back when the Internet was new, the phrase “IRL” was simple shorthand. Saying “me IRL” didn’t stand on its own as a statement of self; instead, it was used to say, “This conversation is over—talk to me in real life.”

The Web, of course, was a wholly different place 20 years ago, before our online experience became an integrated aspect of our real lives. Nobody really lived on the social Web, as we do now. It was more like a large encyclopedia we opened to find facts, or JPEGs of Jenna Jameson.

Wary of exposure, proto-netizens of the 1990s used pseudonyms to protect their non-Web identities. And when they spoke to people they met on the Web, they said things like “Talk to me IRL” and “Well, if you knew me IRL …” Opening up your life to strangers was a brand-new experience, and the phrase “in real life” was often used defensively and stubbornly to distinguish the meatspace from comment threads. It basically meant “you don’t know me, so shove off.”

But in that period, our Internet experience was becoming more closely tied to real life. Not only were people more comfortable sharing their personal information, but the idea of “real self” and “Internet self” began to merge as well, and spaces began to form on the Web where users could live as something in between human and avatar.

Those spaces appeared first in online furry erotica communities.

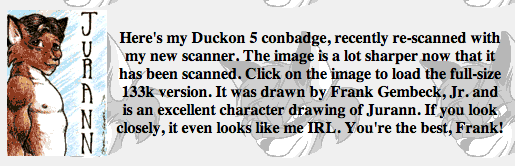

Jurann

In 1997, Jurann Foxtail was an aspiring and artist. He was also a big-name participant in online furry fandom, a subculture centered on anthropomorphized animals with (sometimes sexual) human characteristics and personality traits.

Home page, jurann.furcen.org, 1996.

“Ever since I was old enough to know the difference between man and animals, I always liked animals more and wanted to be one myself,” he wrote on his website sometime between 1997 and 1999. “The VR role-play and interaction as a furry anthro is the best current extension of exploring this dream.” He added that he is now in the “highest level” of anthropomorphics.

Jurann frequented an IRC channel called Yiffnet, in which he chatted with other furs and role-played various personas. He ran an online role-playing game called FuroticaMUCK (“multi-user created kingdom”), where he spent most of his time online. But he was starting to explore webpages, which he called “great primary resources … for finding new furs to either meet IRL or look out for online.”

Jurann’s website, jurann.furcen.org, has an About page (published in 1997, last updated in January ’99) in which he posted his conbadges, portraits of himself submitted by other members of the fandom. They’re not humans—they’re erotic, muscular, genderless foxes with ambiguous genitalia. “It’s a great study of my character,” he says of one badge. On another: “The flaming red aura doesn’t do much for me.”

But at the very top of the page, he posted one of his favorite images. It’s more cartoonish than some of the rest, but it seems to capture his “character” best of all.

“If you look closely,” Jurann wrote, “it even looks like me IRL.”

About page, jurann.furcen.org, 1997–1999.

What makes this last line stand out? This is the first instance I can gather of someone using the phrase “me IRL” to refer to an Internet persona. If so, it marks a substantial shift in our acceptance of the Internet as part of our lives. One could reasonably extrapolate that this—a crude drawing of an erotic human-fox hybrid—represents a turning point in the social Web, a moment (or the moment) in which our real lives and our Internet lives began to blur.

Depending on how you read the line, Jurann could have been hinting that the erotic fox looks like either his human form or his Jurann form. Either way, the line blurs all the same—he recognized he has no fixed appearance or identity in this new online space.

Jurann didn’t return my requests for a Q&A to clarify. But on his site, he went into detail about where he, as a member of the furry fandom, personally sat in the late-’90s continuum between online and IRL. Jurann explained that he has chosen not to distinguish between his Internet self and his true self (emphasis added):

While it is sometimes difficult for some (including myself) to either separate [virtual reality] from [real life] in their furry lives, or integrate it completely, I have chosen the latter and found it works quite well with my needs and living. Jurann is basically me in every way mentally, but physiology different online. When you talk to Jurann, you are talking to me, and when Jurann speaks, it’s me talking. In other words, there is no player or character, Jurann is the physical mask through which I exist online.”

