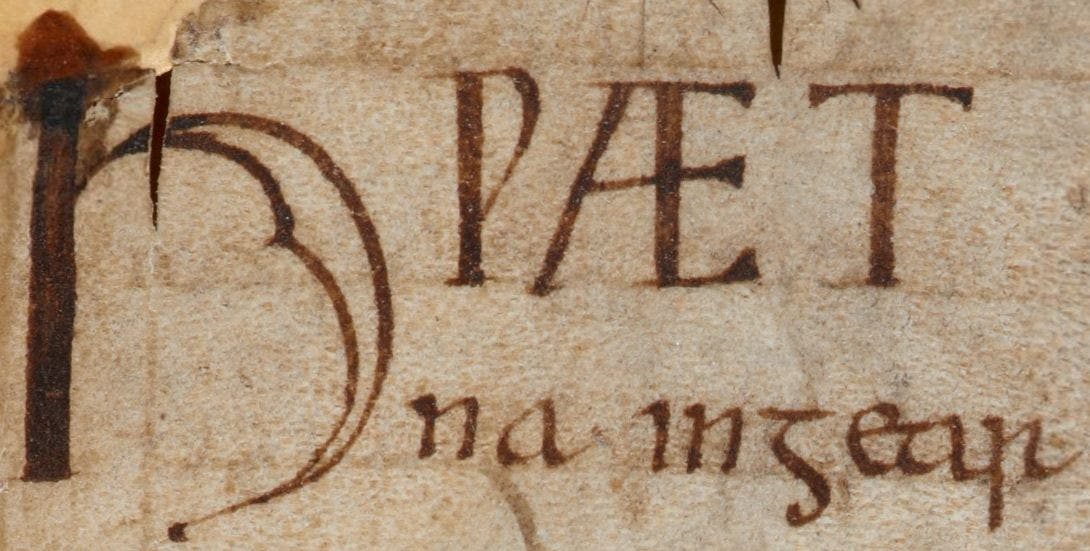

Listen! We have heard of the Spear-Danes,

How in days past the clan kings

Knew glory, those noble princes

Committed courageous deeds in battle.

The British Library is the orgasmatron for book lovers. I once spent time in the Library’s Ritblat Gallery and saw a draft of Wilfred Owen’s “Anthem for Doomed Youth” with Siegfried Sassoon’s handwritten notes on it. I almost fainted.

The Library’s devotion to digitizing its vast manuscript collection is simply daunting. Its plans include 25,000 documents.

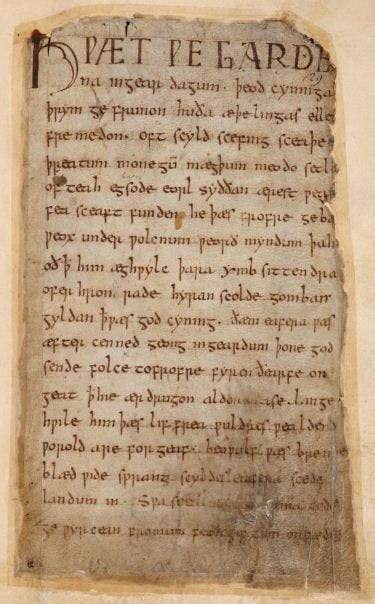

Its latest releases, courtesy of the Digitised Manuscripts division, include Leonardo Da Vinci’s notebooks (1478-1518), the Harley Golden Gospels, the Silos Apocalypse, the Golf Book, the Petit Livre d’Amour, and… Beowulf. (Yes, Beowulf, the Beowulf, with Grendel and Grendel’s mom and the dragon and Wiglaf and the whole kit and kaboodle—the manuscript, the poem, not the horrendous action-capture animated movie.)

The beginning of “Beowulf”

