Analysis

It’s opening night of SXSW, and the hottest happy hour in town is promoting sustainable soil inside an area Patagonia. The badge line isn’t budging—I assume the dreaded one-in, one-out policy is in full effect—so I move on.

At the South by Southwest Conference in Austin, Texas, known for hosting an abundance of technology managers with LinkedIn blogs, an industry reckons with its carbon footprint the best way it knows how: Feeding mushroom meat to thought leaders at a brand activation.

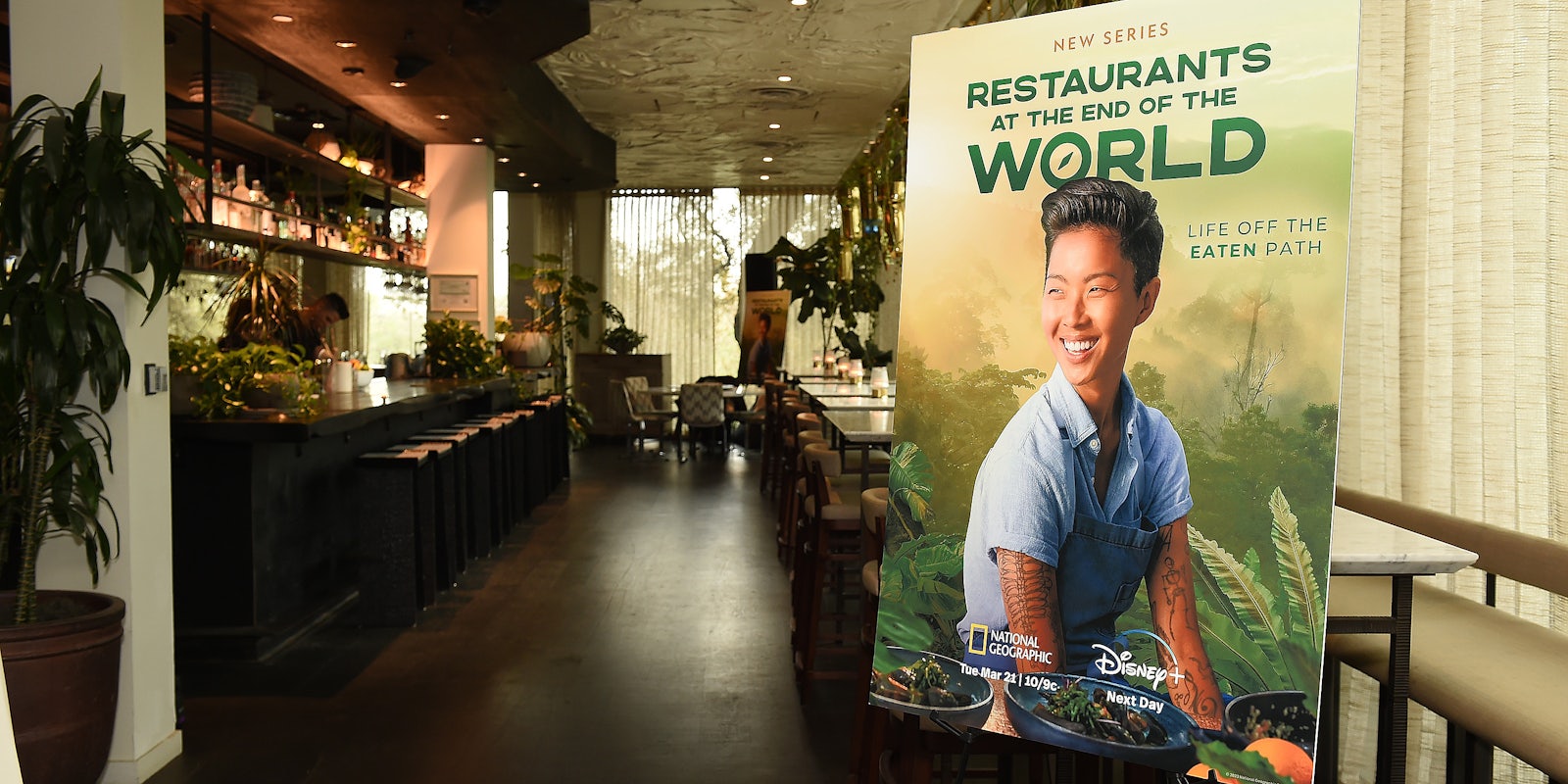

But here it’s not just the shadow of last week’s sudden Silicon Valley Bank collapse making the sector uneasy—it left at least one SX speaker scrambling for a payroll-saving wire transfer on her phone mid-presentation—it’s the looming dread of climate change. To borrow the title of a Disney+ series debuting this month from National Geographic and promoted during SXSW, the conference could aptly be described as Restaurants At the End of the World.

Shell Oil has taken over blues club Antone’s to host panels about Web 3’s role in a carbon-zero future. Climate change activists are protesting the energy sector and hosting Ben and Jerry’s-led ice cream socials. Volkswagen is previewing its new electric cars. Business leaders are taught about how to address their teams in crises during the “What to Say When the World Is Ending” panel. Kroger is throwing its weight behind the future of food. Clean energy infrastructure in the ocean is a trendy topic. So are enzymes that can compost plastic. So is net-zero housing. So are smart cities. So is hydrogen energy. So is looking to African countries “for a clean energy future.”

In other words, there are very earnest and arguably cynical solutions to climate change, an omnipresent problem affecting all life on the planet wherein every week it’s something new for humans to process. Like that the maple syrup industry may collapse.

Big tech wants to help. But everyone needs to address it; and so in Austin, there are oil corporations not using their logo on the marquee of their event.

‘Trust the energy guys’

Antone’s is really more of a brand than a beloved haunt. Named for the deceased organizer, alleged drug trafficker, and beloved University of Texas professor who taught a blues guitar class, Clifford Antone, the previous version of the eponymous nightclub was a charmless hole on West 5th that today does fancy ping-pong.

