Warren Kinsella’s conspicuously deleted blog post calling for Anonymous to get involved in the Rehtaeh Parsons case, as they had done in Steubenville, came mere days after my husband, Owen, and I returned to Ontario from a six-month stay in Mexico.

We were both suffering from serious culture shock (not to mention a wicked flu virus) and Parsons’ story hit me hard. Rehtaeh Parsons was a 17-year-old Canadian high school student who took her own life after a photo of her reportedly being gang raped was circulated by the alleged assailants. It felt personal, like a “welcome back, everything sucks” slap in the face.

We had lived in Parsons’ hometown of Cole Harbour, Nova Scotia, for several months before heading South, and I wanted desperately to help any way we could. We even talked about planning a trip East to assist with protest planning and independent media coverage.

In his efforts to begin organizing, Owen made contact with a woman claiming to be part of the Anonymous Canada group who was attempting to expose the young men alleged to have raped and bullied Rehtaeh Parsons. Their plan, at the time, was to discover the names of all the (mostly underage) people involved and use these names as collateral, a bargaining chip to convince authorities and politicians to take note and take action.

Owen and his source began sharing information, collaborating on stories, and working toward our common goals. We wrote about the story, sometimes critiquing Anonymous, and always trying to make a difference that would bring resolution to Rehtaeh Parsons’s loved ones. The source began sharing our notes and ideas with the group, a small collection of international hackers and activists with passions similar, it seemed, to mine.

This was my first foray into any kind of reporting and our first news story for the site. We were watching our traffic carefully to see who was listening, how we could speak to even more people, make Parsons’s story spread further, and have a greater impact.

One day, we noticed a strange link in our incoming referrals, a link to the titan pad, a collaborative document creation service often used by Anonymous for their projects. One click was all it took to bring on the wrath of the self-proclaimed anti-bullying group.

Suddenly we had access to every piece of information that Anonymous had collected—names, social media profiles, family members, occupations, and affiliations, even confessions.

Not trying to step on any toes, we immediately introduced ourselves and let them know that we had no intention of using any of the information we had stumbled upon unless asked to do so. We offered again to help and were quickly dismissed: “PLEASE leave the pad—it’s messing with the work performance.”

These were the words that launched a month of harassment from a group of Anonymous individuals actively engaged in an anti-bullying campaign.

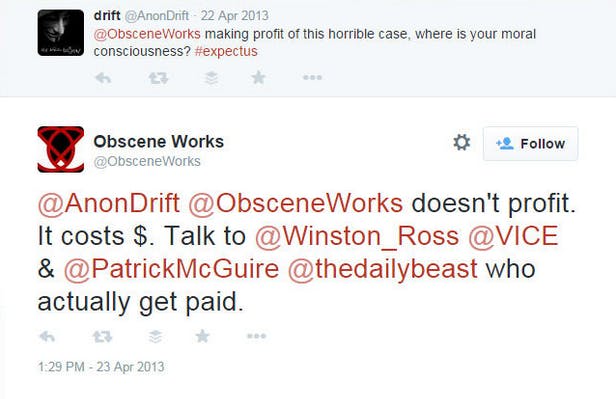

After this, Owen’s source asserted that all previous discussions were to be considered “off the record.” Within a few days, as we tried unsuccessfully to contact the group, we began to receive tweets and emails questioning our motives for writing about the story. Someone sent me a link to a “press release” titled “Journalists threaten anonymous,” which falsely claimed we had released information from the investigation to the public, had agreed to speak off the record and then broken this agreement, and that we were using the story to make money.

Then they “doxed” us. Or at least they tried to make it appear that they had.

As punishment for our unwitting infringement into Anonymous’s space, they released all the details they could be bothered to find. Namely, links to our public social media accounts, my website WHOIS details, and any old addresses and phone numbers they could come up with from the phone book. (None of them, thankfully, were places we still lived or numbers we still used.)

They published photos of both of us. They listed my weight from eight years before (“around 300 lbs—damn”), but of course, they didn’t say anything about my husband’s body. And then they labeled the whole document “Owen Ferguson and Rebecca the Cow.”

