BY DENNIS OVERBYE

On Aug. 25, 1989, the Voyager 2 spacecraft slipped over the north pole of Neptune, then the most distant planet in the solar system, swerved south at Neptune’s big moon Triton and left the known worlds forever.

Today Voyager 2 is 10 billion miles from the Sun and bumping through the magnetic frontier between the solar system and interstellar space, but planetary scientists are still poring over the data from its last planetfall, at Triton, for clues to what they might expect the next time humanity encounters a new world. That will happen July 14 next year when the New Horizons probe goes past Pluto and its icy moons, of which five are currently known. Pluto, of course, was once upon a time the smallest and most distant planet in the solar system, and the only one that has never been visited.

It turns out, however, that Pluto and Triton are probably long-lost brothers. And so at the end of Voyager’s 12-year-long cosmic picture show, scientists might have seen a preview of coming attractions.

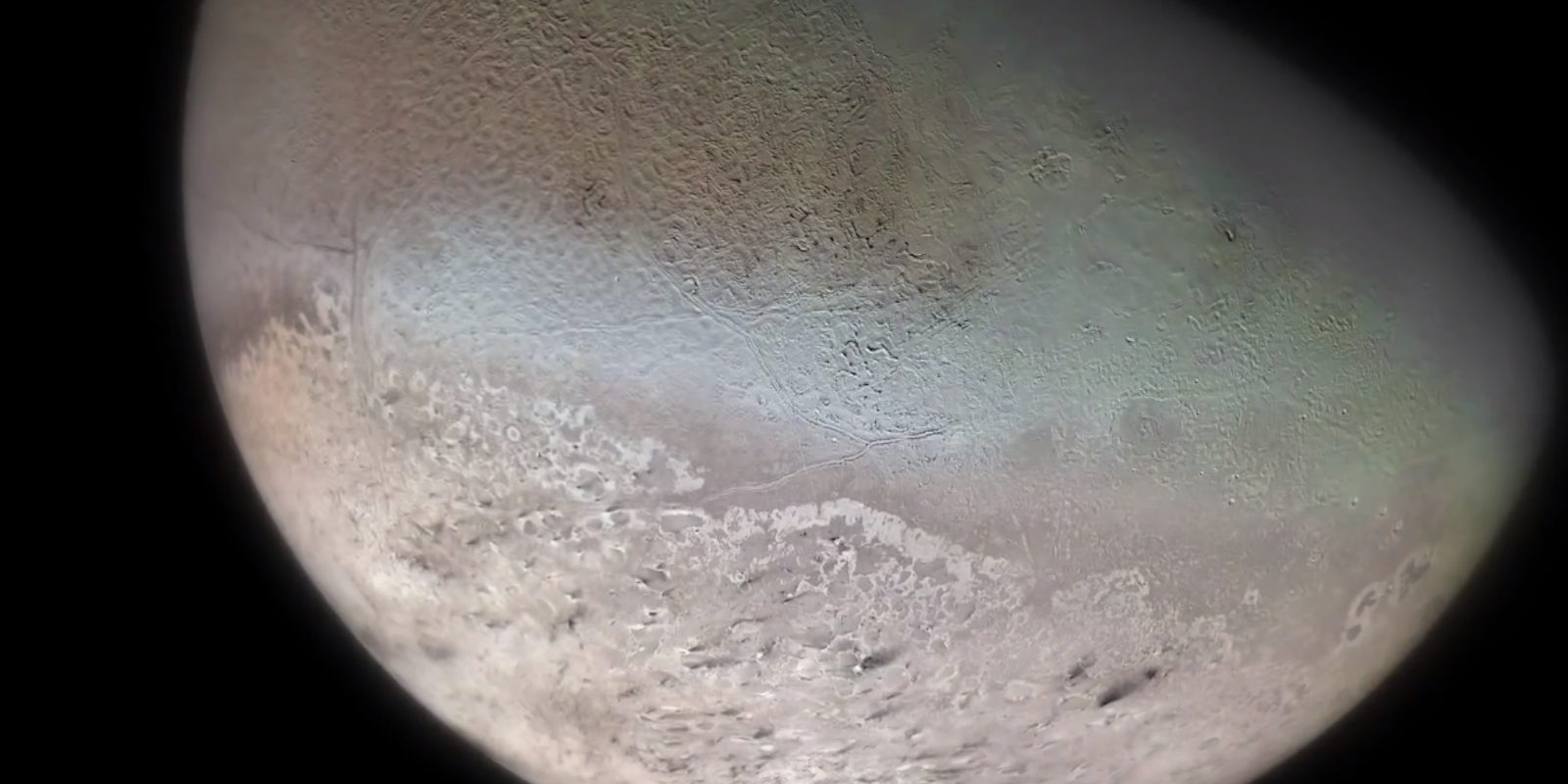

Triton, Neptune’s largest moon and one of the largest in the solar system, is the only one that goes around its planet backward, in the opposite direction of Neptune’s rotation – retrograde, in astronomical lingo. Which means it couldn’t have formed out of the swirling blob of gas and dust from which Neptune presumably condensed back at the dawn of the solar system.

Astronomers have concluded, therefore, that Triton is a stranger from outside Neptune’s system; the moon was kidnapped, they theorize, from the Kuiper Belt, a vast ring of icy debris left over from the formation of the solar system.

Read more in the New York Times.

Screengrab via NewYorkTimes/YouTube