Jurann went on to have a complicated relationship with his fandom. As the owner of the furry-focused marketplace Furbuy, he was permanently banned from a competing market, Fur Affinity, for “false threats” against users, “disruption of the community,” and “drama starting.” (This is according to Jurann’s entry on Wikifur.) In 2000, Jurann changed his species from a fox to a spotted hyena (below); in 2006 he switched to a raccoon, then later to a polar bear. He is now listed on Fur Affinity as an “ice bear.”

Jurann’s hyena fursuit, made in 2005. Photo via Wikifur.

Aja Romano is a fandom reporter since the early 2000s who now writes for the Daily Dot. She stresses that what “IRL” means to us is very different from what the phrase means to geek culture. “As a furry or a cosplayer or a fan,” she says, “the only time you could really interact in real life with other members of your community was at conventions.”

She continues:

“It’s not like today where you can just dress up and go to a Marvel movie premiere or have a fandom meetup in your town. It’s still not like that for furries. Conventions don’t function as normal public spaces—they function as extensions of geek culture on the Internet. And even many of *those* subculture-specific spaces are relatively closed off to the general public. So when a furry someone in a similar semi-public subculture uses ‘me IRL,’ they may still be using it like ‘me as I’d be if we could meet in a real-life space,’ not ‘me as I’d be on a street outside of geek culture.’”

In other words, furries and denizens of relatively unconventional Internet subcultures did blur that line between IRL and Internet, and they did so out of necessity. Their true selves don’t look like their real selves, their walk-to-the-curb-to-grab-the-morning-news selves. Their true selves, the bodies and personas they find most comfortable to inhabit, may only be able to exist on the Internet.

r/me_irl

“I don’t actually like using the term ‘in real life’ to mean offline, as what happens on the Internet is still real life.”

That’s Devtesla, the founder of the subreddit r/me_irl, the Reddit forum that rocketed the meme to popularity in 2012. A Google Trends search makes this spike very clear:

The subreddit’s description:

The only good sub. Post things that aren’t actually you, but represent an aspect of yourself. All posts must be titled “me irl”.

On r/me_irl, there are strict rules for posting. Every submission must be titled “me irl,” no exceptions. And moderators are judicious about what they allow on.

“The sub is popular because we weed out the bullshit, and what’s left is pretty damn good,” one mod told me in a Reddit private message. He didn’t need to convince me. I find r/me_irl to be consistently, refreshingly funny, and there’s a surprising amount of creativity in the submitted GIFs and photos.

Unlike many memes on Reddit, “me irl” is not an image macro with the same joke structure laid out in Impact font. There’s limitless potential for expression. When I asked the moderator why he thought r/me_irl was so great, he answered, “Have you seen the other subs?” Fair point.

Then I asked him who he was IRL, and he responded (of course) with an image:

Devtesla, r/me_irl’s founder, has a mysterious, pseudonymous Internet persona. He runs a community called the Devtesla network, which he describes as “a robot that fights evil.” The network is hosted on Reddit, which he hates—he calls it “a terrible website for literal children and contains no worthwhile content (except for r/me_irl).”

In the Devtesla network’s About page, Devtesla himself provides a full manifesto about his mission and philosophy. Here, he writes about the complicated meaning of “in real life”:

I prefer the term “away from keyboard”, but I’m not about to change the sub to me_afk or anything. The meaning of the term “in real life” is basically already set, and I’m kind of undermining it anyway by having people post pics that aren’t actually them away from keyboard.

Would “me afk” be more accurate than “me irl”? I asked the moderator. “That’s stupid,” he said.

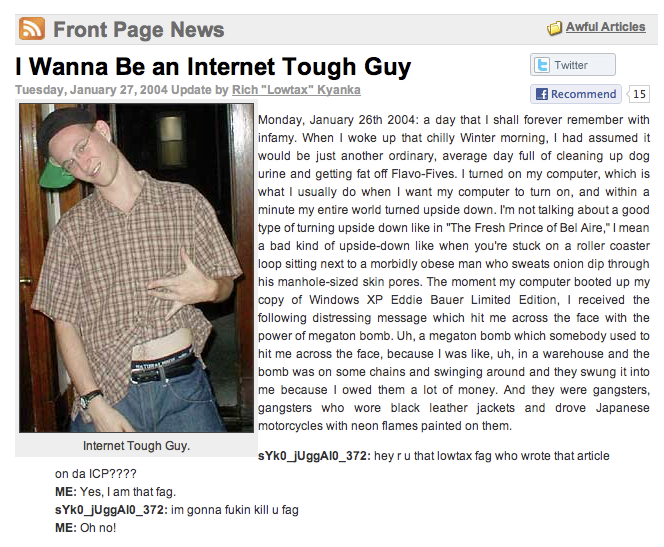

fight me irl

Before Reddit, the phrase “me irl” took off on Something Awful, whose subforum FYAD (short for Fuck You and Die) became an incubator for original content and irony-laden humor that, as John Herrman suggests, shaped the stream-of-conscious tone of Twitter coversations. It is now, as of Thursday, gone.