Yeah, it felt pretty terrible.

But the worst part of the entire situation wasn’t the immediate effects of being fat-shamed by strangers on the Internet or waking up to threats against my grandmother.

Because somewhere in the middle of it all, my husband and I lost track of why we had started working together.

He stopped sleeping at night, crawling into bed in the early hours of the morning in the pre-dawn light after spending hours trolling the trolls, a sure sign he was heading into a manic phase characteristic of his bipolar disorder.

We both let the paranoia of being targeted by Anonymous get to us, sending us down a path of extreme hyper-vigilance in our website maintenance. One day I came back from a short walk to try and calm myself, only to find that he had changed my email password. He doesn’t remember doing it, but at the time, he said he wanted to prove to me that my personal security was lax—as if someone from Anonymous was going to waltz into our shack of a house and hack my email by logging into it from my personal computer.

The animosity between us grew more uncomfortable, along with his symptoms. Our arguments became circular, accusatory. He felt like I had usurped his space by taking up blogging on a site he considered his alone. I felt like he was making us both look ridiculous with his confused, manic prose.

“You’re not a journalist,” he shouted at me one afternoon after I criticized his latest post. “You didn’t go to journalism school, I did!” A school he was forced to leave, I pointed out, a low blow even for me, sarcastic and cutting.

It wasn’t the first time that a wall of competition had grown between us. In a manic episode two years before, he had berated me for being a “terrible writer” during a fit of jealousy over my income, after I asked him to help edit a project I had left until past deadline.

I gave up. I recused myself from the Obscene Works website, reassigned my stories over to the publisher account, and left. Not just the website, but our home. I loaded all my things into the trunk of my car, and for two weeks, I cried into a pillow on a lumpy mattress at my parents’ house, sobbing and screaming into the phone, trying to convince him to get help that I obviously couldn’t give.

Even though our local mental health facility told him there was a six-month waiting list to see a doctor, it only took him a couple weeks to finally get treatment from a family physician. I came home.

And as his anger and mania subsided, so did the story. The government made conciliations to the Anonymous demands. The police committed to the investigation, and when charges were finally filed, a publication ban was ordered and the media went silent. Rehtaeh Parsons and everyone who had worked so hard to defend her faded into obscurity while we waited for some kind of resolution.

More than a year later, I reclaimed the stories I had written, able to look back on the time as tumultuous but productive, knowing that even if my actions did nothing to bring Rehtaeh Parsons’s attackers to justice, they solidified in me a passion for activism and advocacy on behalf of assault survivors. News organizations finally published her name again, ignoring the ban and sharing Parsons’ story in protest of a trial without justice.

I rarely think about the near-peril we found ourselves in with a collection of “hacktivists” who cared so much about enacting anti-bullying laws that they were willing to bully us to get them.

And I know that I’m lucky. The treatment I received is mild compared to the vitriol targeted at most of the feminist bloggers I know. And it’s nothing compared to what Rehtaeh Parsons herself went through, and what other rape victims are going through right now. As I write this, 4chan trolls are working to determine how they can do maximum damage to Jackie, the rape victim outed after the Rolling Stone UVA story scandal.

It’s been easy for me to forget the cruelty of strangers.

But I’m not sure I’ll ever forget my husband’s words, telling me that I’m not a “real journalist,” and not even a good writer. I can’t forget it, even though I know his support for my work is otherwise unfaltering. It sticks like a tiny voice in the back of my head, a reminder that sometimes even our greatest allies can cut us deeply.

I can’t forget it. But it doesn’t stop me. And because of this, I have the courage to keep going, to face the inevitability of a world where women who have a voice might never be safe to express it.

Being a writer, being a wife, being an activist—these things aren’t individual roles that I can turn off and on at will. They make up the whole of me. I can’t be one without the others. And not even the harshest criticism from the people I love most in the world can change that. For that reminder, at least, I am thankful.

Photo via sklathill/Flickr (CC BY SA 2.0) | Remix by Fernando Alfonso III