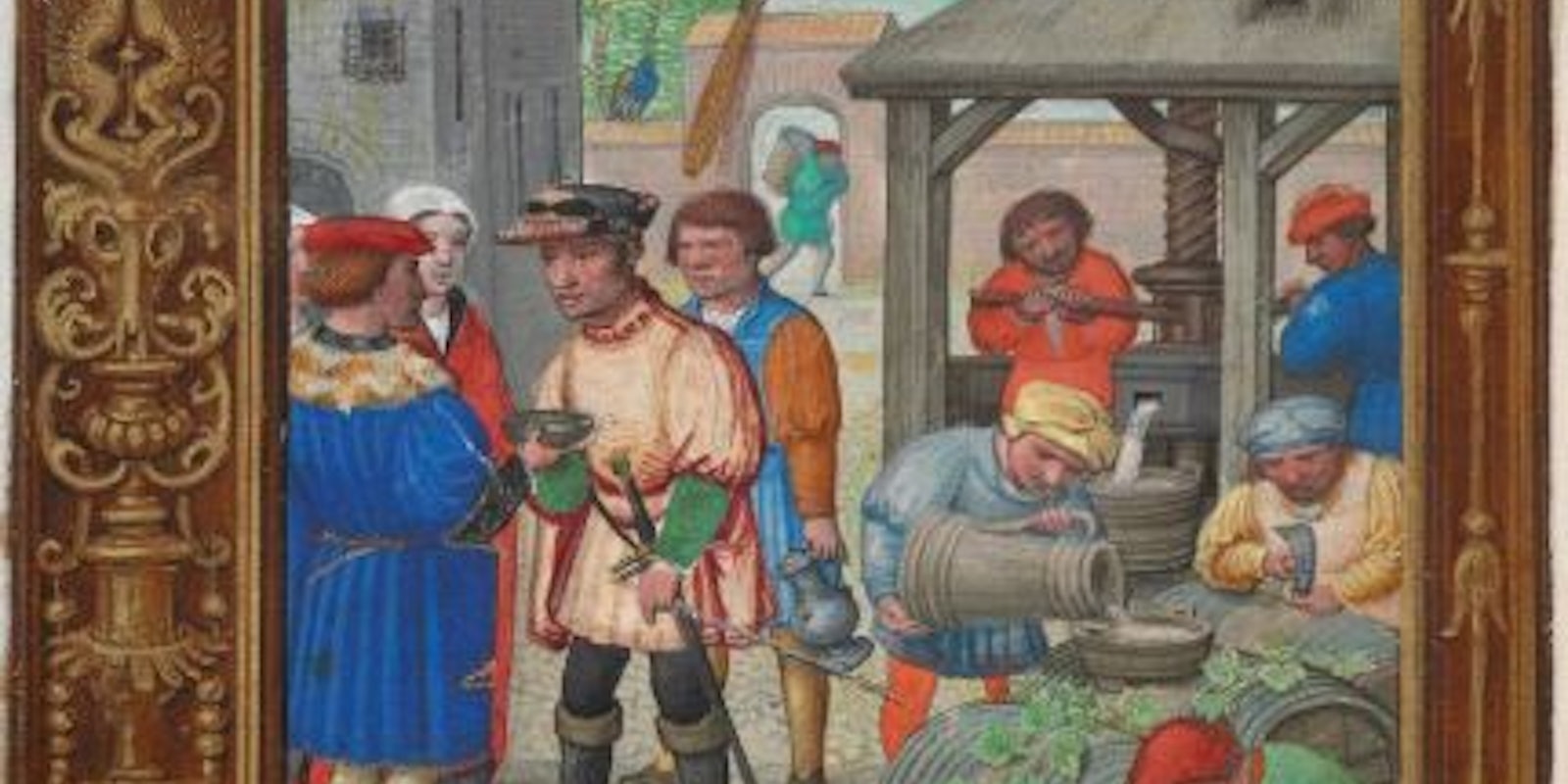

Each of these manuscripts is important to the history of our collective intellectual, artistic, and spiritual journey. But many are also extraordinary beautiful. The Golf Book, for instance, got its title for its series of miniatures depicting a game that looks a lot like today’s golf, painted by the great Flemish artist Simon Bening.

The Silos Apocalypse, a commentary on the end-times by Spanish monks in the 12th century, has almost graphic illustrations that have a remarkably numinous three-dimensionality that lends itself to simple slack-jawed staring.

Depending on your predilection, one manuscript or another may prove to be your favorite. Geeks may focus on the detailed mapping of the dynamic physical world in Leonardo’s crazy-backward-alphabet-land notebooks. Lovers of art have a number of choices.

But the tale tangled in the very threads of the Beowulf manuscript gives it special resonance for storytellers. The smudges might be the thumbprint of a lord come in from checking on his lands and relaxing with a beer and a book, or of a monk patching a tear or of a poet trying to winkle out the magic of this transportive, inelegantly proportioned work. But really, every mark, every stain and every burn (the manuscript was caught and partially burnt in the early 18th century) gives form to the story analogously to the way the story gives form to the modern imagination.

Of particular note when it comes to the British Library Digitised Manuscript project is the quality of the scans. They are the gold standard of online digitization. The colors are true and the zoom is such that you can see in some manuscripts the very grain of the paper.

There are many digital humanities proponents and tech specialists who can speak at length to the influence and implications of democratizing scholarly material. But most of you are not academics or particularly concerned with the politics of learning. Most of you are men and women with your own passions, those fiery paths that make living your lives more enjoyable, even thrilling. Thanks to the British Library, you will probably find something in this project that will fan those flames. “That which is equal to its period and place,” as the American poet Walt Whitman said, “is equal to any.”

Detail from the first line of “Beowulf,” “Listen!”

Images from the British Library’s Digitalised Manuscripts