But the new Antone’s is an elegant and stunning mausoleum for blues. And Shell’s moved-in to talk about new technology for Monday’s talk, “How Digital and Web3 Tech Will Underpin a Net-Zero Future.”

Let’s translate.

Net-zero is the idea that yes, we’ll put greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere as a species, but we’ll balance that out with carbon-neutralizing and carbon-removing initiatives. Web 3 is a leftover buzz phrase from SXSW 2022, and it’s more of a philosophy: A decentralized internet that comes after the social media era, not beholden to Google and Facebook.

In niche Web3 communities that already exist and run on blockchains, artificial intelligence tools developed with open-sourced coding by armchair fans could be integrated into high-level workflows by Shell and Microsoft. Each offered speakers to the Shell House.

So basically you, the citizen coder, can help Shell become more efficient at solving technical problems. Panelists pointed to using infrared technology to ID methane leaks as concrete ways that technology innovation helps oil and gas fix problems.

OK, but.

“Shell’s operating plans and budgets do not reflect” its net-zero spending, argued climate activist and Scope3 CEO Brian O’Kelley at another SXSW panel. “These are companies designed to build massive industrial projects,” and so a clean energy transition that they talk about “is not a fit for them.”

O’Kelley says that we’re way past corporate pledges to reduce emissions, too.

“Targets don’t matter,” O’Kelley says. “I’ve had a weight loss target for 5 years. … How do we get past all this bullshit?”

I asked Shell CIO and SXSW speaker Jay Crotts. He thinks solutions to the energy “trilemma” will come from the oil and gas industry. (The three issues being access, affordability, sustainability of energy.) His take is that a giant company like Shell’s resources and elite human capital can make progress.

“I think those capabilities now are building wind farms. … Those capabilities are now building carbon capture servers in the subsurface,” Crotts says, saying that Shell has a “multi-billion dollar investment into the non-hydrocarbon environment.”

It does invest billions in low-carbon solutions. But as Bloomberg notes, simultaneously “selling oil and gas at record profits is a hard habit to break.”

“A lot of people said we have a supply problem. Get rid of the supply guys,” Crotts says. “Shell on a good day gets up to 2% of the energy hydrocarbons in the world.”