Via the Awl:

FYAD posts were short, image-heavy, and leaned heavily on context. The forum front page was a pink, broken cascade that was intentionally hard to follow, populated by users with tens of thousands of posts in their histories.

Eventually, “everyone funny moved on to Twitter,” says a former FYAD poster.

Something Awful thrived in the early to mid-2000s. Internet personas were commonplace, and users stripped the phrase “me irl” of all earnestness.

For an example, try a December 2006 thread titled “draw your dick,” which now thankfully hosts a lot of broken images.

“‘Me irl’ was just something that happened organically,” one longtime user told me. “Quoting any picture and saying ‘that’s me IRL’ was a joke in FYAD for so long I can’t even remember if it started there. It was never even really a meme, just seemed like an obvious joke.

“God bless that subreddit [r/me_irl] though,” he added. “It’s better than the rest of them by half.”

In the early 2000s, as image macros began to proliferate on 4chan and bodybuilding forums, that “you don’t know me IRL” sentiment of the pre-social Web was replaced by the phrase “fight me IRL.”

This meme stemmed from a 2002 thread about proper training methods on the forum Elite Fitness. One user came out swinging with the line “I’d like to see you say that to a powerlifter in real life, internet tough guy”—which, of course, sparked a meme of its own.

me irl

Who are we, really, when we tweet, Tumbl, or publish anything on the Web?

I can’t believe there was ever a time in which I blogged relatively true things about myself—my feelings, my gripes, my crushes, my hopes and dreams—openly, honestly, introspectively. But I did, as a tween in the early 2000s, on LiveJournal and Xanga and then even in Myspace notes (remember those?).

Twitter, the network I now use most often, is not that kind of place. Twitter is grouchy and sarcastic, and its messages are couched in more layers of irony than a cronut. Earnest tweets take honest-to-god courage: When I write something I feel is personal and honest and blast it out to 2,000 people, I get this tight feeling in my chest. It’s a very familiar sensation. I feel exposed and vulnerable, like my entire middle school just found out who I’m in love with.

If I want my followers to know the real me, my true feelings, I’m more likely to tweet “me irl” and attach a dog eating ice cream with human hands. Besides, a photo or a GIF fits much more easily into 140 characters.

Me IRL. pic.twitter.com/22p4nIXz5z

— Joshua Davison (@stringbot) April 28, 2014

I’m far from the only one who relies heavily on the phrase. Last year, I noticed that a prolific Twitter user, BuzzFeed’s Matt Bellassai, had turned it into kind of an art. He used “me irl” so often that his coworkers composed a listicle titled “Who Is Matt Bellassai, Really?”

I’ve met Matt Bellassai IRL, but I feel I know him best from this BuzzFeed post. You can learn about his childhood, about his career, about his fears, even his reaction to coffee (sorry, Matt). Even if it’s all a joke, it’s very intimate, in a way.

“Me irl” is now an accepted and acknowledged method of self-expression. It’s part of the fabric of Twitter, of Reddit, of Tumblr, of the whole atomized social Web, where most of us, on some level, are writing in character to appeal to a small community. Whether that character is a zebra, a rap-loving PT Cruiser, a media curmudgeon, or just a hyper-articulate, heart-on-sleeve version of oneself, it’s still a character—an altered, idealized, or exaggerated version of who we are when we close our laptops and walk away.

But here’s the problem with trying to separate “real life” and “online life”: We meet people on the Internet and work with them, collaborate with them, even fall in love with them. Our online habits can get us fired or arrested. The things we write, build, and code on the Internet can be major accomplishments on- and offline. (And for the past 10 years, we’ve been logging our everyday activity on an online social network without much concern.)

What we do on the Web is very much real. So is who we are, whoever that may be.

Photo by Kevin Dooley/Flickr (CC BY 2.0) | Remix by Fernando Alfonso III