Shell in 2020 disclosed emissions of 1.3 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent, about 1.6%, according to Client Earth. Zooming out, as the EPA reports, “the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions from human activities in the United States is from burning fossil fuels for electricity, heat, and transportation.”

“If you cut off the Western oils,” Crotts says, “Does the world have no climate problem?” Or, he argues, “Does the Venezuelan oil that might be a little bit more pollution-rich fill the gap?”

Crotts continues: “We’re doing some of the most amazing things on the planet. We are trying to solve the problem. But the problem is the trilemma. … I predict the solutions will be these massive companies.” That’s because Crotts says they can scale-up these projects—a common argument made by the oil industry, apparently: The guys who know energy might as well lead the transition.

It was made at the Shell house, too.

It’s also an argument made in oil and gas advertising, another industry getting introspective at SXSW.

As O’Kelley, the CEO and climate activist, argues: “They’re saying the transition’s too hard. Trust us to handle it.”

“Your values are probably not that aligned with Exxon’s if you’re a young creative person in Austin Texas,” Duncan Meisel, executive director of Clean Creative, tells a panel about the carbon-rich supply chain’s relationship to the pop-up ads you see online.

The ad-man is here encouraging his profession to not work with fossil fuel companies. Thus far he’s gotten 500 agencies to stop.

“Don’t we want to have an ethical, moral high ground to stand on?” O’Kelley asks.

The 2023 SXSW features a desire for common ground and grapples with one large question, as he puts it: How to cause and participate in systemic change?

Eat the plastic

The tech sector’s SXSW menu for solving climate change has more choices than Cheesecake Factory. The most effective ideas, however, eat the elephant one bite at a time.

Four-hundred million tons of plastic will be produced in 2023, according to University of Texas professor Hal Alper. That number increases every year, he says. Maybe an enzyme discovered in 2016 and remixed by his research team can dissolve some of it?

A time-lapse video of his team’s research shows the enzymes eating all sorts of plastic goods from the grocery store into oblivion.

“Plastics are very easy to manufacture,” Alper says. “They’re cheap because they have very little impact in their manufacturing. But they’re expensive in terms of their long-term use.”

Named Fast-PETase and engineered via machine-learning algorithm, his team’s enzyme breaks down plastic at the molecular level “within 24 hours,” Alper shows SXSW on-screen. “It just begins to chew it away.”

It doesn’t work for all types of plastic, Alper says, but the enzymes came to humanity from nature, as a reaction to more than 100 years of plastic.

Similarly focused on scalable impact, Jason Busch, executive director of Pacific Ocean Energy Trust, is trying to build off-shore wind turbines in the ocean to produce clean energy. It’s a 10-year process to put one in the water, he says, considering permitting and surveying challenges and that “the U.S. has never had a coherent energy policy.”

His attitude seems to be both urgent and resigned to take it step-by-step. He’s a celebrated climate activist who, unlike O’Kelley, believes energy sector giants can help on clean energy. His co-panelist Olusola Dosunmu is director of global projects for DEMS LLC, a consulting firm that’s served the oil and gas industry. He says it’s a matter of repurposing the rigs in places like the Gulf of Mexico.

“You can reduce your environmental impact” by “using what’s there,” Dosunmu says. “We’re not going to start from scratch. It’s going to be a very smooth transition.”

That seems unlikely. Crystal Pruitt, external affairs lead for Atlantic Shores Offshore Wind, is tasked with establishing local relationships with those affected by offshore wind turbine construction.

“We’re going out into the communities that we’re impacting,” she says, and “explaining to them why we’re going to be tearing up their road.” She says it’s mostly communities of color who are impacted. This touches on yet another climate change hurdle: Environmentalism is a passion project for the sort of professional problem-solvers at SXSW; i.e. dudes in tech with lots of money.

“If a mother living in Newark has such poor air quality that her children developed asthma, … she doesn’t give a fuck about polar bears,” Pruitt says.

In National Geographic’s Restaurants At the End Of the World, Chef Kristen Kish highlights how remote cultures leverage land and sea to eat. Dinner is whatever they can catch that day. Hopefully SXSW’s industrialist climate goals prove useful to those locals.